‘Sooner the Taliban are Helped to Stabilise Afghanistan, the Better for India and the West’—Adrian Levy

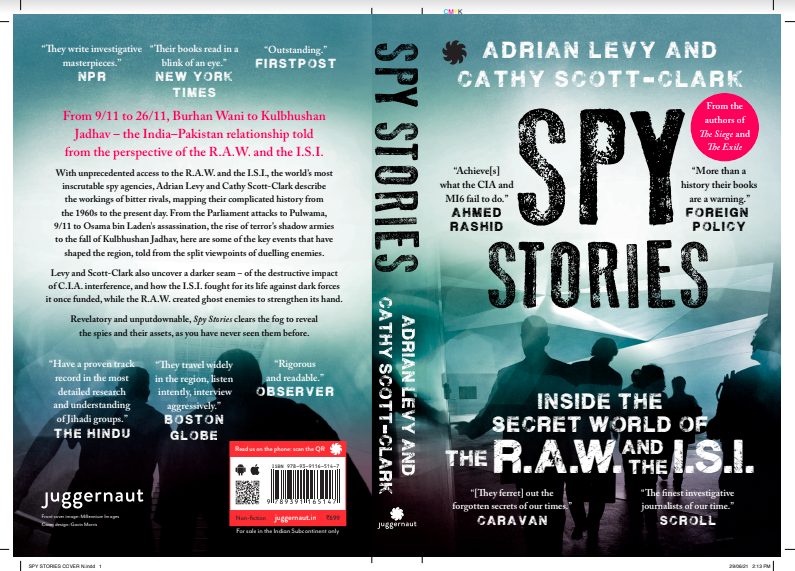

Kabul’s fall was not a Taliban victory but a pragmatic recognition by the peoples of Afghanistan of the inherent weakness of what the United States had raised and then abandoned there, well-known writer Adrian Levy tells Newsclick. Levy and co-author Cathy Scott-Clark have written a series of best-sellers on the 26/11 attack in Mumbai, the lead up to the arrest of Osama bin Laden, the proliferation of nuclear weapons in South Asia and ‘The Meadow’, an acclaimed book on the events surrounding the kidnapping of five tourists in Kashmir in 1995. Their latest book, ‘Spy Stories: Inside the Secret World of the RAW and the ISI’, describes the cloak-and-dagger world of espionage. Edited excerpts from an email interview with Rashme Sehgal.

Adrian Levy and Cathy Scott-Clark

Is the Taliban takeover in Afghanistan really a big success for the ISI? How will it impact India?

Let us be clear and try to see beyond the horizon: the ISI did not win. The United States and the Bush-Cheney war on terror floundered spectacularly, and grimly, with almost one million deaths and $8 trillion spent over two decades of supposedly fighting terrorism. Instead, a broadside to the murderous 9/11 attacks became a fight with an outfit that did not plan them—the Taliban. Bush-Cheney showed their hand by refusing a 2002 and 2003 Iranian deal to hand over much of the Osama bin Laden family and Al Qaeda military council, held in Baluchistan and Tehran by the Revolutionary Guards.

Instead of a managed peace in Afghanistan and an orchestrated surrender of Al Qaeda that might have started the complex process of normalising relations with Iran, the White House declared an illegal war based on a manufactured premise with Iraq, which also had nothing to do with 9/11. The war spread instability to Libya and Syria and grew a pathological Al Qaeda in Iraq, spawning a craven Islamic State (Daesh) whose Caliphate was far larger and more functional than the Islamic emirate of Afghanistan ever was. Having jeopardised peace in Asia and the Gulf and triggering explosive and horrific backlashes in almost every European capital, where prejudice, racism, exclusion and petty criminality formed new unconnected cells that found cause with Daesh—neither making the world safer nor eradicating terror—[United States President Donald] Trump abandoned his Kurdish allies and [President Joe] Biden let go of the Afghan project, and its cheerleaders ran for Tajikistan.

You would also have to add the rules-bound order as a victim of the Bush-Cheney dumpster fire. The CIA deliberately obscured the plotting of 9/11, with critical details about the transit of two protagonists from Malaysia to California suppressed to nullify the FBI. Soon after, vengeful officers at Langley lobbied the White House and Department of Justice to allow them to recoup their losses and buoy their reputation. Their new ‘gloves off’ plan was to vanish suspects to foreign off-the-books black sites, where they got put through an experiment that two United States presidents would describe as torture. All this happened outside United States jurisdiction, getting around the Geneva Conventions and the post-World War II rules-bound system to prevent carnage of that kind from happening ever again. America and its allies in the United Kingdom, France, Germany and other smaller European powers supported almost all of these actions—as did Pakistan—and are also to blame for the circularity in Kabul; it falling, a mirage rising, and that mirage falling in 2021.

