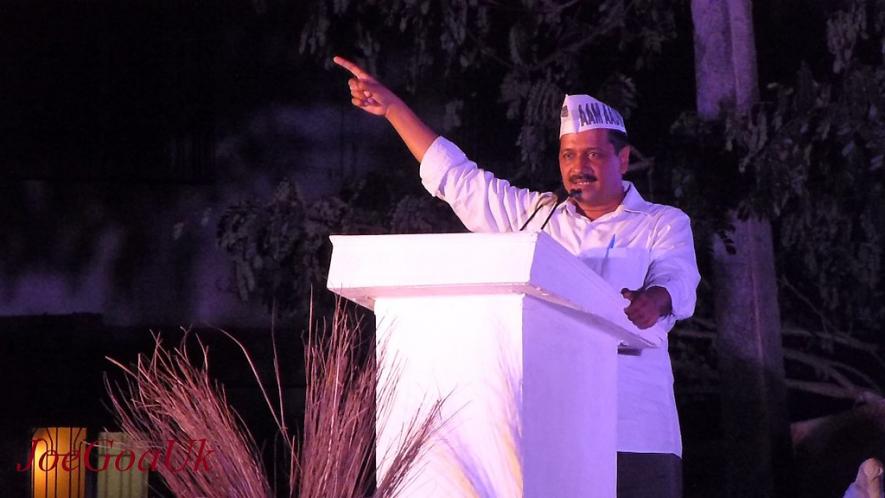

Can Kejriwal Emulate Hanuman, Build a Bridge Between Hindus and Muslims?

The Aam Aadmi Party’s model of governance became the bulwark against the attempts of the Bharatiya Janata Party to communalise the Delhi Assembly elections and turn it into a Hindu-Muslim battle. The benefits accruing from Delhi Chief Minister Arvind Kejriwal’s emphasis on social welfare measures were just too many for Delhiites to have them succumb to the BJP’s tactics of scaring the Hindus into ditching the AAP.

Delhi’s significance in India’s electoral politics is limited, sending as it does just seven MPs to the Lok Sabha. Yet the city’s salience grew manifold in the backdrop of the Modi government enacting the Citizenship Amendment Act, which was projected as a measure to provide relief to the Hindus who had fled religious persecution from the Islamic countries of Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan.

Thus was created the Hindu-Muslim binary barely two months before the Delhi Assembly elections.

The BJP sought to exploit this binary as protests against the CAA and the interlinked processes of preparing the National Population Register and then the National Register of Indian Citizens broke out countrywide. The BJP chose to portray the round-the-clock sit-in at Delhi’s Shaheen Bagh as an example of Muslim intransigence, which the Hindus must oppose for their own safety by voting out the AAP from power.

The Assembly election results are a telling testimony to the BJP’s failure to scare the Delhiites. The AAP won 62 seats, dropping just five seats, and facing an erosion of less than 1% in its vote-share of 54.3% that it had bagged in 2015. The BJP’s politics of communal polarisation fetched it five more seats, up from three, and augmented by 6% its kitty of a 32.2% vote-share.

These statistics will have pundits assert that good governance and providing tangible benefits to people across the class divide is the only effective counter to the BJP’s Hindutva, which fans hatred between Hindus and Muslims for driving a wedge between them.

This was evident in Kejriwal’s electoral strategy—he insisted on projecting the elections as a referendum on his five years of governance, largely resisting the temptation to enter into an acrimonious debate with the BJP over Shaheen Bagh, although his party had voted against the CAA, in contrast to supporting the reading down of Art 370. Kejriwal did periodically speak against the CAA-NPR-NRIC triad during the election campaign, arguing that the citizenship issue would not enable the country to develop or create jobs.

At times, though, the AAP slipped in maintaining a carefully-cultivated distance from Shaheen Bagh. For instance, AAP leader Manish Sisodia said he stood with the protestors of Shaheen Bagh. The BJP projected Sisodia’s remark as proof of his pro-Muslim sentiments.

To counter the BJP’s strategy of inspiring the Hindus to vote on the issue of identity, Kejriwal projected his Hinduness by reciting the Hanuman Chalisa and harped on being a bhakt of Lord Hanuman, who is popularly represented as the deity of plebeians. It is they who have tremendously benefited from the AAP government and constitute Kejriwal’s nucleus of supporters. Kejriwal was dissuading them from believing the BJP’s propaganda that AAP leaders are pro-Muslim, or against the interests of Hindus, and deserting him.

