Why Kabir isn’t Cool

Image Courtesy: Twitter

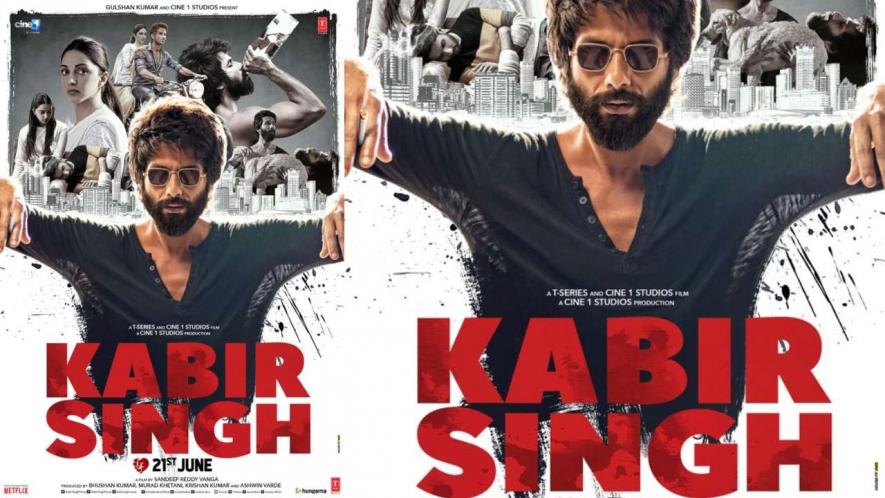

Right through Sandeep Vanga’s Kabir Singh, a statutory warning stays glued to the screen. It reminds viewers, smoking and drinking are injurious to health. What they really need is a disclaimer that unjustified anger, valorised violence, glorified misogyny and idolised self-destruction are even more damaging.

Filmmakers and actors have no moral obligation to make the silver screen fit anybody’s notions of political correctness. They operate in the realm of fiction, which is not bogged down by such concerns. Creative goals and narrative freedom would surmount those concerns anyway. What does not pass muster is the attempt to pass off a ‘romance’ replete with rage and insult as ‘cool’. The film makers often forget that hyper-masculinity is a problematic ideal even in the representational domain.

Why is Kabir so angry anyway

The principle character trait of Kabir is his anger. He claims that he is not a ‘rebel without a cause’, but we are left wondering where his uncontrollable rage comes from. No psychological explanation is given for his anger mismanagement.

The angry young man on celluloid in the 1970s was a definitive product of anti-establishment sentiment in the post-emergency period. His rage was symbolic and represented the collective angst against denial and injustice. That angry young man forcefully took law in his own hands in order to deliver justice as the state’s initiatives towards redistribution were seen to have failed in the off-screen world.

When it comes to the Bungalow-born Kabir, he is blessed with a BMW even before he starts working and lives surrounded by riches. The audience would be within its rights to wonder why he is angry and why those around him tolerate his rage?

Without these answers, Kabir’s character and his anger are simply pointless. He is hollow and empty and so are his suffering and redemption, if any. His machismo is equally superficial, pathetic in fact, and certainly uncool. What he considers his entitlement amounts to severe abuse, and we are left without a narrative rationale for any of his impositions or inner motivations.

Consent? Who cares!

At its very onset Kabir Singh establishes that its protagonist, Kabir played by Shahid Kapoor, does not give a damn about sexual consent. He keeps a woman on knife’s edge, literally, whilst she is made to strip and get physical with him. Later, viewers are told that he had “fallen in love” at first sight earlier, when he was a college student. In that time, he had publicly declared that anyone who dares gaze at “meri bandi”—my girl—will face severe consequences.

Kabir coerces “his” girl to move into the boy’s hostel with him. This is projected as the lead character’s protective instinct, while the woman is never offered a choice to decide. As Kabir’s atrocities pile on through the film, it becomes amply clear that no countervailing rules or regulations apply to him.

The very idea of consent is absent in the worldview of Kabir Singh and its makers. Kabir’s lover neither has a choice nor a voice, nothing but the ‘option’ to obey. Unsurprisingly, she is almost dialogue-less in the film, as if she has been muted. Her silence is so pervasive that it is puzzling: is she afraid to resist or does she feel compelled to accept everything without question?

