Ayodhya Case Falsely Projected as Hindu-Muslim Conflict: Hilal Ahmed

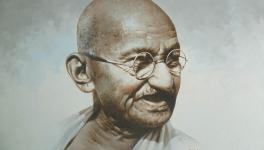

Hilal Ahmed

Hilal Ahmed, associate professor, Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, is an expert on Muslim identity formation and the politics of symbols in South Asia. In an interview with Newsclick, he explains how the Ayodhya dispute fostered a Hindu-Muslim binary. He suggests an alternative mode to address Muslim anxieties in contemporary India. This would involve evaluating memory-based faith on moral, not historical, grounds, through a “radical politics of peace and social harmony”.

In your recent book, Siyasi Muslims: A story of Political Islam in India, you talk about caste among Muslims. Do you think that the Ayodhya issue helps transcend the caste or class differentiation among Muslims today, maybe even temporarily?

This is a very valuable question, which requires some elaboration. Muslims are certainly divided on caste, region, language and class lines. Yet, there is a sense of oneness, which determines their imagination of Islam and Muslims, at least in two different ways.

In a positive sense, Muslims of India become a homogeneous legally-recognised entity when individuals with Muslim names and/or groups, who prefer to call themselves Islamic, are recognised as beneficiaries of constitutionally-granted collective rights, such as the right to profess religion and the right to protect culture and heritage.

However, Muslim oneness is also defined in a negative sense when they become a targeted political community. When individuals with Muslim names or when legally-recognised minority institutions with Islamic contents are threatened and violently attacked by Hindutva essentialists. These conflicting meanings of Muslim homogeneity actually constitute two dominant political perspectives of our time: the legal-constitutionalist liberal perspective and the Hindu nationalist perspective.

Liberal constitutionalists defend Muslims by invoking minority rights; while Hindu nationalists reject the minority-majority framework and call it Muslim appeasement. However, if we closely look at the nature of their arguments, we may find a remarkable similarity. Both envisage Muslims as an identifiable community that is comparable with another collectivity called the Hindus.

This construction of Hindu-Muslim binary, in my view, is empirically weak, sociologically untenable and politically disastrous. Therefore, the important question you ask must not necessarily be situated in the Hindu assertion versus Muslim reaction framework.

Instead, I suggest an alternative mode to address Muslim anxieties in contemporary India. The crucial distinction between Muslim communities we know empirically and the Muslims we imagine as pan-Islamic community is very important. Interactions with Muslim individuals in concentre everyday life situations are always treated as normal. No one, not even the hardcore Hindutva activists consider such interactions an extraordinary experience. But, whenever we are forced to think about a few contentious all-India level issues—population growth, war with Pakistan, international terrorism, and electoral behaviour of Muslims and so on—we tend to rely on the given picture of Muslim community as a homogeneous, fixed, rigid, anti-modern group.

To get rid of this problem, I argue that we must make tentative, open-ended and context-specific arguments. This is exactly what I do in my work.

But what is the significance of the Babri Masjid for Muslims; would the issue mean they give up caste/class considerations?

One clarification is needed here. The supposedly ‘neutral expressions’ to address the Babri masjid as disputed structure or the Ayodhya crisis are one-sided. It is not possible to establish that a temple was demolished by Babar for purely religious reasons. Archaeological excavations (as the court has decided to treat the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) report of 2003 as scientific evidence in this case!) cannot determine the intention and actions of historical figures or communities.

On the contrary, however, we have concrete evidences that demonstrate that the Babri Masjid was demolished by the Hindutva forces in the name of religion on December 16, 992. Thus, the Ayodhya dispute is primarily about the Babri masjid; the Ram temple is an associated phenomenon. This centrality of the mosque in this case actually gives us an impression that Muslims of all kinds are deeply concerned about it. But, this perception is not entirely correct.

My first book, Muslim Political Discourse in Postcolonial India: Monuments, Memory and Contestation (2014), examines the nature of Babri masjid conflict and its emergence as a Muslim issue. I find that the Babri masjid issue—which was a highly-localised conflict since 1949—was imposed on Indian Muslims by Hindu and Muslim fundamentalists in the post-1986 period.

