Why Kashmir Will Boomerang on India

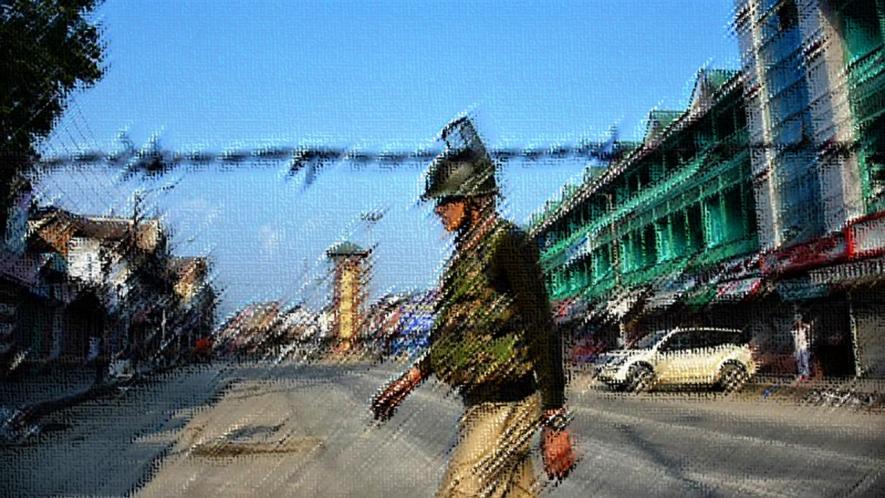

Representational image. | Image Courtesy: aljazeera

Much of the discussion, rightly so, since the abrogation of special status of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K) has been on its impact on Kashmiris. What also needs to be considered with equal intensity is its consequences on the rest of India. It is clear that Kashmir will do more of what they have been compelled to do for over five decades: resist and fight for dignity. But how will India negotiate the fallout of the dynamics unleashed by the stamping out of Article 370? India has now openly acknowledged and confessed an imperialistic expansionism that has popular consent. Yet, this expansionist tendency is by no means going to end with Kashmir.

Many other debates related to human rights in India will be dramatically impacted by the dominant narrative of expansionist cultural nationalism presently unleashed in Kashmir. When the chickens come home to roost, would Indians who are cheerleaders of the Centre’s moves in J&K have the will and the narrative to face it?

The argument being proffered in support of revoking the protection of Article 370 to Kashmir is that Indians would now get the right to buy land in the region. That they would be able to take up economic activities in J&K. This argument would come full circle in many ways. To begin with, it would get linked to the question of all other backward regions in India. Is it any longer justified for Bundelkhand, Vidharbha and other regions that are lagging behind from raising a demand for separate statehood?

Instead of offering protectionism and allocating additional funds in response to these region’s demands, would it not be the argument of the incumbent government to withhold funds and ask private players to take over these regions? The private players, in the name of development, can then undertake extractive activities in these regions as well.

It is instructive to observe that even before abrogating the special status for J&K, the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) under Prime Minister Narendra Modi has not granted special status to Bihar and Andhra Pradesh. Special status, presumably, is being denied because it would fly in the face of the BJP’s abstruse arguments in favour of “one nation, one market”. In other words, what removal of Article 370 protections has done is to bring into question the very legitimacy of any special provisions.

This could further extend to the tribal areas of Central India where, invoking the principle of Eminent Domain, the government can take over land and resources and deploy them to serve its own vision of ‘public’ or ‘national’ purpose. Such an eventuality would not be a surprise given the cunning ‘reason’ that the BJP and Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) combine have used so far. There is every possibility that this combine would hit back, arguing that if the special provisions made for Kashmir—which had a disputed territory status—could be abrogated in the “national interest” then there is no justification not to extract resources via large-scale mining in Central India either.

The parallel between “Kashmiri jihadis” and Maoists is readily available with the state in order to push this narrative even more violently. Given the slump in the economy, the state could become all the more desperate to hit the brakes on the downward spiral by expanding extractive activities. The result would be mass displacement of tribals, which could then be compared to the kind of rehabilitation of Kashmiri Pandits have got—in specialised zones, under state protection.

Uncanny parallels of this kind cannot be ruled out given the arguments that the RSS-BJP combine have been offering in the context of Kashmir. One of the arguments being bandied about relates to rehabilitating the Dalits of Jammu in the Valley. The other is that reservations for Scheduled Tribes and Scheduled Castes (SCs and Sts) in J&K would provide new opportunities to discriminated social groups.

Even as reservations are being invoked to justify the Centre’s moves on Article 370 and in its attempts to revoke the special provisions for minority institutions in India, the veracity of caste-based reservations is itself being questioned as a blot on the ‘unity’ of the Hindus. Moving from caste based reservations to reservations on the basis of economic criterion is already on the cards for the BJP. They are only awaiting the right opportunity to delegitimise caste as a ground on which reservations have been implemented so far.

The first salvo against caste-based reservations was fired when the roster system in public universities was openly tampered with. Next came the attempts to repeal the SC and ST (Prevention of Atrocities) Act in its just-concluded first term in power. It has remained a consistent strategy of the BJP to pitch Dalits and the Other Backward Classes against the Muslims. From tweaking history to the riots that took place in a Dalit colony of Trilok Puri in Delhi, to condemning the protests that followed the suicide of Hyderabad Central University scholar Rohith Vemula, by reading it through the lens of its support to Kashmiri separatists: After each of these incidents the BJP took a position consistent with its aim to stamp out the protests of oppressed social groups against their discrimination.

Along with the question of land and economic resources the developments in Kashmir have brought back gender and empowerment of women. The Modi government has made noises in favour of empowerment of Muslim women by revoking instant triple talaq and criminalising it. At the same time, the party’s elected and public representatives have inaugurated the fantasy of “marrying fair-skinned Kashmiri women”.

Colonising its land and women will reset the terms of the debate of the rights of women in India. It will push the debate back to a far more traditional imagination. Pracharaks of the RSS are known for issuing statements that glorify the [traditional] Indian family system. In their imagination the status of women is such that they should be confined at home and limited to the private sphere.

In a symbolic sense, the resistance in Kashmir had at a subterranean level already invoked the gender question. There was increasing participation of college-going women in street protests. Their participation was a kind of rebellion against the dominant narrative of Islamic conservatism on gender issues.

Finally, the developments in Kashmir are also important for the way in which the military and the forces were deployed against dissenting Kashmiris. In an unprecedented move, their telephonic, mobile and Internet connections were blocked. This move triggers a new imagination as to how dissent can be controlled, by completely stamping out all means of communication. It cannot be ruled out that in future protests in ‘mainland’ India could also be dealt with in a similar way, as these methods have got large scale consent.

Surveillance and the control over the media had gained credence through schemes such as Aadhaar and by repealing provisions of the Right to Information Act. It is only the next step to use similar methods whenever the next controversial decision is to be taken by the government. What can be cited is how effective such means have proved to be in Kashmir, where it was used in the “national interest”.

Justice has a delicate and complex template. It is firmly based on the idea of solidarity. In generating large-scale consent for exceptionalism, the current regime has silently managed to garner the tacit consent of the majority for methods that are bound to rebound on them. The problem with the experiential aspect of justice has always been, as the American critical theorist Nancy Fraser observes in elaborating on socialism, that it is “morally compelling but experientially distanced”. What kind of political narrative can alert the majority of Indians to the dangers lurking behind such expansionism should engage us collectively in the times to come.

Ajay Gudavarthy is associate professor, Centre for Political Studies, JNU. The views expressed are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.