Neville Maxwell (1926-2019): My Academic Advisor at Queen Elizabeth House, Oxford

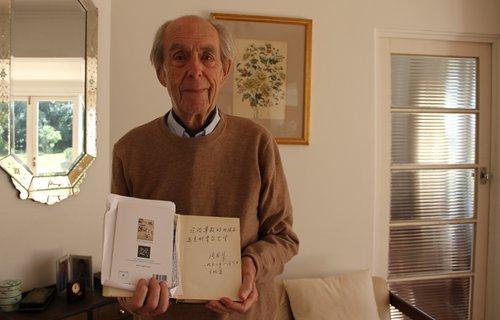

Neville Maxwell with his book India's China War. Image Courtesy: Global Times

Neville Maxwell, author of the well-researched and widely read book, India’s China War, 1970, died in September 2019 in Bowral, NSW, Australia. He had an academically fulfilling career and enjoyed a happy home life. In 1971, his controversial book played a key role in bringing about a historic meeting between US President Richard Nixon and China’s Chairman Mao.

I had the pleasure of meeting Maxwell in October 1983, when I went to Queen Elizabeth House (QEH), Oxford, on a visiting fellowship. Maxwell was my academic advisor. He was running a training and orientation programme for visiting journalists, civil servants and scholars. I was part of a group of five civil servants, and one scholar from India, who went to QEH for an academic year to study, travel and train under the Colombo Plan.

Soon after arrival in Oxford, we were asked to meet Maxwell, our academic advisor. As an academically inclined bureaucrat and director of the research and policy division of the Ministry of Home Affairs in New Delhi, I was familiar with the name of Neville Maxwell, famous for his book, India’s Border Dispute with China.

I had earlier read the Intelligence Chief BN Mullik’s book, Chinese Betrayal, 1974. Mullik was both ‘disciple and Guru’ of Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru and influenced him on key policy issues including on China. I knew of Maxwell’s important book but had only read parts of it at that time. The meeting between President Nixon and Chairman Mao, mentioned above, was crucially facilitated by Henry Kissinger, National Security Advisor to the US President.

Our meeting with Maxwell was hilarious. Brief introductions were followed by him asking us if we were comfortable and if there was anything he could do for us. One of our brash colleagues picked up courage and asked him if he could arrange a cup of tea for us every morning. Neville, who knew his India, laughed and said that if he meant ‘chhota hazri’, a colonial style bed tea, then such tea was available only in India. He advised the questioner to buy a kettle and tea bags to make tea for himself in his abode. This was a stirring start to our UK visit.

Maxwell also enquired if any of us had writing intentions. I said ‘yes’ but the others remained silent. As we came out, I was reviled by my friends for my ‘academic intentions’ which had embarrassed them; they were on a ‘paid holiday’ and intended to travel a lot. No writing for them!

So, while my colleagues planned to travel in Europe, I decided to sit down and discuss my writing plan with Neville. He appreciated my idea of writing a paper on the increasing violence against the Scheduled Castes in India and examining its policy implications. The subject was familiar to me from my Home Ministry days.

I spent a lot of time researching and writing my paper on ‘Violence against the Scheduled Castes in India: Overview, Problems and Prospects’. The paper was ready in a few months and circulated widely in the University. Neville liked it and suggested that I give a seminar on the subject at QEH. He chaired the discussions. My travelling colleagues were not present.

Interestingly, after my return to India in July 1984, I got a call from Nirmal Mukarji, Cabinet Secretary, who said he had received and read a copy of my paper. He had liked it. He invited me to a cup of tea. I enjoyed a private meeting with India’s top bureaucrat!

Neville, as my academic advisor, was always helpful and kind. Although a famous author himself, he was keen to learn from me. I told him that I had read only parts of his book, which was based on painstaking research.

A few months later, my family joined me at Oxford. Neville invited us home. We were delighted to meet his wife, Evelyn, and the boys.

