Each Indian State Will Need Unique Lockdown Exit Plan

Image Courtesy: Indian Express

India has been under lockdown since 25 March to prevent the spread of the Novel Coronavirus, which causes the Covid-19 disease. By 29 April, more than 31,000 Indians were reportedly affected by the pandemic and this number is growing. The pandemic has also claimed over 1,154 lives. Fortunately, India’s death toll is lower than in many other countries, including the United States, Italy, United Kingdom, and Spain, who have paid the most humongous price in terms of loss of life during this pandemic.

In India, the nationwide lockdown is being credited with helping combat the outbreak even with limited resources. According to an estimate by the empowered group headed by NITI Aayog member VK Paul, India would have reached 1,00,000 Covid-19 cases by now if the country had not been locked down.

Yet at the same time, locking down with less than a day’s notice has hurt the Indian economy badly. Anxiety levels are mounting among employees; formal workers are expecting pay cuts as well as delays in appraisals whereas informal workers fear loss of jobs. For all these reasons, common Indians are expecting an exit from this locked-down state.

On 16 April, WHO Director-General TA Ghebreyesus warned at the mission briefing on Covid-19 that we may risk a resurgence which might be worse than the present situation, if countries remove social and economic restrictions too quickly.

Hence we need to review of situation across Indian states and plan accordingly for reopening the economy. No doubt India’s economy is on a knife’s edge and there is a need to strike a balance between saving lives and livelihoods. At the national level, the rate at which Covid-19 cases are doubling has slowed down, to 10.2 days from 4 days before the lockdown.

The growth curve is now comparatively flatter and the growth rate has currently declined to 16% from 20% prior to the lockdown, though the number of new cases is still growing, albeit at a steady rate.

The testing rate in India is still very low compared with other countries. By 25 April, India had conducted 5.8 lakh tests to detect Covid-19; or 420 tests per million population. And we do not know for sure whether the spread of Covid-19 infections and the fatality rate are really low in India or if the true number of cases is being masked by inadequate testing. If it turns out to be the latter, then India is seeing only the tip of the iceberg at the current rates of diagnosis and fatality.

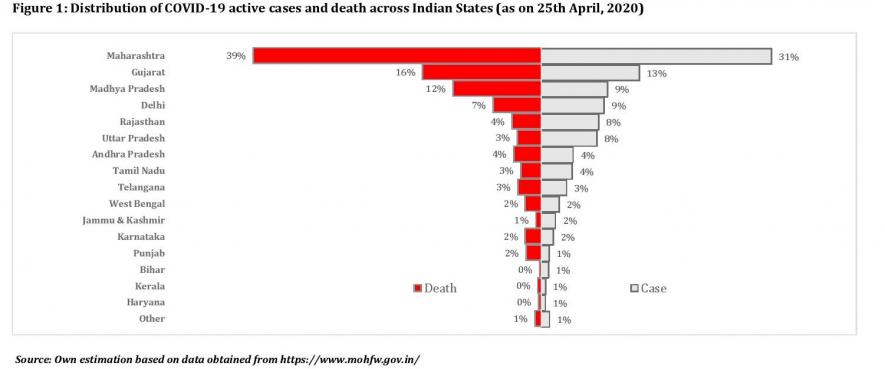

Moreover, the Covid-19 situation differs widely at the state level. Among the states, Maharashtra, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Delhi and Rajasthan have paid the heaviest toll for the Covid-19 outbreak. These five states account for 70% of Covid-19 cases and 78% of the associated loss of lives.

In the beginning of the lockdown—on 25 March—Kerala had 105 active Covid-19 cases. This increased marginally to 115 cases on 25 April, or a month later. Kerala’s share in the total active Covid-19 cases in the country has actually gone down significantly, from 19% to 1% over the lockdown period.

Quite alarmingly, in Maharashtra, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Delhi and Rajasthan, the reverse trend has been visible: in these states and regions, the number of active Covid-19 cases have increased by 50, 72, 128, 71 and 47 times respectively during the month-long lockdown.

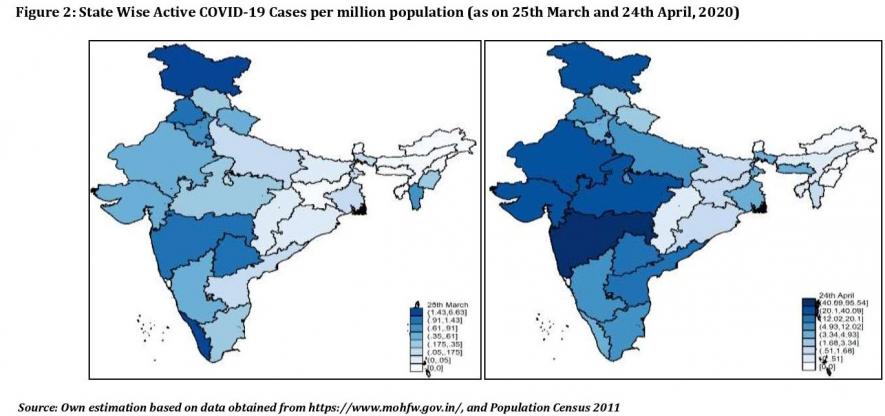

Figure 2 shows the relative position of all Indian states in terms of active Covid-19 cases on 25 March when the lockdown began and on 25 April, one month into the lockdown. From this it is clear that even after one month of lockdown, Maharashtra (with 51 active cases per million population) remains the epicentre of the outbreak in India. The spread of the virus is also high in states neighbouring Maharashtra.

Active Covid-19 cases per million state population in Maharashtra, Gujarat, Madhya Pradesh, Delhi and Rajasthan has increased from 1.1, 0.6, 0.2, 1.4 and 0.5 to 50.5, 40.1, 21.3, 95.4 and 25.9, respectively during the first one month of the lockdown.