The Muslim elites gave it up in 1991 when their two main demands—an Act of Parliament to protect the religious places of worship and the transfer of the title suit to a special bench of the high court—were accepted. Interestingly, Hindutva politics also achieved what it always desired: a functional temple at the site and control over the court case. The temple is still there and the Vishwa Hindu Parishad [or VHP, a militant offshoot of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh] supported Ram Lalla Virjman as a party in the title suit.

So, it was a win-win situation for both Hindu and Muslim elite. However, Hindutva politics wanted to use this episode for its wider Hindu Rashtra-oriented politics. That was the reason why the VHP came out with an interesting proposal: the construction of a grand Ram temple in the post-demolition period.

Againt this backdrop, I do not think that Muslim communities would become a homogeneous entity even if the title suit is decided in favour of two contending anti-mosque parties in this case: the Ram Lalla Virajman and Nirmohi Akhara.

The Bharatiya Janata Party has been ‘othering’ Muslims in a concerted way. After 2014 came a spate of lynchings, the National Register of Citizens in Assam, then Kashmir, and now comes Babri (though it is coming via a Supreme Court case). What do these mean for Muslims in India today? Accordingly, what do think Muslims expect from the judge in the Ayodhya case?

Let me address the Babri Masjid issue first: I argue that Muslims do not have any interest in the Babri Masjid case for two obvious reasons. First, the mosque or at least its structure, was demolished in 1992, hence, there is no mosque on the disputed land. On the other hand, there is a functional Hindu temple, which is open to all Hindus.

A Hindu can visit this temple, offer bhog to the deity and commemorate lord Ram’s birthplace on the site where the Babri Masjid once stood. However, this is not the case with Muslims. A Muslim is not allowed to offer prayer on this land. This legal restriction discourages the Muslims to assert their religious claim on this site for regular namaz etc, as the Babri Masjid does not have any special religious status for Muslim communities. The Babri Masjid becomes an irrelevant mosque for Muslims, especially after its demolition in 1992.

The second reason is related to the nature of Muslim politics of Babri Masjid. All Muslim parties and groups decided to recognise the AIMPLB’s High Power Committee as the core body to look after the legal case on Babri masjid after its demolition. The Babri Masjid Action Committee passed a resolution on December 1, 1993 to suspend all the agitational programmes and activities.

The common Muslims, who were mobilised in the name of protecting the mosque, were always told that Babri Masjid was a political defeat for them. Even the legal achievements—the 1991 Act and the High Court verdict of 2010 that recognises the stake of the Sunni Waqf Board—were never celebrated by the Muslim elite, simply to keep the issue alive.

Thus, religious irrelevance of Babri Masjid and political betrayal of Muslim elite do not allow Muslim communities to get associated with the Babri Masjid case at all.

You say Muslims do not have any interest in Babri Masjid, yet after the demolition there was violence across the sub-continent; in Bangladesh, Pakistan and India. Did the sense that sacredness had been violated not contribute to the violence? Also, there are ASI-protected mosques where prayers are not held, but that cannot be invoked to turn them into temples?

Demolition of the Babri Masjid certainly had a psychological impact on Muslims of India. But it did not provoke them for violent reactionary politics of any kind. The violence that took place after December 6, 1992 event cannot be described as Muslim reaction. In most of the cases, Muslim neighbourhoods were attacked by Right wing Hindu groups. There are various studies, including judicial inquiry reports, which suggest that post 1992 riots in India were primarily anti Muslim in nature.

But it does not mean that we do not make any distinction between common Muslims and underworld criminals who happen to be Muslims. The Bombay blasts case actually demonstrates this fact. The underworld rivalries found a new communal overtone and eventually the criminals started acting as representatives of Hindu and Muslim interests.

The riots and attacks on temples in neighbouring countries were primarily anti-minority in nature. We must remember that religious minorities in Bangladesh and Pakistan are often prosecuted because officially these states are the outcome of the two-nation theory.

I have written extensively on Muslim politics with regard to the ASI protected mosques, where namaz is not allowed. These mosques have always been communally sensitive for obvious technical reasons. The 1958 Act [Monuments and Archaeological Sites and Remains Act] determines the status of a building on the basis of the date when ASI declares it as a protected monument. If the building is not used for any religious activity on the date of notification, it will be treated as non-functional monument. This law is problematic as it contradicts with the Wakf laws and the right to religious freedom.

