Assam's Battle for Dispur: And What of the 'Real Issues'?

GUWAHATI: One phase of the Assam assembly elections is over and a high voter turnout was recorded – as is usual in Assam these past decades. A fortnight down the road, the rest of the state – especially Western Assam with substantial Bodo and Muslim populations will be voting.

The election has transformed into a no holds battle for both the Congress and the Bharatiya Janata Party and their respective allies. The former is battling a significant anti-incumbency factor and the BJP is trying to cash in on the need for a change with its younger leadership, catchy slogans and Narendra Modi’s appeal.

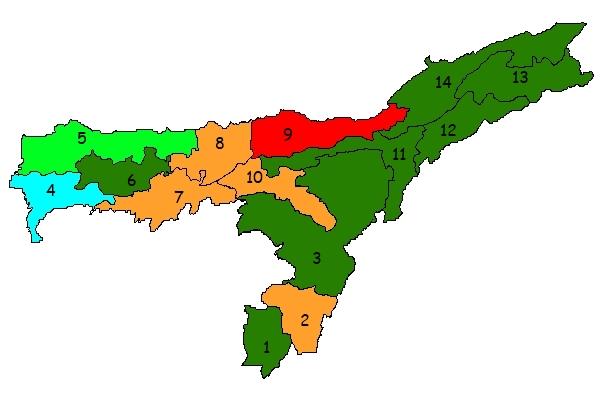

Image Courtesy: en.wikipedia.org

Yet, amid the dust and din, it is interesting to note the diminishing of an earlier factor: in the past, demands for a boycott by one major insurgent group or the other, whether the United Liberation Front of Asom (ULFA) or the National Democratic Front of Bodoland (NDFB) for the main and smaller groups in Karbi Anglong and North Cachar (Dima Hasao) districts.

Today, these voices no longer carry weight (in fact, whenever such boycotts were announced, people would come out to vote with a vengeance to oppose such anti-democratic stands) except in some pockets. That in itself represents an extraordinary change in the state in Chief Minister Tarun Gogoi’s time – it cannot be forgotten that during his initial years, ULFA and the NDFB were extremely powerful entities. Bomb blasts and attacks were commonplace. Fear kept people indoors after dark; poor infrastructure and communications did not help either in dealing with the concerns of insecurity. The explosions of 2006 which killed of over 200 people in Guwahati and other towns and which were blamed on the NDFB are still strong in public memory.

Gogoi used to say that when he came to power, the fear factor was such that not “even night shows were being screened in Guwahati”. Today, he points to the burst of energy and economic activities, new roads, multiplexes and malls, the signs of “growth” with the surge of people with disposable incomes, the visible purchase of properties, setting up of new businesses, the changing skyline of towns such as Guwahati. Peculiarly, he even saw economic growth in the growth of plastic trash and traffic jams.

Those experiences of past violence and boycotts appear to be a thing of the past and distant as if they were a strange and painful nightmare. The people have voted with the understanding that it is important to do so at a time of complex pressures and counter-currents.

Vikas may not have been surging in Assam but the basis for that is peace and stability: the state government in collaboration with the Centre and then Governments of Bhutan and Bangladesh did a huge amount in the past decade especially to defang the seemingly all-powerful armed groups. Public fatigue and opposition to the armed factions also has grown for the latter appear to have lost their ration d’etre. This is art of the public record and cannot be denied.

Although ULFA continues to exist, it has split into two groups in the typical style of rebel organizations which are more than 20 years old in this region and the way Governmental agencies divide and rule: typically, one group would be a pro-talks faction (after having either surrendered or captured) and an anti-talks faction based for the most outside the country – these are now located in western Myanmar under the benevolent eye of SS Khaplang, the elusive chairman of the National Socialist Council of Nagalim faction which bears his imprimatur. The Assamese anti-talkers are with Khaplang; that’s Paresh Baruah and his group.

Yet, even the ULFA faction is not demanding anything extraordinary but a constitutional demand which shows how far from its original position this group has come – it wants ST status to be given to six groups, including the Mataks, Baruah’s own ethnic community.

