New Study Suggests Pork and Beef were the Gastronomical Delights of Harappan People

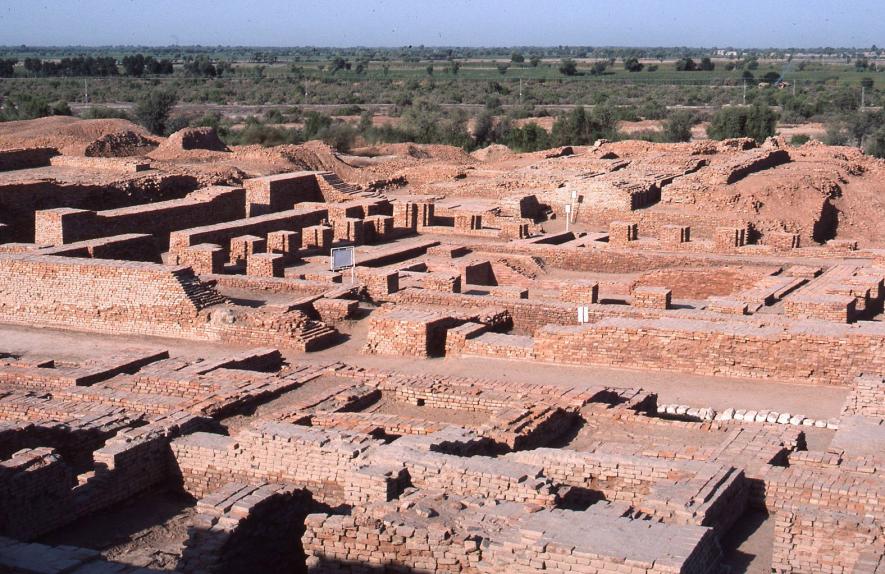

Rakhigarhi. | Image Courtesy: archeology.wiki

What did the ancient Harappans eat at the zenith of their civilisation, some 4,000 years ago? Were the ancient South Asian people vegetarian?

A recent paper published in the Journal of Archaeological Science co-authored by Dr. Akshyeta Suryanarayan, former PhD student at the Department of Archaeology, University of Cambridge, gives us some clues. Dr Suryanarayan and her team extracted and analysed lipid (organic compounds such as fatty acids or their derivatives) residues absorbed in 172 ceramic pottery fragments recovered from the rural and urban archaeological sites of the Harappan Civilisation in northwest India. Lipids extracted from these pots give us direct evidence of the predominance of animal products in the vessels.

“Our study of lipid residues in Indus pottery shows a dominance of animal products in vessels, such as the meat of non-ruminant animals like pigs, ruminant animals like cattle or buffalo and sheep or goat, as well as dairy products,” Suryanarayan said.

Representational image of Harappan pottery fragments (Image credit: Pottery and tc tile from Kanri Buthi, Harappa.com)

The origin of the Harappan Civilisation can be traced back to the site of Mehrgarh in Pakistan dated to about 7000 BCE. The Early Harappan Period is characterised by the establishment of the first urban centres dating to around 2800 BCE. The civilisation reached its peak around 2600 BCE and it went into decline around 1900 BCE.

During its peak, the Harappans dominated a land area larger than either ancient Egypt or Mesopotamia, covering much of today’s Pakistan, most of northwest and western India and as far East as the suburbs of New Delhi. While the mature Harappan Civilisation flourished in a well-defined geographical area during the mid-third millennium BCE, there were contemporary agro-pastoral cultures to the east and south of this area.

Economically, the Harappan people were connected with regions to their west, in Baluchistan and the Iranian plateau, through long-standing communications and trading links. Even at the beginning of the Mature Harappan period, at around 2400 BCE, the Harappans sailed all the way to Mesopotamia to trade with the Sumerians and Akkadians.

The two best-known excavated cities of this culture are Harappa and Mohenjodaro, thought to have once had populations of between 40,000-50,000 people each. Subsequent surveys and excavations in Western India and Pakistan have uncovered more than 1,500 additional settlements. India alone is home to more than 900 sites which are spread across various states, such as Rajasthan, Gujarat, Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Punjab and Maharashtra.

Dr. Suryanarayan and her colleagues selected Rakhigarhi, Farmana, Masudpur, Lohari Ragho, Khanak and Alamgirpur sites to collect the ceramic vessels. All these sites are in present-day Haryana and Uttar Pradesh. The ceramic vessels of the Mature Harappan period (2600 BCE –1900 BCE) were used to collect invisible organic residues preserved in vessel walls.

Lipid residues are relatively less prone to degradation and have been discovered in pottery from archaeological artifacts around the world. Pottery fragments were generally selected from contexts that had radiocarbon dates associated with them. During the Mature Harappan period, Rakhigarhi was a big city and Farmana was a town. Rest of the sites were villages. The wide range of sites gives an insight into the food habits of ancient South Asian urban and rural population.

