‘Political Abuse of Buddhism no Different from that of Hinduism, Islam or Christianity’—Jairam Ramesh

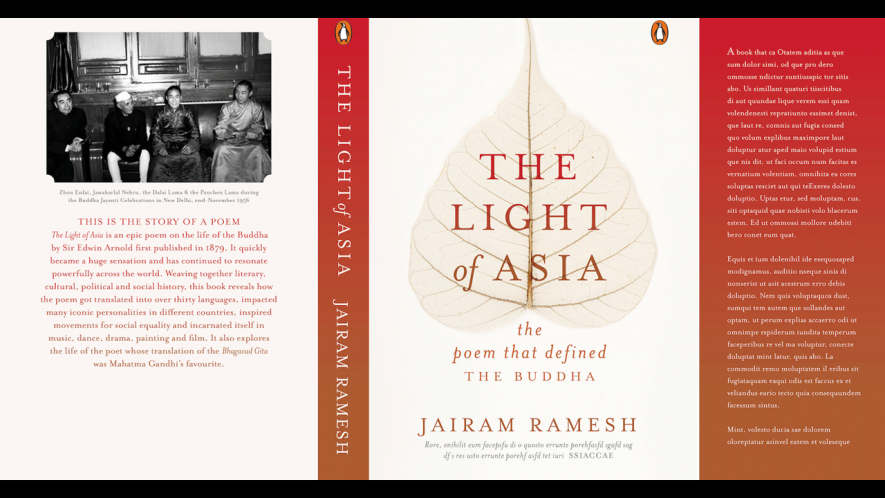

Image Courtesy: Penguin India

Senior Congress party leader, former Union minister and the author of several books, Jairam Ramesh, has picked an unexpected theme for his latest work, the 1879 epic poem, The Light of Asia: The Poem that Defined the Buddha and its British author, Edwin Arnold. The book contributed to making Buddhism popular again around the world after its decline in India centuries ago. Ramesh’s last book, A Chequered Brilliance, won the prestigious Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay award in 2020. In this email interview with Rashme Sehgal, he fields questions on the relevance of The Light of Asia, contemporary Buddhism, and the crisis in his party.

An epic poem on Gautama Buddha written by the Englishman Sir Edwin Arnold, who spent a very short period in India... How did you come to choose this surprising topic for your book?

Edwin Arnold spent around 26 months in India between December 1857 and early 1860 but became conversant in Sanskrit and, probably, Marathi. He had translated the Hitopadesha and the Gitagovinda before he wrote his epic poem on the life of the Buddha, and that first came out in mid-1879. It is actually not that surprising, because there was a generation of Englishmen in the late Victorian era, who, while being great supporters of the British Raj in the subcontinent, were enamoured and captivated by various aspects of Indic civilisation—its literature, poetry, drama, philosophical traditions, spiritual legacies, art and architecture and music. Sir Edwin was very much part of this quite remarkable generation.

The rather romantic Victorian-style The Light of Asia is hardly a classic, yet it enjoyed tremendous popularity. What explains this?

There was a growing appetite for a Buddha-like figure, a figure who stood for a system of personal ethics and morality without claiming any divinity, a figure who stood for a personal search for the truth and understanding without imposing dogma of any kind. Buddha gained popularity because he was seen as a pre-Christ Christ-like figure who was not associated with any organisation like the Papacy or the Church.

Remember that the late 19th century was also a period of growing economic prosperity in the West and therefore also when people were looking for things that could give them an anchor and solace. It was a period of growing doubt in organised Christianity based on the Bible, which was being debunked by rapid scientific advances in geology and other areas. Darwin’s revolutionary book had appeared exactly twenty years earlier than Sir Edwin’s epic poem and it had completely transformed Victorian society. From England, the influence of the poem spread to Europe and America and soon thereafter to Asia including the Indian subcontinent.

The Light of Asia influenced Vivekananda, Rabindranath Tagore, Mahatma Gandhi and Ambedkar, to name a few. And yet Buddhism does not enjoy popularity, conceptually or in the popular consciousness, in the subcontinent as it does in South Asian countries. Why?

By the seventh or eighth century CE, Buddhism had gone into decline in India. Buddha had been appropriated as the ninth avatar of Vishnu. It lost out to aggressive Brahmanical forces first and thereafter was delivered the final blow by Afghan conquerors who themselves came from Buddhist traditions but had embraced Islam. I should add that I am not a student of Buddhist history and the practice of Buddhism carried the source of its later decline within it.

