To Be or Not to Be: Olympics No Hamlet for Cricket | Outside Edge

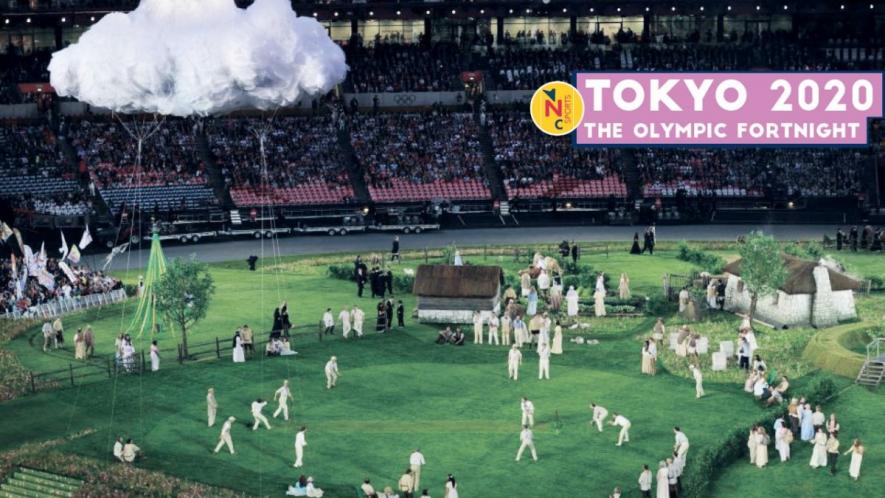

The closest cricket has come being part of the Olympics in over a century is when it was included in the 2012 London Games opening ceremony.

Try imagining cricket being played at the Olympic Games. Avoid taking substances to aid creativity. It is hard, right? This might help. A team from Great Britain wins gold, beating a side from France in a nail biting two-day match. This is no fiction or smoke-screened fantasy. It happened at the 1900 Games in Paris though the competition itself — cricket’s only tryst at the Olympics — had just two teams. Also, France (French Athletic Club Union) were represented by British expats, and the British side (Devon and Somerset Wanderers) had no First Class cricketers in the mix, barring two small-time club players. So why didn’t the fancied game of the world’s biggest imperial power of the time find any takers at the Olympics? Perhaps it had something to do with the fact that cricket was the master’s game in the colonies, to be awed at but not be touched. The snooty nature of the game and the Lords who played it never quite gelled with the ideals propagated by a French Baron and the Olympic movement he and likeminded gentlemen of the time began. No one touched cricket, the Olympics just followed what was in vogue.

Cricket still remains untouchable, played seriously by a handful of countries, and is yet to even become a peripheral blip in the Olympic radar which scans for prospective inclusions every cycle. It has a bit to do with the reach of the game, a small technicality which the International Olympic Committee (IOC) is very strict about. How strange!

Click | For more stories/videos from ‘Tokyo 2020, The Olympic Fortnight’ series by Newsclick

Cricket, admittedly, has grown since Paris 1900 — from two nations, we have 20-odd playing, give or take a few (sarcasm intended). And, 20 is just about the number of nations who have any chance of playing an ICC major event. It is not exactly a global phenomenon. And, the attitude of the governing bodies, and those of the players, are not exactly helping the game’s cause either. Cricket seems to be living in a sense of grandeur like erstwhile rulers following assimilation into an existence in electoral democracy. Across the cricket playing world, it is understood that an inclusion into the Olympic programme will raise the game’s stature. It would also bring in some much-needed aid from the IOC development funds for the smaller nations across the world — unlike the exclusive development idea of the International Cricket Council (ICC) in select pockets. However, that understanding has failed to translate into meaningful measures to push the game into an Olympic-friendly existence. And the blame for that reluctance, inertia rather, squarely falls on the neo-imperialists of cricket, India; and partly on the erstwhile royalty, England.

While the reluctance stemming from self-importance is more than a century old, the biggest damage to cricket’s cause with the Olympic movement was dealt in the 1990s. It was around the time the game’s economy began its journey towards the multi-billion dollar enterprise it is now, powered mostly by the Indian subcontinent. It was a period when the Olympics were also looking at new events and new colours to reinvent itself for the times. It was a prime period for both parties to try and piggyback each other for a larger purpose — the IOC to tap into an expanding, liberalised Indian market, and cricket to get a foothold on the global sportscape.

Needless to say, our cricket stars, and the Boards, had other ideas and priorities in mind. That self-serving attitude continues even now, two decades into the 21st century.

In the past few months, the most critically inclined among cricket fans, who could look beyond the hyped up personas of cricketers, have spoken at large about how Indian stars seldom react or take a responsible stance on social, economic and political matters. It was evident during the violence unleashed on students at JNU and Jamia, and during the Delhi Pogrom earlier this year. It has been all the more glaring with the onset of the pandemic.

To be fair in this debate, there should, and there were arguments in favour of the athletes too. The political leanings of those at the helm of the Board of Control for Cricket in India (BCCI) has put an unofficial gag on the cricketers, some said. Many others presented the frivolous case that a sportsperson’s scope to stand up for what is right should be confined to his area of expertise — the playing field and related matters. Michael Holding would differ, but they were, obviously, referring to Sachin Tendulkars and Virat Kohlis and not woke black icons.

