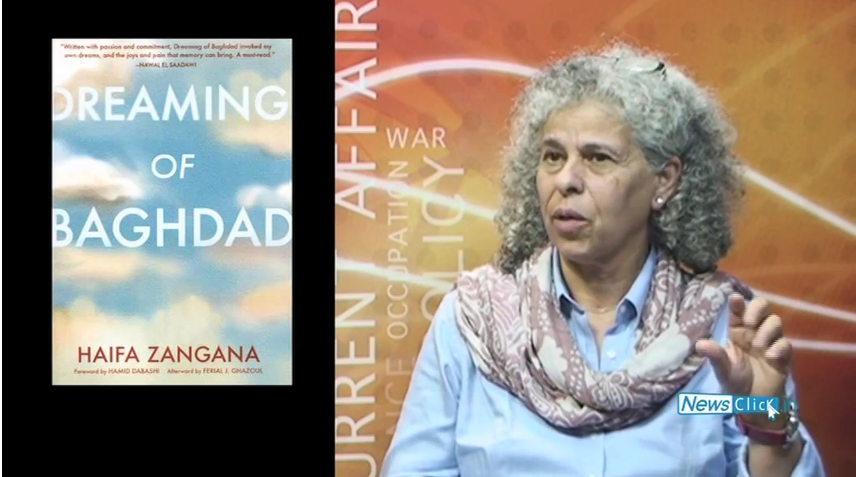

Time for All-Iraq to Rise: Haifa Zangana

Political analyst Aijaz Ahmad from Newsclick speaks to Haifa Zangana, famous Iraqi writer, artist and political activist about her works, her life and her experiences when she was imprisoned under the Saddam Hussein regime. In her first novel, Dreaming of Baghdad, Zangana recollects memories and experiences of incarceration, torture, exile and relentless political activism both inside and outside Iraq.

Aijaz Ahmad (AA): Hello and welcome. We have here today with us Haifa Zangana, eminent Iraqi writer, novelist, painter, activist. We are very privileged to have her in India for a very short visit and it is very kind of you Haifa to have agreed to come to us while you had so little time. Welcome.

Haifa Zangana (HF): Thank You.

AA: We are very glad to have you finally in India. We tried twice in the past and you were not able to come. Now, you are both a novelist and a writer. This is something that interested me in the blurbs because I thought novelists were writers. They make that distinction apparently on your books. So, let me first ask you, today also you have mentioned you have written something called an autobiographical novel. Now, what is an autobiographical novel and what is this autobiographical novel about?

HZ: Well, I had a problem while writing that book; it is called Dreaming of Baghdad. Originally, it was published under the title of Through Vast Holes of Memory. It was about the period in Iraq in the early seventies when I was arrested under the Baath regime and then was imprisoned. The first few weeks, I was under constant interrogation in a prison called Qasr al-Nahiya which is ''the Palace of the End,'' meaning if you get there, you will never..., that will be the end.

AA: Is that the name the regime gave it or was it always called that?

HZ: No, it was a palace under the monarchy. But, gradually, I mean the funny thing is the regime itself was promoting its image as brutal. It's a kind of psychological way of terrorizing people, to put them off from doing anything or taking any initiative. It contributed in a way to this image, which in the end, became instrumental in its demise of being, this fabrication, also a mix with reality about how they behave themselves. So that contributed to their name and they were proud of it. It was under the management of a very brutal person who was funny enough, or the irony of it was, after a while he was arrested by the regime and was killed. Anyway, the novel itself is about that period, which after the first initial interrogation time, I was transferred to Abu Ghraib prison, which later became famous with the American occupation and the torture in it. And from those two places, I was also taken to a smaller prison and that was for no reason whatsoever, except for humiliation; it's called Zafaraniyya, which is specifically for prostitutes. So I was kept there for a while to give me the feeling, and my family a feeling, and whoever heard about my arrest, that she is nothing but a prostitute; nothing dignified about her. This is the period I have written about, about being there, about other people who were there; why I was there...

AA: Towards the end of the book you talk about unreliability of memory.