But how significant is the issue of security to the voter is unclear. In several parts of the state as elsewhere in the region, health and education parameters are poor. Assam has India’s worst MMR (Material Mortality Ratio – the number of women dying in pregnancy is 300 per 100,00 deliveries). It is also the second worst Infant Mortality Ratio through both indicators have hugely improved since 2003-04.

There are three political factors at play here: the first is the incumbent stressing the need for stability (especially safety for Muslims and minorities), governance and “proven“ delivery. The second is an anti-incumbency factor with an appeal to younger people for change and development, the Modi pitch. The urban and youth vote are likely to go here as also a substantial chunk of the tea garden community. There’s a third factor, which we’ll examine later.

State BJP President Sarbananda Sonowal and former Gogoi aide turned bitter foe Himanta Biswa Sarma are leading the party’s battle for the future of Assam from the front. Sonowal is a former president of the influential All Assam Students Union and it was his plea which led to the Supreme Court overturning the Illegal Migrants by Determination Act. However, after calling for the expulsion of Bangladeshis from Assam – a term that is widely seen as meaning Muslims of Bengali origin, Sonowal now is saying that deportation would have to be discussed with Bangladesh. But that’s been a no go with Dhaka for a quarter century since the movement against migrants began in Assam. There’s no indication that this is likely to change.

A point to be stressed here: in the eyes of detractors, it doesn’t really matter when the ‘migrants’ came to Assam. Figures about population growth are bandied about and the surge in the Muslim numbers is attributed to immigration from Bangladesh. Few even pause to consider the fact that the growth rate over decades in some areas has been substantially higher than other parts of Assam because of high fertility rates.

Yet, this rhetoric and of those who claim this is the last battle to save Assam and drive out Bangladeshis is likely to backfire for two very simple reasons: how could you and where would you expel people to if the ‘recipient’ country declared that these were not its nationals? Suppose Dhaka further defined efforts at deportation as illegal and unacceptable in international law and amounted to an unfriendly act by a neighbour -- which has also fenced its borders?

More questions: Would the Centre and the party in power enjoy being the target of national and international human rights groups (the anger of such groups is in itself an acknowledgement of their sensitivity to accusations of hate speech and abuse). No government, whether at the Centre of the state, wishes to create new law and order problems for itself. The updating of the National Registrar of Citizens on the basis of documents going back to 1951 has been a mammoth and remarkable exercise in trying to locate the notion of citizenship as well as to close the citizenship versus illegal immigration debate. Hw many of such ‘illegals’ actually turn up through these lists will be known soon enough.

Muslims will remember the state Government’s failure to curb the 2012 riots in the Bodo Territorial Council areas where both Bodos and Muslims suffered, although there were vastly more Muslim victims. Brutal incidents also followed in 2014 and 2015 where Adivasis and Muslim women and children were killed.

This is where the Third Factor in Assam comes into play – the Ajmal factor. Perfume baron with a network of factories and stories across India and the Middle East, Badruddin Ajmal is an ambitious figure who sees himself not just as kingmaker but maybe, given Assam’s complex politics, as a possible king. He’s won more seats in every election since his fledgling party burst onto the political arena in 2001. He has a fiercely loyal Muslim vote which sees in him as a protector if not a savior. With supporters among other communities, including Hindus and STs, Ajmal will probably eat into both BJP and Congress votes as well of the Asom Gana Parishad which ruled Assam twice but is now a shadow of its former self.

(There’s the new Liberal Democratic Party of former BJP President Pradyut Bora which has little chance of winning any seat but could capture some middle-class votes.)

Given Assam’s consistently high turnout, it won’t be surprising if the contest between the two main players sees the seats largely divided between them. In the process, the AIUDF campaign to be the third critical force and Ajmal’s dreams may get squeezed out.

(Sanjoy Hazarika is honorary research professor at CPR and holds the Dr. Saifuddin Kitchlew Chair at Jamia Millia Islamia, New Delhi, where he also directs the Centre for North East Studies and Policy Research. He is a well known journalist and filmmaker from Assam)

Front Page Image Courtesy: pixabay.com

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are the author's personal views, and do not necessarily represent the views of Newsclick

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.