How Economic Survey Masks Real Number of People Excluded from Food Security

The government’s Economic Survey 2020-21 has made a number of observations regarding the country’s efforts toward enabling substantive food security. Highlighting the government’s attempts in this direction, the Survey goes on to state that “against all adversities due to COVID-19, continuous supply of agriculture commodities, especially staples like rice, wheat, pulses and vegetables, has been maintained, thereby enabling food security.” The Survey notes, in particular, the role played by the Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Anna Yojana (PMGKAY) in light of the pandemic, stating it to be in pursuance of its “pro-poor” pandemic relief package.

Announced as a part of the Rs 1.70 lakh crore Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan relief package on March 26, 2020 by the Union Minister for Finance & Corporate Affairs, the PMGKAY had the stated objective of providing 80 crore individuals (i.e. all beneficiaries under the National Food Security Act) with double their current foodgrain entitlements over the next three months, free of cost.

Purportedly to protect India’s poor from suffering “on account of non-availability of foodgrains,” the announcement achieves salience when one notes the extent of the economic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic. Data compiled from news portals indicates that of the 884 “non-virus” reported deaths in India due to the lockdown as of July 2, 2020, at least 167 were directly caused by starvation and financial distress.

Furthermore, surveys by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) indicate that the unemployment rate in India reached 23.5% in April and May 2020, testifying to an undeniable increase in concomitant food insecurity. Analysis of survey data collected as a part of CMIE’s Consumer Pyramids Household Survey reveals that over 80% of the surveyed households reported a decline in income owing to the national lockdown that was ordered from March 24, 2020.

Although the Survey states that nearly 121 lakh tonnes of foodgrain was allocated to approximately 80.96 crore beneficiaries under the PMGKAY, data made public by the Department of Food and Public Distribution evidences this as a misrepresentation of the number of people who have fallen through the cracks in India’s food security policy.

Table 1: Comparative distribution of foodgrain through NFSA and PMGKAY, April-June 2020

Source: Department of Food and Public Distribution

The total amount of foodgrain that has been distributed under NFSA for April, May and June 2020, i.e., for the three months that were initially covered under PMGKAY, was 124.35 lakh tonnes. In comparison, the cumulative distribution (as opposed to the mere allocation that the Survey lays emphasis on) under the PMGKAY over the same period was 100.68 lakh tonnes, indicating a shortfall in distribution of foodgrain of nearly 24 lakh tonnes.

Simply comparing foodgrain distribution under PMGKAY with distribution under NFSA, however, is a further underestimation of the overall shortfall. The government’s statutory obligations under NFSA to all entitled stakeholders implies that there ought to be a monthly foodgrain allocation of 43 lakh tonnes. Taking this figure into consideration, the cumulative shortfall in distribution of foodgrain under both NFSA and PMGKAY over the three months reaches nearly 33 lakh tonnes. The total stock, however, including unmilled paddy held by Food Corporation of India (FCI) over the same period notably registered an increase of nearly 220 lakh tonnes.

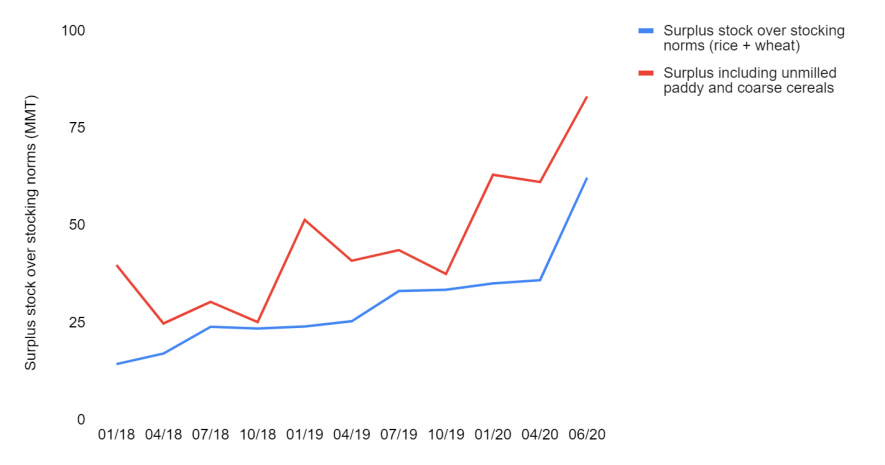

It is in this context that the government has faced criticism from multiple quarters for not having universalised the public distribution system or PDS despite FCI holding record-high stocks. As of June 2020, FCI held combined rice and wheat stocks of 832.7 lakh tonnes, significantly higher than the 210.4 lakh tonnes and 411.2 lakh tonnes that is required to be held as per buffer stock norms (for 01.04.2020 and 01.07.2020, respectively).

This situation has mainly resulted owing to the government’s reluctance to offtake grain from FCI to keep its fiscal deficit low; the costs are thus passed on to the books of FCI, which is increasingly forced to rely on borrowings to cover its losses. It is thus that the Economic Survey’s assertion of “a need to consider the revision of CIP (central issue prices) to reduce the bulging food subsidy bill,” needs to be questioned.

Figure 1: Foodgrain held by FCI in surplus of stocking norms, January 2018 to June 2020

It is to be noted, however, that even the above necessarily underestimates the number of people in India who are excluded from any measure of food security. In an article, Meghana Mungikar, Jean Drèze and Reetika Khera recently estimated that owing to exclusion errors stemming from the purposive use by the government of outdated population estimates, over 108 million people in India have been left out of PDS coverage. They note that while 922 million people should be eligible for foodgrain transfers under PDS based on population projections in 2020, transfers continue to remain restricted to only around 814 million people.

As a result, ration card applications of millions of low-income families do not get processed by state governments whose quotas have now expired. In Jharkhand, applications of over eight lakh families are said to be pending. This does not include all those who are also excluded due to other reasons, including the lack of documentation, such as Aadhar, as is to be expected from any identification exercise. Dreze, in this regard, estimates that NFSA’s actual coverage is only 60% of the population, as opposed to the 67% that it is said to cover.

However, food insecurity was an alarming problem in the country even before the effects of the pandemic took hold. Estimates based on the National Sample Survey Organisation’s (NSSO) 68th Round Consumption and Employment Surveys indicate that in 2011-12, the number of undernourished people in India stood at 472.2 million, which is nearly 40% of the Indian populace—ranging from 1.7 million in Himachal Pradesh to 73.9 million in Uttar Pradesh.

Estimates derived from the Food and Agriculture Organisation’s 2020 edition of ‘The State of Food Security and Nutrition in The World’ indicate that the number of people living in India with food insecurity increased by 62.1 million between 2014 and 2019, from 426.5 million to 488.6 million. The Economist Intelligence Unit’s 2019 Global Food Security Index places India at 72 among 113 countries. The Index’s Sufficiency of Supply indicator in this regard ranks India 16th among 23 Asia-Pacific countries, wherein India notches a composite score of 47.3 as opposed to the world average of 62.9.

India is also ranked 102nd among 117 countries on the 2019 Global Hunger Index, with a hunger-level categorised as serious. The above necessitates a more comprehensive public discourse on the policy responses to food insecurity, as opposed to the simplistic reductionism that the Economic Survey attempts to propagate.

The writer is a Research Associate at the Social and Political Research Foundation, New Delhi. The views expressed are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.