Muslim politics of the 1980s revolves around these issues and Babri Masjid actually merged into this right to heritage debate. The Protection of the Religious Places of Worship Act 1991 was passed in the backdrop of it. Although the Act did not respond to the ASI law [the 1958 Act], it provided a legal definition to historic mosques.

As a result, all the possibilities to convert any mosque into a temple on the basis of “faith” died down. The Hindutva forces also decided to concentrate on Ayodhya and stopped talking about Mathura and Kashi!

However, in the present circumstances, the possibility of a rejuvenated Hindutva politics on ASI protected mosques cannot be ruled out.

And, the question of what is the Muslim perception of the anti-Muslim discourse?

Here it is important to note that Muslim political responses are often understood only with regard to at a few identity-based issues: Urdu, the minority status of Aligarh Muslim University, personal law/shariat and even Babri Masjid. This narrowly-defined imagination of Muslim attitude is nurtured, protected and reproduced by political parties.

The so-called secular parties and Muslim political elites who claim to represent Muslims exaggerate this identity-based victimhood. Even the Sachar Commission Report, which factually demonstrates Muslim backwardness, has been presented as a symbol of political victimhood.

On the contrary, the BJP uses the Muslim identity as an “other” to cultivate its Hindutva vote bank. Unlike the previous National Democratic Alliance (NDA) government, the Modi-led BJP deliberately and directly demolishes “Muslim issues”.

This negative portrayal of Muslims presence certainly contributed to what may be called Hindu polarisation. Various studies demonstrate that the consolidation of Hindu political identity emerged as a decisive factor in post-2014 India. However, this Hindu polarisation could not produce any collective Muslim reaction. Issues like ‘love jihad’, ghar wapsi, Ram temple, and even the ban on triple talaq could not provoke Muslims to respond to the BJP’s Hindutva-driven discourse more directly.

This strategic failure forced the Hindutva groups to focus entirely on the aggressive politics of cow protection, which eventually led to a new form of anti-Muslim violence: mob lynching. Unlike a full-scale riot, lynching was more economical. In this case, Muslim individuals were to be targeted to create a powerful impact.

Mob lynching has been the most impactful and demonstrative political technique so far that has certainly affected the Muslim communities across India. Yet, it has not acquired a political vibrancy as a Muslim issue. Although the Congress election manifesto of 2019 does talks about a law to control mob lynching, the non-BJP parties have not articulated it as a politically useable agenda for electoral mobilisation.

The adverse depiction of Muslim presence in public life (as well as the new form of violence against Muslims), I suggest, have repositioned the Muslims as an identifiable anti-national community—the “other”. Yet, this otherness has not produced any electorally-sustainable binary between Hindutva-driven politics of the BJP and its opponents.

There is a general belief that the Ayodhya judgment would go against the Muslim side. What does this expectation tell us about our society, our political system and judiciary?

Let me elaborate the nature of the legal conflict in this case. The Ayodhya case that the Supreme Court is hearing is being falsely and simplistically projected as a Hindu-Muslim conflict. It is not. It is a typical property dispute in which land, a built structure, and the possession of land are being fought over by three parties.

Each of the three parties—the Sunni Wakf Board, the Nirmohi Akhara and the Ram Lalla Virajman—have fought the case on very distinct arguments of law, memory and faith. The VHP-supported Ram Lalla Virajman makes a faith-based argument that Hindus believe in the unquestionable divinity of Lord Ram and that the court must respect the sentiments of the Hindu community.

The Nirmohi Akhara relies on the memory of the conflict to argue that it has an ultimate right over the land. And the Uttar Pradesh Sunni Wakf Board evokes the centrality of law to make a case for the land (not the mosque). We must remember that the Nirmohi Akhara challenges the VHP’s grand Hindu politics on two counts. First, it opposes the VHP’s claims on historical grounds, arguing that it has been the main contender since 1934.

Second, it also turns down the Hindu nationalist project of the Ram Lalla Virajman by highlighting the localised nature of the conflict.

