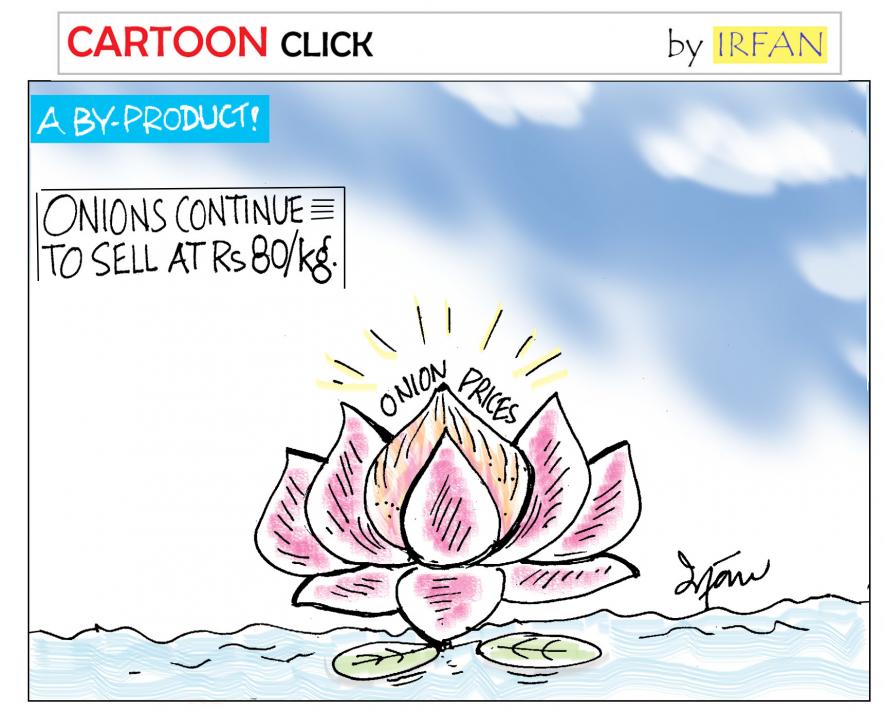

Why Onions Make Govts Cry and What Can Be Done About it

Onion is one of the many prominent success stories of Indian agriculture in the last decade. And yet, excessive rains in Karnataka, Maharashtra and Madhya Pradesh, which produce about 60% of India’s onion, have caused disruption of supplies, causing its retail prices to touch Rs 80 per kilo in Delhi and Mumbai.

After the launch of the National Horticulture Mission (NHM) by the United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government in 2004-05, several state governments promoted cultivation of onion by taking advantage of the incentives offered by the Central government. As a result, the area under onion cultivation increased from 7.5 lakh hectare in 2009-10 to 12.70 lakh hectare in 2016-17.

Accordingly, onion production increased from 12.1 million tonnes to 21.5 million tonnes, an increase of about 78%. In 2009-10, Madhya Pradesh (MP) produced 9.5 lakh tonnes of onion. By 2016-17, the production increased to 3.2 million tonnes. In this period, the productivity of onion stagnated in the major producing states of Maharashtra and Karnataka, but in MP, the productivity went up from 16.6 tonnes per hectare to 27 tonnes per hectare. Nevertheless, average productivity of India (about 17 tonnes per hectare) is about one-third of the United States.

By 2016-17, India produced 21.5 million tonnes of onion while the estimated demand was 20.8 million tonnes. India was meeting not only the domestic demand of onion but was also able to export onion to other countries.

Despite this success in increasing production, onion continues to bring tears to governments, especially if they are facing elections. The price of onion remained depressed from 2016 to 2019 and it was only in the last six months that there has been an increase in prices.

Nashik in Maharashtra is the highest producer of onion in India. In 2015-16, it produced 1.24 million tonnes of onion, about 6% of India’s production. The wholesale price at Nashik sets the trend of onion prices across India. On September 23, it touched Rs 4,000 per quintal and created a panic-like situation in TV studios.