HZ: Exactly. This is part of why I call it an autobiographical novel. I was worried that may be I haven't really presented the truth as it was. May be, I am after a while, because it was years after what happened, I sat there and written those chapters. Took a long time, one chapter after the other. So I started to question what was written. Can I claim this is exactly what happened or.. and the big shock came to me one day. I was looking through a newspaper. I got it from friends. Iraqi newspaper, and there was this small column about people missing, the dead, and there was somebody missing called Haider. That little 3 line. I was struck by the fact that I knew somebody called Haider when I was in the party. I knew how he disappeared and yet I didn't say a word about him in my book, what is supposed to be biographical or autobiographical book. So I started to think why didn't I do that. Why? Hiding this, is it a conscious decision, sub-conscious; have I contributed to his death probably; was it I was worried about the party?

AA: Contributed to his death, through your silence you mean?

HZ: Exactly. Yes. Knowing what's happened to him is being a witness and then silent someone or I didn't want to tarnish the reputation of the political movement I was part of it. So all of this. I wrote a chapter regarding the memory and how does it allure and mislead, how truthful it is, the memory and how can we rely on things, on the memory?

AA: When I started reading your work Haifa, one of the things that struck me and it has stayed with me as part of my regard for you – that you were arrested, you were tortured, you were humiliated by the Saddam regime; your family suffered, your friends suffered, your comrades suffered, and yet after the occupation when you write about this, you do not allow your subjective, personal or even collective family and comradely experience to over-shadow the fact that, as I understand you, reading your work and I am curious how you see my interpretation of it, that once the monarchy was over, there was a republican Iraq and the great fight between the Left and the Baathist regime was the fight over what this republican tradition of Iraq would mean? What kind of Iraq would we have? And part of the brutality of the Saddam regime came from the fact that – claiming it as its legacy and suppressing anybody else, all those who challenged it and something that comes through your book is that what the American invasion and occupation does is that it takes away from the Iraqis to fight out what that tradition is. There's not only a dismantling of a dictatorship but also the brutal end to a history that was internal to Iraq and super-imposing a different kind of history so that, that history becomes very difficult to recapture. That I thought was quite remarkable because a number of people, you know these are very brutal regimes, you know better than I do, whether its Iraq, or for that matter Syria, Mubarak regime and so on.. the general tendency then actually is, very often to say – good riddance, we have been liberated from it and so on, which is the argument for humanitarian intervention and so on. Your distancing from it was rather unusual I thought, lot of intellectuals must be struggling with this, both in Iraq and outside...

HZ: You are quite right, absolutely. What you mentioned about the period in the aftermath of the Iraqi revolution in 1958 and the struggle which erupted after that, the conflict between the Communist party and the nationalistic movement is there; it's not just the Baath regime but also the Arab nationalism, pro-nationalism, pan-Arab movements altogether. So we had, like the 2 tunnels almost separated, so there was no connection between the two and this immediately been, one part is the Communist party with the Soviet Union at that time was becoming the symbol for advancement of the country, the people, the peace-loving people and everybody.. the pan-Arab, and others were looked upon like chauvinistic feelings, especially in a country like Iraq where you have many ethnic backgrounds to it, so it has presented like that. The struggle between the two consumed a lot of energy of the country at that time. But the last straw was by the imposing of or coming to power by coup-d'-etat by the Baath regime and taking control of everything and almost emptying the country of millions of people gradually. So what should have been an organic struggle within the country to advance towards democracy, towards social justice, what is wanted by the people, became a weakening factor. All achievement is done after the revolution, during the first republic has interrupted. So this became the feature of what's happened later. Whenever there is advancement and development, there is interruption. Though I mean we mustn't deny the Baath regime also achieved excellent things.

AA: I was about to ask you that. One of your recent books talk more about it. There is a section where you talk about the legislation, the actual implementation of the legislation regarding women and in that you compare a speech by the secretary-general of the Communist Party, Fahal and Saddam Hussein and you sort of imply that on a number of these issues, while being deeply anti-communist, he was actually co-opting the same sort of language, same imagery, same notions as the communists. If the Soviet women were their models, they invoked Islamic women from Islamic history but the model Iraqi woman that they are trying to create

HZ: Yeah they were, it's at some point, I mean I have the feeling that it's the same coin; at least it's regarding the language, but also I mean in practical terms, the regime at that time achieved a lot regarding education, health service, the basic needs of the people; also we mustn't forget that at that time there was the oil money and there wasn't much of corruption. The money was actually used within the country. The main problem was this – you have to accept this, is almost like God. The one and only political party. Any opposition would be dealt brutally. The other thing is this kind of pushing towards being the leader in the Arab world, the jamal nasar of the Arab world after he became very strong – I am the leader and then all the budget started to go towards military. Iraq came to have 1 million army soldiers and Iraq-Iran war developed.

