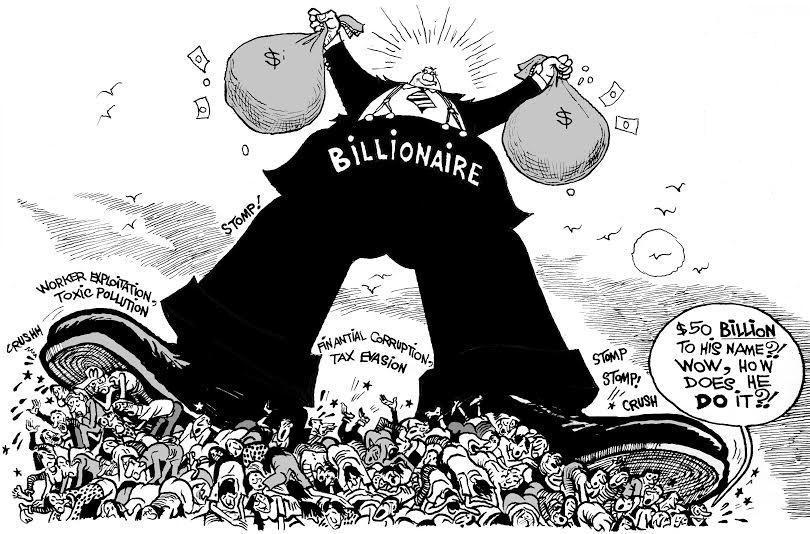

Just 2% of Top 500 Indian Companies Take Half of Total Profits

In financial year 2017-18, the top 10 companies swallowed up 45% of the total profits among the top 500 companies, according to an annual list recently released by the Economic Times. Back in 1993-94, the top 10 profit-making companies earned a third of the total profits of the largest 500 companies.

The report also pointed out the obvious fact that “the concentration of income has moved from government to private corporations” — as only three of the top 10 companies, ranked by profit, are now public sector undertakings (PSUs). In 1993-94, seven of the top 10 most profitable companies were PSUs.

The ET report attempts to explain this fact of massive disparity in company earnings and corporate concentration, speaking to analyst after analyst, one of whom calls this fact a “counter-intuitive finding”.

“Logically, with more competition, the concentration of wealth should have come down over the years,” says a financial analyst to Economic Times in the report accompanying the list.

Also Read: The Dramatic Rise in Wealth Inequality

But the fact is, this concentration is hardly “counter-intuitive” — given that corporate concentration is today the defining fact of business globally, even in advanced capitalist countries.

In the United States, for example, just 30 firms earned half of the total profits made by all publicly listed companies in the country in 2015. This number was 109 in 1975 and 89 in 1995. Meanwhile, the top 100 firms accounted for 84% share of the combined earnings of all listed companies. Again, this figure was 49 in 1975 and 53 in 1995.

Profit concentration in India’s corporate sector is similar.

Speaking to Newsclick, economist Surajit Mazumdar points out that this concentration shown in the ET data is only within the top 500 companies — so the disparity and concentration is vastly more when we account for all registered companies in India.

“The corporate sector consists of several thousands of companies, the number of total registered companies in India would now be close to nine or 10 lakh. And within that, a few hundreds account for the bulk of the profits in any case,” he says.

He says this disparity can be seen from the annual Union Budget documents, in the section on the revenues foregone where income tax returns of over six lakh companies for 2016-17 (the last year for which data was available) is analysed.

“It shows that there are 335 companies with profits of above Rs 500 crore, and they account for over 61% of the profits of this sample of over six lakh companies,” Mazumdar said.

“The figures show how concentrated corporate profits have become in the hands of a small number of companies. We would, of course, have to adjust for the fact that some of the companies with large profits are public sector firms — while taking into account that Indian business groups control multiple companies. The conclusion that a relatively small number of business groups or firms completely dominate the Indian private corporate sector would still be valid.”

Indeed, Mazumdar emphasises that even within this list of top 500 companies, the level of concentration might actually be higher than what is being indicated.

“That is because even within these 500, there would be more than one company belonging to the same group, controlled by the same business family.”

For example, Tata Motors, Tata Consultancy Services, Tata Steel, Tata Power, and the like are within the list of 500, but they are all part of the Tata group. Similarly, a number of companies are on the list that are owned by Reliance, both Anil Ambani’s Reliance group and Mukesh Ambani’s camp.

“Therefore, the concentration of profits amongst companies does not necessarily tell you what the level of concentration in India is, because we have the business group structure where one family can control several different companies across sectors,” he added.

Mazumdar also makes the point that post-liberalisation, while the share of private corporate profits has gone up in the total income generated within the Indian economy — from a range of about 5-6% at best in the early 1990s to around 18 to 20 per cent now — the distribution of these profits within the corporate sector has become more concentrated during the same time.

“While the private corporate sector has grown faster than the rest of the economy, thus increasing its share in total national income — again this means that now a very small number of families or companies are occupying a much more dominant position within the economy.”

Moreover, within the increased incomes generated within the corporate sector, the share that goes towards profits (and to other recipients of surplus incomes, like those who receive rent, etc.) has shot up disproportionately as compared to the share that goes to employees, over the past 25 years.

“Employees’ compensation would have accounted for something around 55% of the total income in the early 90s, today it is only about a third,” Mazumdar says.

“Rapid growth of the private corporate sector in the last two decades has been accompanied by a drastic redistribution of the income generated within it in favour of surplus incomes (mainly profits) — the wage share has declined drastically.”

Clearly, the invisible hand of the “free market” has not been able to sustain competition — at least not “free and fair competition”.

After all, how else would we have global monopolies like Google, Facebook, Alibaba and Amazon — given that there are millions of companies worldwide in the tech sector?

Also Watch: Inequality Gets a Hold of the World Through Globalization

And, what about the steady elimination of the public sector companies from the top 10, as noted earlier? One of the reasons for this is the relentless drive by Indian rulers to limit and even destroy the public sector, allowing the big industrialist a bigger slice of the cake. Opening up the market, deregulating nearly all sectors, privatisation of PSUs and framing policies designed specifically to favour and push private enterprises and sucking out their cash reserves are aimed at long-term destruction of PSUs, especially under the Narendra Modi government.

But finally, whatever factors one may attribute the corporate inequality to, the fact remains that inequality is a basic feature of capitalism — one that thrives through promoting the false narrative of ‘free’ and ‘fair’ competition under the ‘free market’. There is no free competition. Instead, it is just ‘winners take all’

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.