Strangely, she falls in love with Kabir, a bully, brutal enforcer and egotist. Kabir is a mindless man who does not realise that he is not brave when he does not seek consent, but an abuser. To see him on screen is to feel convinced that all known understandings of love and affection are under severe threat. For instance, Kabir labels overweight women as ‘reliable teddy bears’, making an appalling and insulting spectacle of body shaming.

Slapping? That just intensifies love

From his opponents on the football field to the referee—Kabir bashes people up, takes great pride in it and finds ample support for it. His uncontrollable rage is punctuated with sketching “anatomy lessons” on the arms of his girlfriend. Or, he rides on his Enfield through town in slow motion while generally indulging his possessive streak.

When Kabir becomes a doctor, he approaches the parents of his girlfriend Preeti Sikka, played by Kiara Advani, with a marriage proposal. He drives there conspicuously in his BMW. They turn him down and that gets him all fired up again. He demands that Preeti confront her father “like a ‘man” and slaps her in public.

The film’s director has claimed in recent interviews that the slaps signify the intensity of Kabir’s love, but many would beg to differ. For, what is fictionalised also represents the mindset and intention of its creators.

There is no glory, glamour or heroism in slaps, beatings, causing hurt or leveling insults. These acts show nothing but utter disrespect. The tendency to depict abuse and justify it by drawing links with love or its “intensity” are a regressive ploy used throughout the film, to treat the body as a possession, an item to control. In this way, the film also makes the body into an innate other, which can be violated at will.

Kabir Singh takes the phrase ‘everything is fair in love’ a little too seriously. The filmmakers apparently forgot that abuse is a serious form of misconduct, whether it is directed at a lover, a child, partner or stranger. Driving a BMW and living in a McMansion (as Kabir does) does not make abuse cool.

Intoxication and relentless celebration of self-destruction

Kabir (unsuccessfully) gives his girlfriend a six-hour ultimatum to elope and then indulges in a frenzy of drug and alcohol abuse. When he comes to, he learns that Preeti is set to marry another man. Sure enough, here ensues another round of public uncontrollable rage.

The Devdas syndrome now leads Kabir to immerse himself in intoxicants. Now he is a surgeon who conducts operations under the influence. Yet, the film projects this as his genius, not a brazen and unethical violation. Overnight, he turns from possessive protagonist into a promiscuous lad on a hunt for sexual gratification. (In one scene, he pours ice into his underpants to cool off.) The nonstop despair, pain, anguish and melancholy sets Kabir up as a glorious even in suffering.

This sums up the absurd three hours long self-destructive saga of Kabir’s love, anger and poor impulse control. Glorification of self-destructive spree after a failed relationship is a cliched trope that have been done to death. The imposition without approval that Kabir indulges in is more of an imperial project and less of an intense affair.

Precious chastity and the family reunion

After he has been showered with sympathy, and thereby attains romantic martyrdom, Kabir’s melodramatic saga wins over the audience. Now all the film needs, is a happy ending—so that it can attain the status of a universal hit.

But before this, the chastity of the female character, and the moral fabric of the family, must be protected and reinstituted at any cost. The female protagonist cannot be impregnated by another male. And she is not. For her to get acceptance, she must remain ‘pure’. Hence, it becomes the film’s imperative that she remains untouched by another man. The film shows her willingly and endlessly waiting for Kabir to return so that the melodramatic climax can break out. Thereafter should follow a predictable family photo shoot. And it does.

This is the regressive framework in which the female body becomes merely a possession, protected and preserved by a man whose desire is to control it fully. Thus, the male protagonist exercises the right to ‘prosecute’ possible intruders or simply keep them outside the narrative scheme.

A sensible audience would think that such possessiveness needs a serious revision, especially in this transient and ephemeral Age of Tinder. But in Kabir’s rigid macho world, sensibilities are sacrificed in favour of enforcement and gender disparity. The dejected man has a string of sexual encounters to “cope” with his rejection while a high premium is placed on the chastity of the female lead. The moral burden of purity falls on the woman in the end.

To say that the young will emulate this shallow character after the film’s commercial success is presumptive. The extent to which characters influence life or drive behavior is still unknown. But in two linguistic zones violence and the tendency to impose sexist norms on women has gained popularity, judging by the success of Kabir Singh. This is a cause of concern and something to ponder over.

Sreedeep is a sociologist with the Shiv Nadar University

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.