What was Pakistan’s role in this manoeuvring and manipulation?

Pakistan’s role never strayed from its stated position of demanding a government in Kabul that was friendly with Rawalpindi. It openly declared its position from the days after 9/11, to the early (October 2001) ISI missions to see Mullah Omar, to the ISI chief’s first Taliban plan (November 2001), when General Ehsan ul Haq, its director general, put together a coalition of Saudi royals and British Blairites to get Bush-Cheney to induct the Taliban into a new government of national reconciliation in Kabul. It would support the destruction of Al Qaeda, but the Taliban would not be suppressed.

Al Qaeda was eventually massively damaged, and almost every senior leader rousted from Pakistan. They were tortured in CIA black sites, making their prosecutions, based on coerced evidence, impossible, leading to a twenty-year legal farce where Bush’s push for justice would deny that very thing to the families of the 9/11 victims. There is no trial, so evidently, while we know everything there is to know about 9/11—almost—there are no verdicts.

Zoom to 2021, and the United States ran from Afghanistan after Rawalpindi lost a great deal more—48,504 fatalities until 2013 in its internal war against terror and a claimed direct cost from terror to its exchequer (until 2014) of $102.51 billion, none of which is ‘winning’. Along the way, it punished, manipulated and courted Taliban commanders and religious scholars, jailing some, torturing others, and protecting networks allied to Rawalpindi. Internal intelligence from Pakistan and India shows this path was always treacherous for the ISI and Pakistan Special Forces. Their influence was only partial, piecemeal really, and Aabpara (a zone in Rawalpindi) did not have the bandwidth to encompass the regional pan-Afghanistan Taliban while concentrating on the eastern border with India and also attempting to penetrate its border with Iran.

Now that Kabul has fallen and the American mirage of country-wide power is pricked, Pakistan has lots to fear. ISI chief Lt Gen Faiz Hameed was in Kabul to knit various Doha and non-Doha factions into an interim government, but is also fighting his own battle—he hopes to be army chief later this year or next. In Rawalpindi, his outfit is considering an enormous mountain of problems no country envies.

What are these problems?

For example, what kind of international alliance would come to the aid of the new Kabul, and how would an alliance of parties that mistrust each other bind together? China would want to step in and increase its trading options from Central Asia to Gwadar Port, but Saudi Arabia also wants in, and has a problematic relationship with Beijing. The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) also detests Qatar, whose status has been elevated by back-channel work for the Taliban and offering early technical assistance to Kabul to get the city and its airport up and running. Turkey wants in as a Sunni competitor to Saudi, and so does Iran, which opportunistically funded the Taliban. The KSA, Qatar and Turkey cannot contemplate Iranian input into reconstruction, while Iran is thinking of its flailing Indian-backed port in Chabahar, which it hopes will rise with a tentative peace in Afghanistan.

How to graze this monster? How to keep the disparate factional Taliban together? How to transform a movement of mujahideen into technocrats? How to pay for the human catastrophe of the millions fleeing that country into Pakistan. Pakistan’s workload is unenviable. India will, for now, relish its watch-and-wait approach while tentative talks between Delhi and Moscow, and Delhi and the Gulf and Riyadh play out. We don’t know how any of this will go. We only know what everyone fears. However, chaos suits terror, so the sooner the Taliban are helped to stabilise their country, the better for India and the West. Al Qaeda is there but presently cannot attack the West or India in numbers. The anti-India insurgents do have that intention, but we don’t know if the Taliban will allow that or stamp on it too.

What are the significant issues for India after the the US project in Kabul has failed? Some say Islamists in India would feel boosted. Others say Kashmiri youth would be drawn by the Taliban’s success...

These kinds of equations are treacherous as they infer a radical vehemence on a movement that is not, and was never, there. The fall of Kabul, and the rise of black (or white) banners, is inevitable all over the world. These banners rise in support of an Islamic emirate and certainly will rally Islamists. But jihad has, or is, morphing from head-on collisions with the West and the United States into local struggles within oppressive states.