AA: Would you say that Iraq-Iran war was a great water-shed in the history of Saddam regime that before Iraq-Iran war, Saddam was as much a dictator as he continued to be, but until then the regime was in fact doing a lot of reformist, progressive things, while brutally suppressing. But the war disrupted even that.

HZ: It did. Economy-wise, it did. It has weakened Iraq to great extent. The development in education, health, employment and all laws came to a standstill gradually at the time of war. And also losing something like half a million Iraqi men that was devastating to the country, to the society, women, orphans; we got all these problems out of it. In fact it could have been, I hear so much from the Iraqis who were there at the time of war has ended. They reached the agreement and it's agreed upon that, the feeling of people for Saddam, they loved Saddam. They were so relieved for the first time and had the regime at that time capitalised these feelings of people of support because there was the enemy; so there were a lot of patriotic feelings and here we are, almost like you can claim victory – capitalise on those feelings and not going to another stupid invasion of Kuwait.

AA: There was time in the 70s, 80s when we used to think of Iraq as one of the most secular country – both as society and as regime, in its politics as well as in its society. Baghdad was fast becoming the cultural centre of the Arab world as Cairo had been at one point as Beirut had been at one point; of modern, progressive culture and all that, something deeply secular about that society. Comes the invasion, that society is wreaked. Shock and awe did not happen that night, it went on for years. But out of that wreckage, that politics did not survive at all. I mean it survived in small groups, resistance here and there so on...but as a significant political formation, lets say in the electoral arena and religiosity actually increased enormously as social practice in a way that you had never seen in modern Iraq. Now, this transformation, how do you actually think about it now?

HZ: I think it started before the occupation. It started during the Iraq-Iran war in 1979. We had to face Islamic republic. They started to talk openly about spreading Islam. It's not specifically about Islam in general, but they started talking about Shiatism, in that sense, because Iran is a Shia country and started talking about going openly through Iraq to the Gulf area and all that. Iraqi regime at that time felt very threatened. Saddam who sees himself as the leader of the Arab world and everything like the rest of the Arab leaders confirming this image of him specially at that time, increasingly became the symbol to face Iran's expansion. So, he believed it and he acted upon it. In order to also regain what is called our Islam, or his Islam, he started al-am-illahi, the faith campaign. It came up in the late years of Iraq-Iran war, where he forced his army officers, the people to start reciting the Quran; women started to cover their hair, there were competitions running in school, himself reciting Quran on television... So, more space was given to religion. But it's his idea of religion, in order to confront the political expansion of...

AA: The secular pan-Arab nationalism was considered not sufficient.

HZ: Not sufficient.

AA: But you had to have your own version of Islam against their version of Islam.

HZ: Exactly.

AA: And therefore, by willy-nilly you came to be seen as the Sunni answer to the Shia version.

HZ: Exactly. None of the people in the Baath party or nothing in their statement or policies previous to this had anything. On the contrary, they looked up on any Islamist movement as backward, as people who are standing against actually... by the way, many of the... I know of the Baathists, I meet them, we talk to them... they have a very firm stand against Islamism. They are a secular party.

AA: I have never met a Baathist who is Islamic.

HZ: So it's really the emergence of the whole thing. I think it's also the political parties emerging in the West. They started to capitalize about this side or that side... Exactly. And it became also a tool to get funds. We've seen it in London. Many small groups of people presenting themselves as this so they can have more funds to have centres. Centres started mushrooming in London more than inside Iraq may be... in Washington and all these organizations growing and the political party became may be part of the reasons to call for the regime change, and overthrow of Saddam is his becoming a Sunni.

AA: You actually write somewhere... in one of your books that as a matter of fact, many of the founders, perhaps majority of the founders were Shia. And as was the membership.

HZ: Yes. More than dozens of the revolutionary council of Iraq were Shia. The deputy prime minister was, the foreign minister was, we can get a long list... no one bothered about the whole thing.

AA: Except they did not identify themselves as Shia and no one else talked of it.

HZ: Exactly. I mean if you want to look into that, the lists are there, if you want to...

AA: If you were a Baathist, it did not matter. So long as you were Baathist.

HZ: Yeah.

