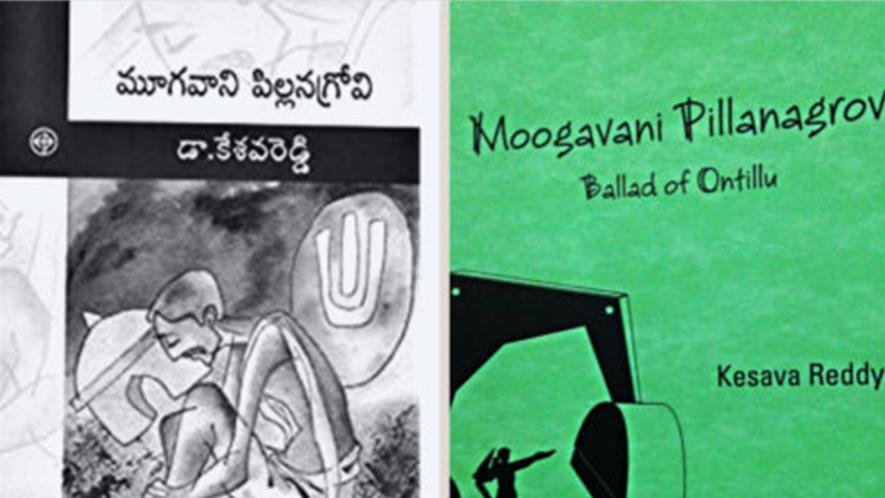

Moogavani Pillanagrovi: Ballad of Ontillu

Translation is not just about words, it is about carrying a culture, a history, a whole world into another language. Translations do not just bring languages closer to one another, they also introduce us to diverse modes of imagining and perceiving different cultures.

To mark the International Translation Day, celebrated on 30 September, the Indian Cultural Forum will be doing a series of posts to emphasise the power and importance of translations.

'Moogavani Pillanagrovi’ literally means ‘the mute boy’s flute’ and is the story of Bakkireddy the farmer, his loss of land and subsequent death. Written in Telugu by Kesava Reddy, fiction is interwoven with local myths and superstitions regarding land and forest in 'Moogavani Pillanagrovi: Ballad of Ontillu'. Although set in rural Andhra of the 1950s, the issue the book tries to address resonates with contemporary Indian society plagued by an agrarian crisis and consequent farmers’ suicides. Translated into English by Kesava Reddy himself, the original work was published in 1993, around the beginning of agricultural distress in Andhra Pradesh.

Below are excerpts from the chapter Condemned and the Epilogue of the book.

Bakkireddy lay back on his cot. The moaning and wailing in the courtyard had long since died down. His heart had stopped pounding against his chest and was beating normally. The sun had cooled considerably. The shadow cast by the cattleshed lengthened and stretched across the street. The crows that had been out foraging all day returned to the tamarind tree. Perched on its branches they were making a raucous din. Since midday he had confined himself to his cattleshed.

Where could he go, after all?

Why he could have gone to neighbour Narasimha Naidu, who lived on Temple Street.

He could sit with Narasimha under the hayrick behind his house and talk about the vagaries of the weather. ‘It has been sweltering for two days. Looks like we might see the first rains tomorrow or day after tomorrow. The clouds might descend over in the northeast corner. Then again they might come down in the southeast corner. How much rain would we get? May be so little that the plough shear would not cut more than four fingers deep. Or, may be so much that the river would flood and the tanks fill the sluices and spillways.’ Issues such as these he would talk over with his neighbours. ‘But I am no longer a farmer’, he thought, ‘I have lost my land. What would it matter to me if the tank was full or dry? For that matter, why should I care even if thorn trees grew in the tank?’

But where could he go, after all?

He could go to Gangireddy, who lived on Lower Street. He could sit with him on the pyol and talk about crops, ‘Which of the varieties of paddy suits this season? How high would such and such paddy grow? Which pest would give the paddy most trouble? How many months would it take for whatever paddy to grow through milk seed? And how many weeks would it take to harden and be ready for harvesting? And what would be the per acre yield?’ Matters such as these he could discuss with his friend. ‘But I am no longer a farmer myself’ he said to himself, ‘my land has been snatched from me, the way a chick was snatched from a mother’s hen by a hawk. As things now stand, I am not even worthy of sitting next to Gangireddy.’

Where could he go, after all?

Why, he could go to the carpenter who lived on Boulder Street. There was a shack behind the carpenter’s house, which was his workshop. There he was always seen, busy with saws, chisels, adzes, draw knives, and planes, all the usual tools of the trade. He could go to him and say, ‘Friend, I must have a new plough ready before the day is over. Look at the way the clouds are moving! The first rains are sure to begin in a day or two. The Brahmin consulted the almanac and pronounced as much. The minute the rain drops touch the ground, I must harness the plough and before the moisture is sucked up I must plough my field at least three times. Problems such as these he could share with the carpenter. But I am no longer a farmer,’ he reminded himself, ‘I sold my land in an auction like King Harischandra* sold his wife. What need do I have for a new plough? What would it matter to me, even if the old one was eaten by termites?’

Where would he go, after all?

Why, he could go to the blacksmith, who also lived in Boulder Street. His smithy was under a tamarind tree not far from his house. There he could always be seen banging away on his anvil working with his hammer and tongs on some piece of iron. Bakkireddy could say to him, ‘Friend, you must spare some time for me. For my bulls need your service urgently. Their hooves are worn away and blood is dripping from them. They need to be new shod at once. Can you come to my house with your implements or do you want me to bring the bulls here?’ Favours such as these he could seek for him. ‘But I am not a farmer any longer’ he mused, ‘I’ve lost my land the way a mother loses her child in an abortion. It could make no difference whether the bulls are in the cattleshed or killed and devoured by leopards.’

[…]

We who live in Ontillu village believe that long, long ago, about three decades ago, there lived in our village a sixty-year-old farmer by the name of Bakkireddy and that he lived an honest and righteous life cultivating his five acres of land and that the land had to be sold off in auction to pay the debts he incurred trying to save it from drought and that on a rainy night he died from sheer fatigue while tilling the fields that were no longer his and that the Five Elements made a covenant with him that the land would never be cultivated by anyone else ever and that over the years a thicket of trees had grown up in the land and had become known as Bakkireddy Thicket. Some of us learned this legend from our fathers and mothers. Some of us witnessed it ourselves when we were children and remember it still. Of course, there are people who doubt the truth of the story, but there are quite as many who think it was a divine occurrence and stand reverently by it as truth. But, whether one is a believer or not, the Bakkireddy Thicket is a landmark in the history and geography of the village. And anyone entering the village from the west would always find himself taking off his turban and dipping his head as he passes Bakkireddy Thicket.

Kesava Reddy, a dermatologist by profession, has several published novellas to his credit. Basing the narrative on his own family history, he has authored as well as translated his novella.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.