Kejriwal’s strategy testifies to the right-wing shift of Indian politics. This in itself is not novel—Congress leader Rahul Gandhi, for instance, went on a temple spree to emphasise his Hindu identity. The Congress’ manifestos for Rajasthan and Madhya Pradesh, released before their Assembly elections in 2018, promised several palliative measures relating to the cow. The Congress won narrowly in both States and formed governments there, but received a drubbing in the 2019 Lok Sabha elections five months later.

Likewise, the AAP has overcome its comprehensive defeat in the Lok Sabha to win the Delhi Assembly; its scale of victory enormous in comparison to that of the Congress in Madhya Pradesh and Rajasthan. This comparison raises several questions: How do Opposition parties wrest states from the BJP where, unlike the AAP in Delhi, they are not in power and do not have a model of governance to showcase? Do they need to wait for anti-incumbency to emerge before hoping to sweep into power?

More significantly, in the absence of strong sentiments against BJP governments, will their attempts to play on a softer, benign, inclusive version of the Hindu identity enable them to grab power? It would have been impossible for AAP to return to power without good governance. The party’s projection of its Hinduness was merely designed to neutralise the pull of Hindutva.

Yet, it is debatable whether the Opposition parties can aggregate good governance in a chain of states to dislodge the BJP from the Centre. It should be palpable from the electoral trends of the last six years that people vote differently in state and national elections. Parties in power do enjoy an inherent advantage in setting an agenda for an election. This advantage in the next national election lies with the BJP, even though its record on this score, as of now, is dismal, evident from the slowing economy and the social unrest countrywide.

Opposition parties will find it hard to convince the people that they can govern better than the BJP at the Centre. They are neither united nor have a personality whom they can project as an alternative to Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

An alternative to Modi would ordinarily come from the Congress party, which still has a national footprint. The brand of Rahul Gandhi, however, seems to have been irreversibly devalued. It is unlikely that voters will credit the performance of Congress governments in, say, Rajasthan or Chhattisgarh to Gandhi.

Governance, therefore, does not seem an adequate weapon to fell the BJP or Modi. It has to be supplemented by articulating and deepening the idea of belonging to India.

Indeed, the Delhi Assembly elections brought into conflict two ideas of citizenship. The BJP represents citizenship based on descent, privileging the Hindus over all other religious groups. The CAA is one big leap towards turning India into a homeland of Hindus.

AAP, on the other hand, represents what political scientists call the “service-delivery citizenship”, where the state offers civic amenities and delivers public goods—electricity, power, education and healthcare—to all citizens regardless of their religion, caste, class and language.

There is a certain universalism to the AAP’s conception of citizenship. This is evident from its manifesto, which has as its opening line: “Aam Aadmi Party makes a commitment to the people of Delhi to serve and uphold, justice, liberty, equality, fraternity enshrined in the preamble to the Constitution of India as fundamental to our governance model.”

The manifesto also reflects the civic idea of citizenship—for instance, it provides a greater participatory role to Delhiites in governance, reminding them that it had approved the formation of 2,972 mohalla sabhas in the city for devolving power to the grass-roots. This could not be implemented because the central government sat on the Delhi Nagar Swaraj Bill, through which mohalla sabhas were to be empowered. The manifesto promises to pressure the Centre to clear this bill.

Delhiites seem to consign the two ideas of citizenship to two separate realms, as I and other journalists found in our conversations with them. They think it is the responsibility of the State or Union Territory governments to execute the idea of service-delivery citizenship. For them, the state is the site where the public goods are to be delivered.

By contrast, the central government’s duty is to weld together a larger national community through symbols such as the national flag, the armed forces and projection of India’s power globally. They did think, rather worryingly, that the nation and the Hindu are, to a large extent, synonymous.

The inclination of Delhiites to simultaneously live with the two ideas of citizenship underscores the possible limits of using development for challenging the BJP at the national level. This limit can only be breached through an ideological battle against the BJP, which certainly also involves denying the party sole monopoly over the religious and cultural realms.

There is a crying need to explain to the Hindus why Hindutva is destructive of the national interest, or why the BJP’s ideological obsession and its propensity to spark social conflict distracts from and undermines governance. More pertinently, they have to be explained why the CAA-NPR-NRIC adversely affects their interests, not just of the Muslims.

After his party’s stupendous victory, Kejriwal paid obeisance to Lord Hanuman, who in the epic Ramayana built the bridge to Lanka for enabling Lord Ram to wage war against Ravana. To take on the BJP, Kejriwal needs to emulate Lord Hanuman and build bridges between India’s social groups, of whom the Muslims particularly were brutalised by the state in his own city. This is the surest route for Kejriwal and AAP to revive their national ambitions, at which they have got their third shot.

The author is a freelance journalist. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.