Why Smart Cities Are No Answer to Covid-19

Representational image. | Image Courtesy: Financial Express

It has been five years since India’s ambitious Smart Cities Mission (SCM) was announced. It is fair to say that not much progress has been made. Currently, less than half the cities have even been started and in a third of chosen cities not a single project has been completed. But, interestingly, Covid-19 and the subsequent problematisation of Indian urbanism has given them renewed impetus, support and justification.

The idea that smart cities could combat Covid seems to have taken hold among supporters of the Mission. In June, #CitiesFightCorona and #transformingIndia were being pushed on Twitter by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs, the SCM and several municipal authorities. There have also been countless articles arguing that India’s road out of this crisis runs through the smart city. So, before we explore how this crisis might actually revitalise the SCM, its important to think about how we got here.

Launched by Modi in 2015, the SCM is a nationwide city building and upgrading programme. It seeks to establish 100 smart cities through upgrading, retrofitting or building them from scratch. If implemented in existing cities, it either takes an area-based development (ABD) approach or a pan-city one. ABD commands about 80% of the funding and focuses on districts or communities within cities. It has been criticised for targeting already affluent areas and populations—some estimates of ABD projects suggest they benefit only 4% of the urban population and cover merely 3% of city areas.

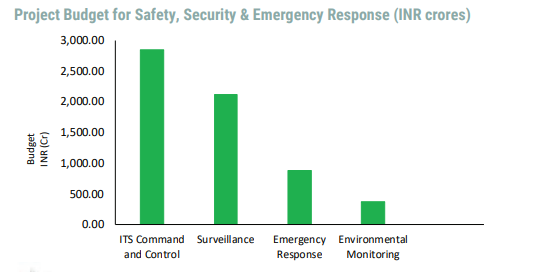

Pan city, on the other hand, are city wide projects. However, most initiatives are more about surveillance and control (CCTV, facial recognition, security systems, etc), rather than sanitation, infrastructure or environmental protection. For example, a 2019 Smart Cities India report on Safety, Environment and Emergency Response in the SCM showed that surveillance had a project budget of Rs. 2,000 crore, while environmental monitoring had less than Rs. 500 crore (see graph).

Source: https://www.smartcitiesindia.com

What’s more, in order to gain “smart city status”, you have to compete for it. In a clear sign of the lack of a coordinated national urban policy from the centre, cities have to compete with one another for investment and support. The 100 winning cities, home to an estimated 100 million people, are ranked, graded and presented in table form from best to worst. The total funding for projects in the SCM is around $30bn and the Centre has promised roughly Rs. 100 crore per city per year, although many observers say this figure is far too low to implement the changes suggested.

Public-private partnerships are therefore a key means of financing such projects and municipalities are having to court private investment with profitable opportunities.

The SCM and Covid-19:

How then has Covid-19 breathed new life into the SCM after five years of missed targets, widespread criticism and faltering business interest? Tellingly, Kunal Kumar, SCM Mission Director, in a piece co-authored with Jaideep Gupte, a research fellow at the Institute for Development Studies, said “India’s response to Covid-19 now depends on the successful use of its smart cities investment.”

For Kumar, “slowing down the spread of Covid-19 is going to require, among other things, a heavy reliance on India’s data infrastructures—providing real-time data readings for critical decision making—and its Smart Cities Mission.” That was back in April and, to their credit, many city authorities in India have been deploying innovative technological responses to the pandemic, furthering the idea that technology holds the key to what has predominantly been an urban crisis in India.

Agra is often the held up as an example. The city administration has been teaming up with tech companies which have provided valuable services that can track Covid-19 cases and have developed apps to identify contacts, hotspots and localised trends. Amrita Chowdhury, director of Gaia, a Mumbai-based tech company that works on smart city services and has been helping authorities in Agra, explained that “citizens using the platform can self-assess and this information is then passed on to city authorities. Thereafter, a pincode-wise mapping is done where medium and high-risk people are identified.”

However, while such applications may have helped track the spread of Covid-19 in cities like Agra, they have done little to address the underlying problem of inadequate health infrastructure in India. An analysis by the Indian Express noted that only 69 of 5,861 of projects in the SCM were focused on health infrastructure and capacity building. And, of the more than Rs. 2,00,000 crore in smart city funding, only 1% went towards health care. Considering Delhi is transforming 25 luxury hotels into hospitals because of a lack of capacity, the logic of the smart city that privileges technology infrastructure over health or sanitation infrastructure appears increasingly flawed.

It seems as if the SCM approach contains a blind faith in the ability of technology no matter what. It is all very well that “45 cities have operational Integrated Command and Control Centres (ICCCs) set up under the smart cities mission,” as Kumar reminded us, but how many hospital beds and ventilators are in those cities?—a recent investigation by CDDEP found that India has roughly 1.9 million hospital beds, 95,000 ICU beds and 48,000 ventilators, unevenly distributed, across India’s 1.3 billion population.

Prior to Covid-19 the SCM was about creating economically attractive, high-tech business cities that transcended some of the major infrastructural issues with existing Indian cities, yet did not care too much about health infrastructure. Contrary to the views of some, Covid-19 should be used to highlight inadequate healthcare infrastructure and not further the primacy of technology in addressing urban issues.

There are signs that some changes are occurring but, with the economic logic embedded in the smart city mission unable to accommodate wide-scale transformations in healthcare provision, there is little hope it will result in greater access and quality of care for the majority. “Cities define what smartness they want,” said Hitesh Vaidya, director of the National Institute of Urban Affairs, “and health did not figure as prominently. The major focus was to make a city economically vibrant, but now with Covid-19, we will realise that you can only be an economic engine if your people are healthy.”

The author is a freelance journalist with an interest in how geography, housing and architecture reflect and reform social relations in the city. He has written on slums, smart cities and traditional design in the Indian context.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.