AA: Currently in Iraq, again the violence is enormous. I mean this year the average has been about a thousand dead every month and injured... the one explanation you get in the Western media is Al Qaida, largely Sunnis killing Shias. Shias are also killing, but mainly Al Qaida, Wahabi Islam... What truth is there to this? Is it true that... I mean for example the construction in the Western media is that after... it's a recent construction actually... that after Syria, in fact, religious militias have become more powerful in Iraq, especially Sunni militias, and it is because of that now there is an increase in this kind of violence. How do you read all this?

HZ: Well, it's... if you look at the political map now, within the political parties taking part in the political process, you will see every single party got its own militia. So they all talk about democracy, they all talk about being non-sectarian, non-ethnic, 'we're all Iraqis', but they got their own militias. And their militias are highly armed. There is no law. None of them have been held in the past or in the present accountable for any crime committed. And no one seems to... can touch them. The prime minister himself been on television many times saying 'I cannot really touch this person'. He names them. 'And I cannot touch those'.

AA: And no one can touch him.

HZ: But he doesn't mention that...

AA: No one can touch him. Because he has his own militia.

HZ: Exactly. He has got his own militia. He has got his own special forces. One trained by the US, and they are attached directly to his office. So they all, all of them fighting each other whether they are trying to call themselves Sunnis, Shia, secular, non-Kurdish... all of them got their militias and they are fighting amongst themselves. I mean I can go on name so many of them where they are on the ground, armed, and they are killing each other and we know of numbers...

AA: So what about secular, progressive...

HZ: If you just allow me, I mean those militias themselves also I mean, right on top of that having the biggest embassy in the world with 5000 people sitting there in the green zone and they all will say this is the only sovereign place. Iraq is not sovereign, but this is the sovereignty that they are entitled to and it's a huge city they are sitting in. And they are the special forces, special task forces, mercenaries there are under the guise of private contractors and security contractors, the CIAs, and this is all so linked. This huge explosion... We've noticed if you sit and monitor the timing of things – when they increase, when they decrease – why did they increase last month, the last couple of months? It is also related to their relationship with Iran. So Iraq has been used as battlefield for scoring, who is what. So Iran is forcing America to look at it as a power which is actually... can handle the violence, the terrorists, Al Qaida in Iraq. They say we are the people who can control it; the other side, they claim otherwise. But whenever there is a negotiation between the two, you see a softening. So Iraq is semi-quiet. When there are problems and kind of... in the media – some shouts and screams, it increases. So this is the reality I mean. It's blurred but this is what is happening.

AA: So now there must be underneath it all, a considerable population in Iraq which continues to have more enlightened and progressive, secular temper that Iraqi people historically had. So what kind of resistance is developing among them, or are they just too terrified to resist?

HZ: No, there are... I mean we can talk about their unions. You don't hear much about it. Especially the oil unions, the south of Iraq, oil company, they've been very active for many years. Actually since the beginning of the invasion. They were on strike. Their general secretary Hassan Juma, well-known figure, I've seen him, I've met him, he is a fantastic man. He was detained. He was put on trial also. And there was a huge campaign in the country in order to release him because he hasn't committed any crime, or to drop charges, which has been successful. It's a great thing. And he is one of few unions who are combining, defending the interest of the workers plus he is talking about occupation and the unity of Iraq. So while some of the unions like electricity union, or others, they only talk about the demands of their memberships, but still that's good. I mean this adds to the general picture of resisting the unlawful situation in the country where they are now bringing workers from everywhere else in the world to work there while we have the highest levels of unemployment and we have the qualified people to work. Those are the people who after 1991 within a couple of weeks restored all electricity to Iraq and the oil fields are... everything rebuilt. The bridges... engineers, everybody. Now they don't want them. They are really not people to be trusted. Iraqis are not trusted in their country now. It became like that. The unions are doing that, some of them more than the others. But it's there. Provinces... five of the provinces in the west and the north of Iraq, they had been like in the last December, 21st of December last year until now on continues vigils and demonstrations, and they had been faced with brutal reaction from the security forces, intimidation, arrest and detention, all that is there. There is a youth movement within Baghdad and around Baghdad. So every Friday, they're going out, demanding various issues. I think what is lacking really is in this whole picture is something to unify all the demands. They are still... the demands are mostly either local or separately... different from one area to another. Time is coming for all-Iraq to rise.

AA: On that note, and with that hope, we end this conversation. But we'll welcome you back in India and we hope that you come back and visit Newsclick again. Thank you so very much.

HZ: Thank You.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.