It was forgotten that only about two years ago, in 2017, farmers in Madhya Pradesh were forced to sell their onion at Rs 200 per quintal, as there were no buyers. Ultimately, the state government purchased 8.76 lakh tonnes of onion from farmers at Rs 800 per quintal. Due to high perishability and prospects of huge losses, onion had to be sold at almost one-fifth of the cost and the state exchequer incurred a loss of about Rs 785 crore.

The lesson from this: Governments are ill-equipped to purchase and sell large quantities of perishable commodities.

This is certainly not the first time that onion prices are in the headlines. Faced with a similar situation of rising prices of onion, the Competition Commission of India (CCI) studied the matter and submitted a report in October 2012.

CCI had found that price discovery in the APMCs (Agriculture Produce Marketing Committees) is opaque and farmers consider only the prices in mandis (wholesale markets) around them while traders take into account the onion prices in distant markets as well as export destinations. Due to entry barriers for new traders in the mandis, the farmers have limited options to sell. The commission agents favoured the wholesale traders rather than the farmers. Secret bidding in mandis was found to be common.

It is a tragedy that we are in 2019 but onion trade is still beset with the same problems as the CCI identified exactly seven years ago. Meaningful reforms of APMCs are yet to be taken up and very few new licenses have been given to commission agents and wholesale traders in mandis. Private mandis are still to take off (except in Maharashtra) and at the ground level. It was envisaged that e-NAM [a national online agricultural market launched in 2016] will bring transparency to mandi operations, but the Centre did not push states hard enough to implement it in its real spirit and in the major mandis of India, e-NAM has made little difference.

Storage of onion is still waiting for a technological breakthrough. Potato and apple can be stored in cold-chain conditions for six to eight months. Onion of Rabi crop is stored in hessian bags in ventilated structures, without any temperature and humidity control. Under the NHM, which has now been renamed as the Mission for Integrated Development of Horticulture or MIDH, the central government has been giving subsidies to farmers to construct low-cost thatched bamboo storage.

During the monsoon months, losses in such storage can reach about 30%. By 2016, 8 lakh tonnes of such storage capacity had been created by farmers. The state had plans to add another 4.3 lakh tonnes of onion storage by March 2019. It is not known how much of additional capacity has actually been created in the state. But the assumption that all the farmers sell off their onion immediately after harvesting and that it is only the traders who hold the stocks and benefit from higher prices, is not correct. The farmers who store onion also gain from higher prices in the market and they do suffer from government’s ad hoc decisions to check any rise in its prices.

Faced with a similar situation, previous governments also took the easy route of imposing stock limits, fixing high Minimum Export Prices (MEP) or banning exports (as was done in December 2010 and September 2011). In December 2013, MEP was $1,150. By March 2014, it was brought down to zero. In August 2015, the MEP was once again raised to $700, to be reduced to zero by December 2015. In 2015-16, onion traders faced income tax inquiries and even police investigations. Since then, onion prices have remained very low and in many months in 2016 to 2018, they were lower than their cost of cultivation of about Rs600 per quintal.

In a prudent decision, in 2015-16, the Narendra Modi government 1.0 operationalised a Price Stabilisation Fund for purchasing an agricultural commodity at market prices (not necessarily at the Minimum Support Price or MSP) and releasing the same in the market in case of price rise, so as to cool the market. While it is not possible for the government to build a massive stock of perishable commodities, their mere presence in markets has the effect of checking the tendency to hoard.

This year also, Nafed, the apex body of agri-marketing cooperatives, purchased about 56,000 tonnes of onion which can be sold in big cities to cool its prices. When onion of the Kharif crop starts arriving in the market—in the next three weeks—its retail prices are likely to fall.

Finally, the government should undertake a campaign to popularise the consumption of processed onion, as was done by National Egg Coordination Committee in the 1980s. Purchase of onion by food processing industries will reduce volatility in prices as well.

A long-term solution to the volatility in onion prices lies not in the knee-jerk reaction of imposing ad hoc stock limits, MEP, bans on exports and action under the Essential Commodities Act. Rather, the solution lies in forcing states to implement real reforms in mandis, development of better storage technology and investment in storage at major consumption centres.

Siraj Hussain was Secretary, Ministry of Food Processing Industries and Ministry of Agriculture, Cooperation and Farmers Welfare. At present, he is Visiting Senior Fellow, ICRIER. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.