Kashmiri people do not share the goals of the Taliban, nor do they seem to want the kind of emirate the Taliban has in mind in Afghanistan. Kashmir’s grievances are to be dealt with by politicians in Kashmir and Delhi who know only a political fix will work, not further militarisation and more oppression. Al Qaeda never seriously tried to join the Kashmir insurgency, as it knew it would not survive in the Valley. Its constituencies remain in the Sahel, in West and Central Africa, and Syria.

The significant issues raised by the fall of the United States’ project in Kabul are that instability and lawlessness might prevail, inside which anti-India and anti-Western forces can gain traction. Where they strike is anyone’s guess, but to portray Kashmir as an Al Qaeda-style Islamist insurgency is inaccurate and undermines the causes and pushes and pulls that have made the region burn for decades.

Inside the security agencies in Pakistan and India, Kashmir is regarded as a stalemate, a political stand-off, which the [former Pakistan President General Pervez] Musharraf back-channel with India (2004-07), came extraordinarily close to resolving. However, there are forces in Pakistan and India that would like to pretend these talks did not happen and no solution is possible other than militarisation. With grievances left unheard and unresolved inevitably leading to yet another local uprising chaperoned by Pakistan, which will be put down equally bloodily by India, the cycle continues.

By 2010, the number of foreign insurgents entering Kashmir reduced to low double digits. However, five years later, the state was on fire through a combination of military killings, legal impunity for murders and disappearances and widespread use of punitive, extreme crowd control using pellet guns etc. The failure to keep the peace and restore order would lead to suspension of government and the abrogation of Article 370. These are choices made by the security services and the political establishment that hoped for this outcome and wrote about it in its electoral manifestos. Why look for new reasons for Kashmir to fail all over again?

What will India have to do after the Afghan imbroglio?

India has its delicate balancing act to configure. Ever since 9/11, the RAW wanted to smash the ISI pact with Langley, (a colloquial metonym for the CIA). Now that it is all but destroyed and the CIA has become RAW’s closest working partner, what will that reap for India? America acts out of self-interest—see the Kurds and the ANA as only two examples of discarded allies—and this might not be good for India. Will Delhi maintain its national interest and strengthen its institutions or follow Pakistan’s path of ploughing ahead while ignoring mass protests, dismantling democratic institutions along the way? India’s internal authoritarianism—the campaign against journalists, film-makers and social media clients and companies, the communal clashes that have created enormous tensions—increasingly places Delhi at odds with the Biden administration. (Although it, too, is struggling on human rights.)

Can India get what it needs from the United States without triggering conflict elsewhere? Will the United States need for India continue to overlook its domestic stridency, Islamophobic communal tendencies, and stamping down on democracy, in ways that ape [Hungary’s authoritarian Prime Minister Viktor] Orban and [Philippines President Rodrigo] Duterte more than [outgoing German Chancellor Angela] Merkel and [French President Emmanuel] Macron?

Other than its role in the creation of Bangladesh, would you say India’s RAW can rival the ISI? I know you attribute Afghanistan to the abject failure of American policy. Still, the ISI and Pakistan project it as a feather in their cap.

Kabul is not 1971. That is a stretch. Perhaps people use this analogy to quantify the pain shock felt at Kabul’s loss. But East Pakistan ‘belonged’ to Pakistan, in a surreal topographic contract wrought by the British. Losing it was to lose part of Pakistan, as ascribed after Partition. How it was lost left an indelible scar on generations of Pakistan military officers and spies, made to feel inadequate facing a larger skilful military neighbour. The ISI and military would seldom forget and instead became ever more committed to proxy strategies to hurt India.

That loss of a part of Pakistan in 1971 was certainly hastened by extraordinary and daring espionage—covert activities authored by India—that intercepted phones and mail and ran proxy forces that bloodied Pakistan and its allies. And it would be accurate to say that ISI and its covert plays boosted the Taliban, helping it survive the two decades of American nation-building. Still, the ISI did not micro-manage the rise of the Taliban or manipulate decisions in the provinces to back the Taliban over the mirage of Kabul.

Kabul’s fall was not a Taliban victory but a pragmatic recognition by the peoples of Afghanistan and their political leaders throughout the country of the inherent weakness of what the United States had raised and abandoned. The Afghanistan that collapsed was never India’s. Many development projects that India lavished money on never materialised, nor came near to completion.