Also Read | Bajrang Punia’s Coach to Return to India on July 30

Let us, for a change, subscribe to that argument, shallow or not. Let the Boards, the ICC and the superstars stick to the game, and do justice to its cause. Here comes the surprise, or maybe there is nothing surprising about it after all. The larger cause of the global development of the game is not exactly a top agenda for the big boys either. And, from the 1990s, the attempt, led by the BCCI and the England and Wales Cricket Board (ECB), has been to create exclusive boys clubs within the cricketing world, compromising ideas of global expansion, and damaging the case (if indeed there was one) for inclusion in the Olympic movement.

The year was 1998. Cricket, the 50-over format, was included in the programme for the Commonwealth Games (CWG) for the first time. Now, imagine that. The CWG, the sporting festival of British imperial history, had not included cricket in its fold so far. Perhaps Kuala Lumpur in 1998 was a start, one thought, though at that point, being a wrestler, I was pretty miffed that the silly game’s inclusion came at the expense of my sport. It seems many in the Indian contingent were upset too with the presence of cricketing prima donnas in the Games accommodation.

When Marcos Bristow, who was part of the Indian badminton men’s team which won a medal at the CWG, came back from KL, he visited the ground in Fort Kochi which we shared for conditioning training. He showed us a picture of him with Tendulkar — his trophy from the Games — but not the silver medal he had won. That shows the power the cricketers wielded in an Indian contingent that included sporting colossus such as Dhanraj Pillay and Pullela Gopichand among others.

That photograph was perhaps a chance occurrence. Apparently, the cricketers hardly mixed with other athletes, and never showed up for any of the other disciplines to cheer the Indians (so much for team spirit). It seems the cricketers did not turn up for their own games too, as shown by the poor results. I remember reading about the detachment shown by cricketers in an article which quoted Indian hockey coach MK Kaushik at the time. The presence of India’s star cricketers, in fact, took the attention from some very notable performances by other athletes.

Those complaints apart, one can never forgive the insulting manner with which the BCCI and the English cricket establishment viewed the entire exercise. They could have been more inclusive and enthusiastic and cited the success in the CWG as a measure of their worth for the Olympics. Over the next decade, with the advent of the shorter, and more exciting Twenty20 format, the bid may even have gathered momentum.

Instead, the Indians played the role of reluctant parties in the Malaysian capital while England decided not to be part of it at all. India sent a weakened side, reserving its main players for the more lucrative Sahara Cup against Pakistan in Toronto, scheduled around the same time. England did not send a team, citing a clash with the County Championship season.

Also Read | London Eye: India’s Greatest Olympic Fortnight

Of course, India, led by Ajay Jadeja, with superstar Tendulkar, Anil Kumble, VVS Laxman and a young Harbhajan Singh in the roster, had some talent in the squad. But that remained just on paper as the players themselves showed little sign of being motivated to gun for a medal in KL. They failed to reach the semifinals, with conspiracy theories doing the rounds that they wanted to cut short the stay at the CWG so that they could travel to Canada for the engagement with arch rivals Pakistan, who, being in a better state than what they are now, also fielded a below par side.

A few years after the missed CWG bus, the ICC woke up to the possibilities that would open with an Olympic inclusion. Realising the work that is needed to make a bid, they were banking on support from India — an economic goldmine that no sporting entity could ignore, not even the IOC.

The BCCI was reluctant. Among the many reasons was a fear of losing its autonomy. An Olympic inclusion means adhering to certain norms that the IOC has set for national governing bodies. The Board, until recently, was also reluctant to get the players adhere to the anti-doping protocols set by the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) and the Indian National Anti Doping Agency (NADA). Again a prerequisite for the Olympic programme. The BCCI argued that it had its own drug and anti-corruption protocols and did not want any interference from an external agency.

The BCCI’s protocols regarding drug testing might indeed be great, if not greater than that of WADA’s. But, a reluctance to partner with a global anti-doping agency also raises red flags. Perhaps there are skeletons the Board wants to keep safe within coffins locked by its own protocols. That stance has eased off a wee bit in the last three years. The BCCI has signed an agreement with WADA, and as if on cue, players have started getting caught in the anti-doping net (the most high profile case so far being that of Prithvi Shaw last year).

Also Read | Tokyo 2020: The Games That Begin Today, Next Year

Be it a bone of contention over anti-doping protocols, or the idea of good governance, global reach or gender parity (a prerequisite for any sport in the Olympic fold), cricket has fallen short on almost all the parameters. A re-energised push has begun. But it happens to be rather late in the day, and just as it was in 1998, a bit shoddy too.

Women’s cricket is included in the programme for the Commonwealth Games in 2022 in Birmingham. Now the question is, why not the men? It is a given that the men’s game has more takers than the women’s, even in India. The practical move, if the game was serious about inclusion in multi-sport events, would be to have a programme for both men and women, so that gender parity is maintained while eyeballs are garnered too. Apparently, calendars and tour commitments were of a bigger priority of the Boards yet again. And the women, who get a very miniscule share of the calendar in any case, were free to feature in the tournament. The move almost sounds like an obligation more than a solid step towards the Olympics.

Now, with more clarity on the situation, let us try imagining cricket at the Olympic Games again. We may indeed need some kind of psychotropic boost to conjure up that vision, won’t we!

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.