Neville’s book on India’s border dispute with China was not well received in India. The author was perceived as anti-Indian since he had rejected India’s charge of ‘unprovoked aggression’ by China on the border issue. . I may briefly refer here to another book by Neville which he sent me later: China’s Borders: Settlements and Conflicts: Selected Papers 2012. The book has several important essays, especially one on ‘How to Settle the Sino-Indian Boundary Dispute 2012 (pp. 171-183).’ This essay rejects the perception that Neville Maxwell had an anti-Indian mindset.

In fact, Neville shows here that he was not all anti-Indian but was keen to help India and China in finding a peaceful solution to the border dispute between them. In this essay, he makes several constructive proposals on the border issue, which deserves careful attention by Indian and Chinese experts and policy makers.

He draws attention to the USSR/Russian/Chinese experience in border settlement and suggests that India could emulate the example of Gorbachev’s famous Vladivostok speech in 1986, which led to a border settlement between the two countries.

The author’s narration here is useful and instructive. The Russian experience was followed by three Central Asian successor states which also negotiated boundary settlements with Beijing. In this context, Neville appreciates the 1993 treaty signed by India and China on maintaining ‘peace and tranquility along the line of actual control in the India-China border areas which awaited follow-up actions. His essay in this volume is a republication of his article in World Affairs, July-September 2000.

Neville Maxwell's Introduction in this volume (pp.129-143) to the Henderson Brooks-Bhagat’s (HBB) Operations Review on the 1962 border war, is of immense value in understanding the Indian Army’s debacle. The report analyses the cause and course of the war; it then examines the schism within the Army’s officer corps.

Since 1950, the top of the Indian Army had split into two groups: i) a professional and apolitical group and ii) a nationalist group led by General BM Kaul. The Army chief Thapar was aligned to the latter. Army Headquarter was divided; the old guard evicted rivals and superiors. Army divisions fed into political divisions between those friendly to China and those who were not.

BN Mullik, Intelligence chief close to the Prime Minister, pursued a forward policy against China in the disputed areas. India held they were Indian areas. The Army high command, aware of its weaknesses, did not approve of the forward policy. Mullik’s forward policy led in October 1959 to a clash with the Chinese at Kongka Pass. The Army protest led Nehru to entrust the forward policy to the Army, side-lining Mullik, and rejected forward policy.

Kaul’s dominance in the Army HQ in 1961 meant intensification of the forward policy by Mullik who held with ‘unwavering consistency’ that the Chinese military, though strong, would not fight back. The falling out between India and China would have been to the liking of the US. Neville notes that the IB chief Mullik was in close contact with the CIA station chief in New Delhi Harry Rossitsky.

Briefly, HB/B concluded that political interference in promotions and appointments coupled with field level incompetence had led to the Indian Army debacle in 1962. They further note that BN Mullik, former Director of the Indian Intelligence Bureau (IB), was of the firm view that the Chinese “would not react to India’s new border posts and they were not likely to use force against any of our posts even if they were in a position to do so.” (emphasis in HB/B).

This opinion contradicted the conclusion of the Army intelligence 12 months earlier that the Chinese would resist by force any attempt to take back territory held by them. This was a conflict between the Army and the IB, which was a serious matter affecting the border operations.

The report added that appointments in General Staff and mistakes and lapses at HQ were more serious than errors in the field. The panicky, fumbling and contradictory orders by the Corps commander at Tezpur, had led to the debacle. The report added that two Generals of the Indian Army and a Brigadier were culpable. Neville concludes that the planners and architects were the Prime Minister, the Intelligence chief and a General.

Since the HB/B report was not a public document, no action was called for from the government. AG Noorani, an eminent legal authority, writing in The Hindu on July 2, 2002, rejected contrary arguments and demanded the official release of the HB/B report in the public interest, as promised in Parliament by the then Prime Minister of India, Jawaharlal Nehru.

In conclusion, it must be noted that Neville Maxwell was far from being disinterested in helping India and China to settle their differences over the disputed frontier. He was not militaristic. Despite his dissent with India, he was keen to find a peaceful solution to the dispute and came up with concrete recommendations in his article in World Affairs, July-September 2000.

Neville Maxwell continued to take keen interest in the developments in India-China relations during the Narendra Modi/Xi Jinping period. He continued to take note of significant positive features till his last breath.

KS Subramanian is a scholar and former member of the Indian Police Service. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.