How Secular are Indian Schools in Practice?

A teacher and her students in a primary school in Chennai, India. Credit: GPE/Deepa Srikantaiah

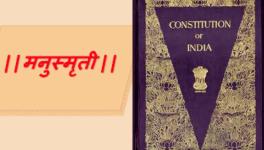

Like many secular nations, India had its challenges in deciding the place of religion within its education system. After independence, Indian secularism aimed to separate religion from State. However, the Indian variant of secularism retained a complex and “multi-value” laden character. This complexity gets reflected in the education system, partly because of the State’s position and partially considering demands of effective learning.

In his book, Social Character of Learning, former National Council of Educational Research and Training (NCERT) director Prof Krishna Kumar discusses how the education system is intertwined with the social identity of a student. Bringing the learners’ home and community values into the classroom has a constructive role in learning.

Educational policies in India recognise the relationship between education and community experiences, which explains the emphasis on culture in classrooms. The National Curriculum Frameworks (2000, 2005) and the National Education Policy (2020) acknowledge and endorse respect for all religions and speak of inculcating awareness about different faiths among students. The institution of District Primary Education Programme (DPEP), the School Management Committees (SMC), and several other programmes have a similar aim: to include the participation of and sensitivity to local conditions in the school curriculum. Such a learning atmosphere in schools has two overlapping functions. One, giving examples of students’ real-life experiences creates a stronger base for their conceptual understanding. The result is improved cognitive growth. Two, bringing the students’ community experiences to the class also communicates that they are welcome in the classroom with their entire being, not just for their calculative brains. This aids engagement in the learning process without fear or apprehension.

A fearless and secure learning atmosphere facilitates the strengthening of neural networks formed due to learning. The background experiences, in this sense, enrich learning rather than disrupt or disturb the education process. Going by the same rationale, countries such as Spain, Ireland, and Sweden teach religious values and morals or comparative religions within their secular curricula. Going a step ahead, Spain accommodates children without restricting religious attire or symbols within public schools.

An educational system that attempts to denigrate and exclude socio-cultural or religious symbols from schools portrays minority cultures as deficient, inferior or substandard. This exclusion inflicts psychic violence on the minority groups, limiting their access to learning. In doing this, the education system that intends to reform the marginalised communities ends up pushing them further away by damaging their sense of self. The United States and France are two good examples of this. Although both countries aimed at total separation of religion from education, researchers have found religious values and symbols are visible within their schools. It has also been found that schools do not object to such infiltrations by students who belong to majority groups.

This is also true for India. Religion has been found to be an integral part of state-funded schools in the country. It is seen in several symbols such as pictures or idols of deities such as Saraswati, Ganesha, and the gurus of various sects used to decorate the administrative offices, classrooms, even principals’ rooms. A closer examination and description of day-to-day practices would easily reveal many instances where religious values and eating habits manifest in the school culture. At the beginning of any cultural festival or school event, we find elaborate rituals such as lighting the lamp, poojas, and reciting the Saraswati Vandana and Ganesha stuti are familiar sights. There are long designated vacations and breaks for specific religious festivals such as Dusshera or Diwali.

Teachers, who serve as role models, also embody and profess the religion they are born into. The ubiquitous presence of religious symbols within Indian education is normalised, unnoticed and unquestioned. Such symbolism is not unusual for students from the dominant or majority groups, as their daily lives outside the school are also marked by similar religious values. However, for students belonging to minority or marginalised communities, the display of such symbols and values results in alienation.

Schools are mini-societies where students are trained to be part of a future society. A democratic structure in the rhythm of a school prepares them for their future citizenship roles. Suppose a school or college, as a reformative unit, communicates that only certain community practices are welcome. In that case, the teachers will establish and reinforce these religious hierarchies in their engagements with teachers, each other, and the students. The students who live these narratives of cultural and religious supremacy will surely reflect that as citizens in the future.

Most importantly, members of communities who live in a miasma of cultural subordination during their student days will grow up feeling desolate as adults and later. In a futile way, the members of a minority or marginalised community will always get blamed for being reluctant to “grow” and unable to access mainstream life. Furthermore, education of the exclusive kind will only instil hostility between communities instead of teaching harmony.

Shaima Amatullah is a research scholar working on the identity negotiations of Muslim students in educational spaces in Bangalore. Shalini Dixit is an assistant professor at the National Institute of Advanced Studies, Bangalore. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.