It is clear that each party identifies its own comfort zone and makes conscious efforts to redefine the ownership of land into a conflict of civilisations between Hinduism and Islam. The courtroom, in this schema, has been transformed into a theatre, where different narratives of conflict are enacted in a way to sustain the conflict.

Hindus and Muslims of this country have not given any mandate to these organisations/individuals to speak on their behalf. Nor do they represent the authoritative versions of Islam and Hinduism. Yes, the Ayodhya dispute needs to be solved; but the framework of solution must respond to the anxieties of those Hindus and Muslims, who live together peacefully as citizens.

You mentioned memory and history. Memory is not static but gets constantly reinvented. For instance, we have no textual basis for believing with surety that there was a temple at the place where the Babri Masjid once stood. The so-called evidence for such a temple actually surfaced in the late 19th century. Therefore, what does one do to deal with memories of things that may never have been, but which have potential for causing tremendous tumult in present times?

Yes, memories are not static. Many a time, certain memories become part of our collective belief system. Babri Masjid, in this sense, symbolises a memory of conflict, which actually constitutes our common sense. This memory of conflict legitimises the historical conflicts between Hindus and Muslims to justify the contemporary idea of ‘Hindu victimhood’.

Collective memories of this kind should not be countered by producing hard core facts of history. The Historians Report on Babri Masjid (1991), which rejected the claims of a Ram temple on factual basis, was such an attempt. These professional historians were not at all wrong. They did a remarkable job. But their political judgment was problematic. They tried to question the memory/faith in Ram temple by producing historical facts. This gave an additional advantage to the Hindutva politics to concentrate more on the memory of conflict as faith in the existence of lord Ram.

Does this mean memory cannot be questioned?

It does not mean that this memory of conflict cannot be questioned at all. In my view, one needs to evaluate the memories-based faith of this kind on moral grounds. For instance, one must pose three basic questions:

-

Are Muslims and Hindu communities of India responsible for the acts and deeds of medieval rules?

-

Is it justifiable for a Hindu who follow lord Ram—the Maryada Puroshottam—to demolish a religious place for constructing a new temple?

-

Is it justifiable for a Muslim to offer namaz in a mosque that is not built on a legitimate land dedicated in the name of Allah?

These simplistic questions require a different kind of moral wisdom to refashion a positive and radical politics of peace and social harmony. The political parties involved in the competitive electoral politics cannot get into this kind of politics as they have to rely on electoral managements of groups and communities. The non-party political formations and peoples’ movements may be the answer.

Even archaeological theories are often contested as new layers are found beneath existing buildings. In the case of Babri Masjid, do we have a situation where the State is becoming an interested party, creating and manufacturing knowledge? For instance, archaeological research into Ayodhya that began in the first NDA term. And now we are even being told to “re-write” history at will. In this sense, what does the Babri Masjid symbolise today—for the Indian state, the Muslims and the Hindus?

Yes. The State is a party now. This process began in 1991 when the state invited the conflicting groups for what is called negotiations on Babri masjid. As I pointed out, the Supreme Court has indicated that the ASI report will be recognised as scientific evidence, while the Historians Reports of 1991 (that rules out the possibility of any Ram temple) may be treated merely as the opinion of a few politically-charged historians.

This legal interpretation of history as an opinion and archaeology as science to discover the final truth of the birthplace of Lord Ram is problematic. Professional archaeologists make inferences and opinions on the basis of the material/data they collect. After all, archaeological findings are subject to multiple interpretations. This is also true about various archaeological excavations in Ayodhya. The archaeologists excavated Ayodhya city on number of different occasions—not to search the exact location of lord Ram’s birthplace—but to practice what they call “tradition-based archaeology”.

No one knows what will happen to the title suit. But it is certainly clear that the purpose of archaeology is completely defeated in the Ayodhya case. It is not possible now to search the archaeological universe in which the story of Lord Ram was composed—primarily because everything related to this tragic figure has been converted into a rigid faith and orthodox science.

We must remember that professional archaeology is always concerned about the future’s past. It makes tentative moves to suggest that our understanding of the past is momentary; therefore, we must not make it rigid and fixed. The proposed Hindutva project to rewriting the history is basically an extension of the memory of conflict, which must be questioned on two counts: the professionalism of history and radical politics of peace and social harmony.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.