The loss of Kabul was foreseen since November 2001, when many nations and American officials advised Bush-Cheney not to burn the country down and try to rebuild it. Bush-Cheney immediately brought in the pathological brigands and mass killers the Taliban had routed—making them governors and parliamentarians in a new kind of disguised lawlessness where, on the surface, changes appeared to blossom with the West’s focus drawn to the paved roads of Kabul. In the provinces, the United States enabled the narco-terrorists that the Taliban had quashed to become resurgent. When they grew too powerful, America and its surrogates in the ANA turned on them, too, in campaigns that claimed tens of thousands of lives that never got accounted for.

The ISI feels triumphant in knowing they were right, but RAW’s successes are many and considerable, some incremental and subtle while others stopped history in its tracks. Indian intelligence identified Kahuta, where the Pak enrichment project was housed before the CIA and got inside it. It understood Pakistan’s nuclear readiness well before any other power. RAW got inside Pakistan GHQ computers and exploited a technology lag. The lack of SOPs by even military chiefs in Pakistan led to Indian technical intelligence intercepting Musharraf in China on a hotel landline, debating Kargil with his military chief, exposing the lie that freedom fighters had taken Kargil.

Indian intelligence saved Musharraf’s life, intercepting more plots to kill him, and shepherded his back-channel, which came achingly close to success. Indian intelligence also created the pervasive and useful myth of Pakistan as the terror state, blurring Al Qaeda with Rawalpindi, projecting both as each other’s project, when nothing could be further from the truth.

Indian intelligence is among the best at raising pernicious, improvable allegations that become urban truths, knowing that refuting them looks desperate. So, in many vital ways, the intelligence services succeeded in projecting India and downsizing Pakistan.

Your book describes the shared history of the RAW and ISI. But you allude to how resources allocated to RAW are not equivalent to the resources at the disposal of the ISI. Does this hamper RAW?

Money was a limiting factor for the RAW. Still, much more injurious was the deeply non-aligned and pacifist Indian politics that essentially doubted the value of foreign intelligence and the covert world, broadly seen as anti-democratic, uncontrollable facets of the military, kept at bay by civilians elected to office and civil servants. It changed to a degree by the mid to the end of the 80s, as the RAW continually sounded the alarm over the deepening power and wealth of the ISI, enabled by the CIA and the American secret war in Afghanistan, enriched by opium cash, illicit weapons trading and the siphoning off of US aid.

India’s political establishment finally understood this after the Punjab crisis built throughout the 80s, enshrined in the assassination of Indira Gandhi, and when Kashmir exploded at the end of that decade. These were the over-spills from Afghanistan.

Throughout, RAW was infuriated by its lack of traction in the United States, deftly reaching out to America’s foes in China, Iran and Russia in well-balanced operations. RAW also sought out training from the British in counter-insurgency, seeing how Pakistan had done the same with the growth of the anti-Soviet mujahideen. RAW had its officers trained by the Royal Ulster Constabulary in Northern Ireland and the British security services, given that the region was going through a bloody civil war in which torture, disappearances and cold killings (by the state and its opponents) had become the norm. And these practices, the puppeteering of rebel outfits, the creation of fog, deniable ultra violence would become a standard operating procedure all over India.

After 9/11, the power of Indian intelligence began to grow, and 26/11 triggered the transformation of intelligence in India—in terms of patterns of foreign cooperation but also funding. Interestingly, post 26/11 intelligence would also become far more of a political football, used and abused by parties for their ends and goals. After 26/11, there seemed to be a consensus that given the brazen nature of the attack on Mumbai—a horrific broadside steered by Al Qaeda and Lashkar-e-Taiba, among others—that India needed to be far more proactive. From this date, exhausted and enraged by the forces that had sniped at India, intelligence officers did begin to manufacture conspiracies that augmented those being run by Pakistan, until it was hard to see which side was controlling which terror cells, carrying out which acts.

How is the work culture of the RAW different from that of the ISI?

ISI mocks India’s reluctance to engage but admires India’s handling of its endgame, India’s endurance to follow operations, watching them fall into place with an understanding of how they might climax. RAW belittles ISI for its lack of moral compass and propensity for terror but admires its instincts to engage rapidly, without the baggage of democracy.

ISI is also jealous of India’s international reach and how it tells its story powerfully and with great panache, using skilled diplomats and soft power resources, the sponsored chairs in university departments and the academics placed in think tanks the world over. India tells its story extremely well, and with conviction, ISI feels. Pakistan, they fear, stumbles and does not have the support from the diaspora within academia, industry or governance.