Buddhism survived of course, in Ceylon, which later came to be known as Sri Lanka, in the Chittagong Hill Tracts in today’s Bangladesh and Lahaul Spiti and Ladakh in India. But there is no question that for over five hundred years at least, the Buddhist faith was the predominant one in India. It is because it was seen as the greatest threat that the Brahmins appropriated him as an avatar of Vishnu—they did not do this in the case of Mahavira, for instance.

A right-wing Hindu ideology is sweeping through the country under the current political dispensation. How are the Buddha and Buddhism relevant to politics today? Was not BR Ambedkar the last prominent leader who adopted Buddhism and captured the imagination of the public?

Gandhi, Tagore, Nehru and others were whom I call philosophical or spiritual or cultural Buddhists. Ambedkar, on the other hand, saw Buddha as a political revolutionary who challenged Vedic and Brahmanical orthodoxy and prejudices. In this, he was following in the tradition of social reformers in what was then Travancore, such as Sree Narayana Guru, and in what was then the Madras Presidency, such as Iyothee Thass. There is also strong evidence that Dr Ambedkar’s views on why Siddhartha gave up his princely life were shaped by his reading of Dharmanand Kosambi, the great scholar of Pali. Incidentally, Vivekananda saw Buddha as a Vedantist reformer.

You mention in your book the great controversy over Bodh Gaya between the Hindus and the Buddhists, from 1886 to 1953. You write that Arnold’s visit in 1886 to Bodh Gaya triggered this dispute. He wrote that “the Mecca and Jerusalem of Buddhism” was being desecrated by a Shaivite mahant who had taken over the Mahabodhi temple. Can you elaborate on this controversy?

I have a lengthy chapter on this and it has to be read to understand the background to the controversy over the Mahabodhi Temple at Bodh Gaya. I will only say this much: the agitation for Buddhist control over the Temple, which has in its close precincts the place of Siddhartha’s enlightenment when he became the Buddha, began with Sir Edwin’s visit there in February 1886. He described in newspaper articles and later in a book how anguished he felt when he saw how the “Mecca of Buddhism” (and those are his words) was being desecrated by the Shivite Mahants.

He went to Ceylon after this visit to Bodh Gaya and described what he saw at the Mahabodhi Temple to a very respected Ceylonese Buddhist monk-scholar who, in turn, gave Sir Edwin the idea that the larger Asian Buddhist community should have the responsibility for managing the Temple. A campaign in support of this idea was launched by Sir Edwin and spearheaded by another great Sri Lankan monk-scholar, Anagarika Dharmapala.

To cut a long and convoluted story short, the matter was finally resolved sixty-seven years later. The resolution has held firm since May 1953 and when the transfer of the Mahabodhi Temple from the control of the Shivite Mahant to a Board comprising of an equal number of Hindus and Buddhists took place, verses from The Light of Asia were recited. Negotiations between the Hindu Mahasabha and other such organisations on the one side and the Mahabodhi Society on the other took place for years under the inspiration of Gandhi and with the active participation of Rajendra Prasad, Sri Krishna Sinha and other leaders of the Indian National Congress in Bihar. Nehru, too, was closely involved, particularly in the 1947-49 period.

Would you say the Light of Asia is more about Buddha’s life and less about his philosophy? How was it received in the largely Buddhist countries, such as Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand and Cambodia?

Yes, the epic poem is all about Buddha’s humanity and not his divinity. This is what made it a sensation and gave it the popular appeal it had across continents, an appeal that endured for decades. It got translated into twelve European languages, eight Northeast and Southeast Asian languages and twelve South Asian languages. It had a phenomenal impact on what was then called Siam (today’s Thailand) and Ceylon [Sri Lanka]. It is recalled even today in Sri Lanka. There is an annual elocution contest conducted in Colombo called ‘The Light of Asia Contest’ in which schoolchildren are judged for their elocution skills based on their recitation of its verses.

Earlier, Indian leaders were drawn to the Buddha as a cultural figure, but would you say Buddhism and the Buddha have been put to rather potent political use?

I think the political abuse of Buddhism is no different from the political abuse of Hinduism, Islam or Christianity. It is a sad reality that countries that swear by the Buddha have seen social strife and ethnic conflicts and political mobilisation has taken place using Buddhism as an instrument. Japan went to war in the early 1940s calling itself “the Light of Asia”. The Sri Lankan Prime Minister SWRD Bandaranaike was assassinated in 1959 by a Buddhist monk. Look what is happening in Myanmar now.

Interestingly, you note how western women have supported spiritual figures such as Vivekananda and Angarika Dharmapala. How would you explain this?