Eastern states remained relatively less affected by the pandemic. But West Bengal (with 5 active cases per million population) is gradually emerging as a new epicentre of the region. The share of West Bengal in India’s total active Covid-19 cases increased from 1.4% to 2.4% during the lockdown period.

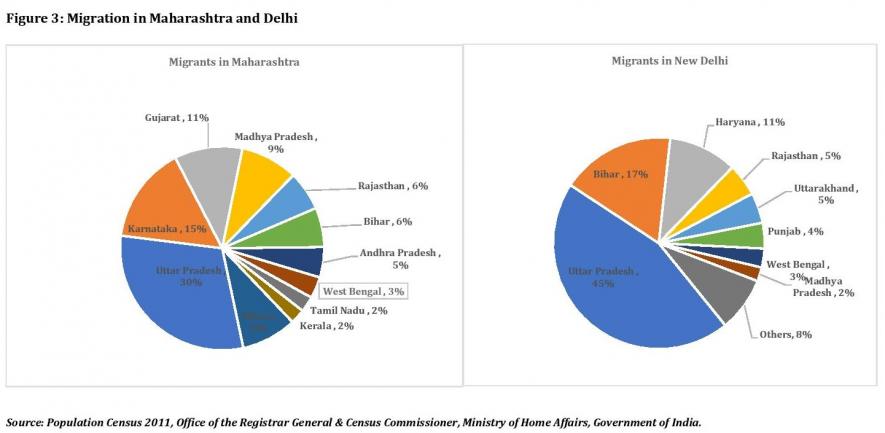

Maharashtra and Delhi, which are among the five most-affected provinces in India, attract a large number of migrants from neighbouring states as well as from the backward states such as Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. According to the latest (2011) Census, Maharashtra and Delhi attract 17% and 12% of the total interstate migrants in India. Of the total migrants living in Maharashtra, 30% are from Uttar Pradesh and and 6% from Bihar. Similarly, 45% and 17% of total migrants residing in Delhi are from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar respectively. An immediate withdrawal of the national lockdown may radiate Covid-19 infection towards Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and other states through reverse migration from existing epicentres in India.

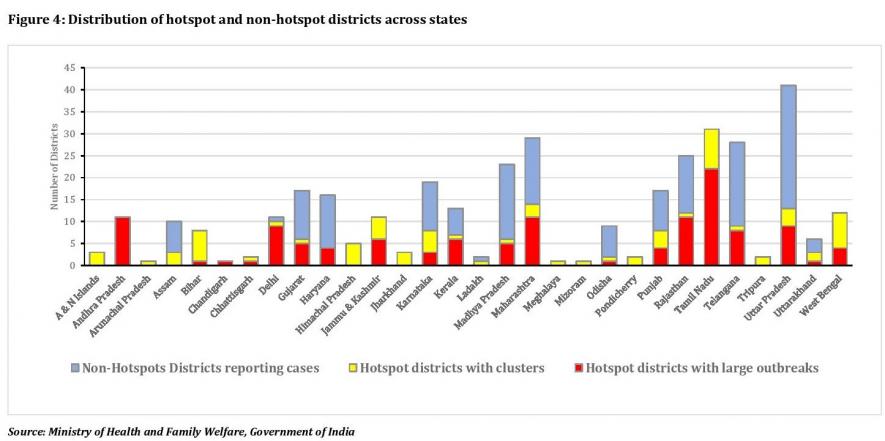

As evident from Figure 4, the lockdown helped contain the spread of the virus to certain districts within states. After the lockdown is lifted, the virus can make a resurgence in two ways when people start travelling for the jobs, school, colleges, and the market opens. First, some estimates show that 1 in 4 coronavirus carriers do not show any symptoms and that there is significant transmission by these ‘asymptomatic’ people.

People who are not aware that they are sick can being a new wave of virus transmission when they come in contact with, say, older and more vulnerable members of the population. Second, even if international travel is banned, cross-country travel involving two or more states would spread the virus to remote corners of the country where people have not yet been exposed to the infection.

Many European countries are preparing to reopen their economies, though in multiple phases and at different paces. Governments are providing masks to citizens upon relaxing their lockdowns so that people maintain social distancing and stick to the suggested hygiene practices. At the same time, gatherings of more than a few people are still being restricted in almost all countries.

In the absence of a robust health system for the whole country and sufficient resources to ensure safety to every worker, one option before India is to choose another short span of lockdown along with frenetic and intensive testing for Covid-19. But in that case, the states should ensure the distribution of essential commodities to the poor and vulnerable sections of the population.

Another option is for the government to initiate a phase-wise withdrawal of the lockdown without reopening state and national borders immediately. For example, some relaxations could be provided to farmers. The procurement of their produce should be ensured since agriculture provides livelihood to a majority of the population in India.

Districts which has reported a low number of cases can be reopened. More precautionary measures are needed for urban areas, particularly large cities, which were exposed to the virus more and where the disease is more prevalent as a result.

In short, while easing restrictions regional disparities in the scale of infection should be considered vis-a-vis the capacity of the health system. The government needs to come up with a detailed phase-wise plan for different states and regions; and for the various economic sectors, associated offices, shops and public institutions, which can then be reopened successively.

The government should also ensure safety of employees through sanitisation of workplaces and provision of masks. Since health is a state subject, central and state government should work hand-in-hand to strengthen the public health system. In the meantime, state governments also need to step in and take care of vulnerable sections of the population along with the migrants living in their territories.

Pritam Datta is a fellow at the National Institute of Public Finance and Policy (NIPFP), New Delhi, and Chetana Chaudhuri is senior research associate at the Public Health Foundation of India (PHFI), Gurgaon. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.