Both organisations, being full-spectrum agencies, also work in the amoral, a-legal sphere, using whatever resources are appropriate in these worlds. Human intelligence involves recruiting assets or compelling informers... Both outfits harvest at the time of emotional exhaustion. After bomb blasts or massacres, intelligence outfits graze, looking for the exhausted and enraged who might come on board. For India, that has meant cozying up to outfits like the MQM in the Pakistan Sindh and using that movement for grassroots intelligence and foment unrest. The same has been done along the Durand Line and in Baluchistan. Pakistan took the lessons of the CIA’s paramilitaries to heart. It augmented hostility to Delhi in every place where it already existed—working India’s fault lines in the Punjab, Northeast and Kashmir, etc. India would do something similar in Kashmir, creating grey forces like the police Special Task Force or Special Operating Group that gained the character of the French Foreign Legion, a place to where officers would go when they ran out of options in the force. Even though it began as a means of getting Kashmiris to own the counter-insurgency, it became chaotic and criminal, accused of rampant murders, rapes, abductions and torture.

Proxy forces like the Ikhwan—insurgents induced into surrendering and working with the Rashtriya Rifles and the Border Security Force—would also become criminal enterprises that robbed and pillaged in ways never conceived but hard to stop. Just as India’s proxies and puppets wreak fear and violence, so would Pakistan’s force multipliers—the Lashkars and their kind. Islamist proxies mentored by Rawalpindi and Aabpara would slip their leash by 2002 and form a new terror amalgam as anti-Pakistan as it detested India.

RAW is crippled by its police structure for recruitment and promotion and has ignored internal calls for a charter and place in the Indian Constitution that guarantees its independence. Without these, it can be used and abused, just as happened to the United States in Iraq and Afghanistan. First, real intelligence was manipulated by politicians to argue for a war in Iraq. Then fake intelligence was handed to politicians who wanted to paint a rosy picture of wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, making it hard to tell what was really going on, giving rise to that most memorable American phrase, the self-licking ice cream cone.

Indian intelligence requires specialisation and reflecting the diverse communities it works in, yet remains a policing outfit run by one faith predominately that shuns Muslims and is sclerotic on caste and gender. Officers want this to change.

Several strategists believe India was caught unawares by developments in Afghanistan. Is Indian intelligence better run today with the BJP in power and Ajit Doval steering the NSA?

The straight answer is all changes are incremental. The RAW is a large vessel, and corrections or reforms come slowly. Post-2001. Post 26-11. Post-2014, and the BJP landslide. We see now the culmination of small changes, which would be a more honest way of seeing it than ascribing them all to one administration. To be honest, anyone who does this is drawing a hagiography.

In Pakistan, you hear ‘Bajwa Doctrine’, a phrase created by the army chief General Qamar Javed Bajwa and his cheerleaders to graft legacy onto his career. Actions that took place when he ran the show—decimation of the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan, Lashkar-e-Jhangvi and the suppression of Jaish, etc.,—were the culmination of work put in place in 2006 and 2007 and picked up by General Ashfaq Parvez Kayani and others.

With Doval’s re-emergence in 2014, a practitioner with many decades in the field came to the fore, who had experienced many creation stories, including Operation Blue Star and after, the rise of the Kashmir wars, the IC814 hijacking, Kargil, and the post 9/11 chaos. The messaging became more focused as India became more assertive. A new national security set-up enabled India’s view—those of the BJP—to be better projected, increasing India’s influence over the global argument.

The government’s story for voters was also streamlined across social media platforms, compliant media outfits, and the movies. Expensive military gestures spoke to the new assertiveness and chauvinism. Surgical strikes and Balakot were fundamentally unknowable operations aimed at voters far more than insurgents or their paymasters. Did 300 insurgents die in Balakot? Now we know they did not, but at the time, Doval’s magic saw these kinds of stories amplified globally, in all the right places, and by passive assets, including Western writers happy to ape his story. None of these operations changed ground realities.

Politically, national security management has won the BJP a far greater majority and served to project it as unified in its mission to assert its right to self-defence through offensive non-nuclear action. No underlying crises have been dealt with any better than by any other administration at any other time. Kashmir, for example, remains a time bomb without a political solution. Islamists facing down India flitted to Afghanistan from where they train and indoctrinate new followers and hope to mount attacks. Jaish remains a potent enemy everywhere. The scale of the threat facing India has not diminished. Indian diplomacy [just] works better than in Pakistan at telling the nation’s story and covering up for the bits the west cannot stomach—like the rising communalism, rigging of the judiciary, and wielding the police as a tool of repression.

(Rashme Sehgal is an independent journalist.)

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.