Very wealthy Western women were drawn to charismatic and eloquent spiritual figures such as Vivekananda and Dharmapala, because, I think, they were searching for something more meaningful than their societies could provide. Mary Foster [the first Hawaiian Buddhist and a philanthropist] was a great benefactor of the Mahabodhi Society in what was then called Calcutta, which is not generally known to people in India. She made possible much of Dharmapala’s campaigns to restore the Mahabodhi Temple at Bodh Gaya and restore Sarnath. Of course, we know more of the role that [American writer and philanthropist] Sara Chapman Bull and Josephine MacLeod [an American indophile] played in Vivekananda’s life, apart from Margaret Noble, [an Irish teacher, social activist and disciple of Vivekananda] who became Sister Nivedita.

During your research into Victorian England, what did you learn about British attitudes towards Indians?

This may not be to the liking of many, but I do believe there were Britishers who, while being staunch defenders of colonial rule in India, also became great scholars of India in different fields. And I do not think they became aficionados and scholars of India to justify British rule. To see in whatever they did a subconscious effort to keep India in a state of permanent political subjugation is being churlish. I am a great admirer of Edward Said—the scholar and the human being. But he, unfortunately, gave Orientalism a terrible meaning and reputation with his book, which has blinded us to this generation of Britishers who were genuinely taken up with Indian culture in myriad ways.

I should add that in their discovery of this Indian culture they [British scholars] were helped not only by other Europeans but perhaps more importantly by a number of Indians. Now, one could argue that these Indian interlocutors were almost always Brahmin, and that is indeed true.

But I am not justifying the politics of people like Sir Edwin Arnold. I am only saying that they became great popularisers of the rich legacy of Indic civilisation—and I use the word Indic advisedly. Gandhi’s introduction to the Bhagavad Gita came from Sir Edwin’s translation, The Song Celestial, which remained one of his favourite books till the end of his life

In your view, was the author of The Light of Asia an unabashed Victorian imperialist?

Yes, he was an unabashed imperialist who did write, though, that at some point in time British rule would have to come to an end. He, however, left the time undefined. He was a great admirer of Dalhousie and Curzon. But, curiously, I should also point out that he was a defender of Sati and very critical of the laws passed to end it. He saw in it love and chastity and fidelity and nobility. He also drew parallels to it in ancient Roman society.

Now can we turn to your party, the Congress? After a string of electoral defeats, why is the leadership issue still unresolved? More crucial state elections are around the corner...

We have a full-time, hands-on Congress president who admittedly came back to that position at the request of the Congress Working Committee but on an interim basis. So, there is no vacuum. Preparations for the forthcoming elections are well underway. The election process for a regular Congress president was originally scheduled to have been completed by end-June 2021, but this was before the country was overwhelmed by the second wave of Covid-19 on account of the hubris and mismanagement of the Modi sarkar.

I am sure a new schedule will be firmed up once vaccination reaches a decent level at least. Let me remind you that even though we did not form the government in Assam and Kerala, which we should have, the difference in vote share between us and the BJP in Assam and between us and the LDF in Kerala was very, very small.

Several prominent Congress leaders have deserted the party, affecting morale. They perhaps felt they would gain from joining the BJP rather than staying on with the Congress unless its political fortunes revive?

The desertions reveal more of the deserters than the place they are abandoning. Each of the deserters has got much from the Congress—in many cases, much more than they deserved. They can say whatever they want, but the fact remains that they have left in search of the perks of being in power. They have revealed their true colours.

You once said Atal Behari Vajpayee was a vegetarian opponent in comparison to the barrage of problems your party has faced during the Modi dispensation. Is that not all the more reason to put your house in order?

Mr Vajpayee was more accommodative and responsive to what the Opposition was saying. He did not rule through FDI—fear, divisiveness and intimidation. Mr Modi is his polar opposite—more ruthless and remorseless, more vindictive and more self-obsessed. It is certainly more challenging to deal with him—with both the substance and style of his governance. We are well aware of it.

The BJP has handled the economy and the Covid crisis poorly. Yet people feel the Congress party has not capitalised on such issues. Why is your party finding it so difficult to go to the streets rather than to tweet?

It is simply not true to say that the Congress party has not taken up issues of public concern. We have done so both in Parliament and outside. Covid-related restrictions have hampered agitational activity to some extent, but even so, in many states, our public outreach activities have proceeded apace. I think Congress-bashing has become a favourite pastime not only for Modibhakts but also for those opposed to him. Running down the Congress day in and day out serves no purpose.

(Rashme Sehgal is an independent journalist.)

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.