Extent of Indus settlements with cities in black and study sites in red

The ancient Mesopotamian Civilisation with whom the Harappans had trade links enjoyed a diet of fruits and vegetables as well as fish from the streams and rivers, along with livestock from their pens. Livestock included goats, pigs, and sheep. They would have augmented this diet through hunting game such as deer, gazelle and birds. The chief grain crop in Mesopotamia was barley.

We know from previous research that the Harappans in the urban period had a varied diet principally based on wheat, barley, millets along with meat from cattle, sheep and goat. Over a hundred years of excavations at many sites of the Harappan Civilisation region indicate that they grew cereals, lentils, and other pulses (peas, chickpeas, green gram, and black gram), oil seeds and fruits. Their main staples were wheat and barley, which were presumably made into bread and perhaps also cooked with water as a gruel or porridge. In some places, they cultivated several varieties of native millet. They also ate fish and shellfish from the rivers and the sea –as confirmed by the many bones from marine fish which were found at the Harappan excavation sites.

Based on the analysis of skeletal remains, several previous studies had suggested that cattle and water-buffalo served as the source of their dietary meat and dairy products, while their hides were used for various other purposes. Harappans also kept sheep and goats and hunted a wide range of wild animals such as deer, antelopes and wild boar.

“On the average, about 80% of the faunal assemblage from various Indus sites belongs to domestic animal species. Out of the domestic animals, cattle/buffalo are the most abundant, averaging between 50 and 60% of the animal bones found, with sheep/goat accounting for 10% of animal remains,” an earlier study had found. “The high proportions of cattle bones may suggest a cultural preference for beef consumption across Indus populations, supplemented by the consumption of mutton/lamb,” it stated.

Also see: Indus Valley Civilisation: Where Did Agriculture Come From?

The study of the residues inside the ceramic vessels recovered from the Harappan sites further substantiates the assumption that consumption of beef, goat, sheep and pig had been widespread. “This study is unique in the sense that it had a chance to look at the contents of the vessels. Normally there would be access to seeds or plant remains. But through the lipid residue analysis, we can confidently ascertain that consumption of beef, goat, sheep and pig was widespread, and especially of beef,’’ Suryanarayan was quoted as saying in The Indian Express.

Broad similarity in products is observed across both rural and urban sites, possibly indicating a degree of regional culinary unity. While people living across rural and urban Indus sites in northwest India used different types of material culture and pottery, they may have shared cooking practices and ways of preparing foodstuffs.

Though pigs make up about 2–3% of total faunal assemblages from the study sites, nearly 60% of the vessels analysed for lipid, contained remnants of non-ruminant animals. Contrary to faunal evidence, a dominance of non-ruminant fats in the vessels is startling. Incomplete recovery practices of small bones of pigs or birds from the archaeological sites may be a reason behind the gap in high percentage of non-ruminant fats found in the ceramic pots and modest number of pig skeletal fragments collected from different sites.

Limited evidence of dairy processing in Harappan vessels from northwest India is noteworthy. “It is possible that dairy consumption was limited to fewer groups, was not as widely practiced in these Indus settlements, or that dairy products were primarily used in vessels not analysed in this study, or used in vessels made from organic materials that have not survived.” the study noted. The relatively large sample size of vessels analysed in this study provides some confidence that the findings provide a reasonable reflection of reality in the Harappan civilisation.

Earlier this year, from February 19 to 25, the National Museum in Delhi arranged a specially crafted tasting menu on Harappan food culture called ‘Historical Gastronomica - The Indus Dining Experience’. It included Khatti dal, Kachriki sabzi, black gram stewed with jaggery and sesame oil, raggi ladu, thin barley griddle cakes, sweet rice with banana and honey and a special ‘Indus Valley Khichri’.

However, at the last minute, the organisers removed the non-vegetarian options from its menu, which included meat fat soup, quail roasted in Saal patta and salt cured sheep. The event was jointly organised by the National Museum, the Ministry of Culture and a private firm. The Additional Director General Subrata Nath had told ANI, “Their Harappan menu is very well researched but they should not have opted for the non-veg dishes,” adding, “In any case, we had a discussion and were able to avoid just in time what could have become an embarrassment.”

But, meat dishes were not really an embarrassment for the Harappans. In the face of mounting scientific evidence that this was a meat-eating society, there is a need to reconsider the views of what they might have been embarrassed by. They ate meat whenever they could, like any other people of the middle Bronze Age in Central, Middle and South Asia.

(The author is a former Associate Professor of Jadavpur University and a writer. The views are personal.)

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.