Why #OK Boomer Had to Fail In India

Image Courtesy: MassLive.com

As the Coronavirus pandemic took over the world, the memetic phrase ‘Boomer-remover’ showed up on social media platforms in the Global North. The hashtag suggested on TikTok, Instagram and elsewhere suggested that the Millennials and Zoomers (or Generation Z) are outrageously gleeful to learn that people over 60—the post-War Baby Boomer generation—had a very high mortality rate if they contracted the SARS-CoV-2 virus.

This hashtag initially surfaced in late 2019 as “OK Boomer”, a meme that appeared to direct Millennial and Zoomer rage at the Baby Boomers. The triggers, it appeared, were the prospects of shrinking economic opportunities and catastrophic climate change, to which were added the perception that the Boomers were holding on to outmoded cultural norms, including ideas of relationship structures, gender, race and sexuality. The meme has also been used to express consternation at elders who do not seem to understand the importance of staying indoors and maintaining physical distance during the lockdown.

The meme found some global acceptance, for an older generation hectoring the young about “how things were back in their day” is a universal experience. Late last year Chloe Swarbrick, an MP from the New Zealand Parliament shot to fame for her perfectly-placed “OK Boomer” when a senior male parliamentarian heckled her during her speech on climate change. It was seen as a moment of Millennial vindication, a challenge to entrenched power and privilege by a marginalised section that is now asserting itself.

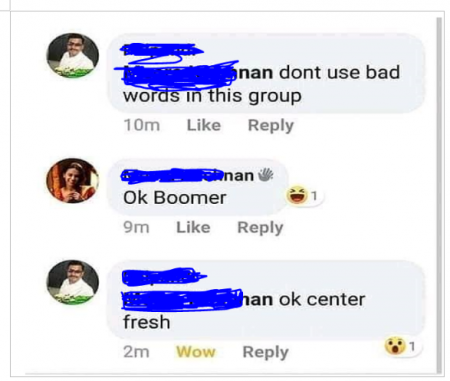

The meme caught on among some savvy young social media users in India as well and quite a few media commentators took to the term. One early instance that was circulated widely was a screen-grab of a witty to-and-fro between a young woman and an elderly man. (Pic 1, below.)

Celebrity stand-up comedian Kunal Kamra has used the catchphrase against Chetan Bhagat and, more recently, against one of his many detractors on Twitter. Journalist Ishan Tharoor, too, recently railed against his “boomer dad”, Lok Sabha MP from Trivandrum Shashi Tharoor, and his colleagues, for going to Parliament in the midst of the Corona outbreak.

During the ongoing Covid-19 lockdown, Indian Millennials and Zoomers are also being forced to reckon with extended time with parents and other relatives who can be intrusive and barge into their lives. For the economically secure and members of privileged castes, exasperated outbursts of “OK Boomer” are the order of the day. Under lockdown, many of the self-consciously progressive set (or “woke” crowd) have to deal with the discriminatory attitudes of elders in the family towards religious and sexual minorities, besides the usual caste-based slurs used by many in the older generations.

The degree to which being in close proximity to “Boomers” is felt inimical is determined by the socio-economic location of the one who feels trapped. Younger women, who had avoided being constricted by their families by going to college or university or who had salvaged their own personal liberty by working out-of-town, or generally being away at work for most part of the day, are back in the confines of homes, surrounded by restrictive family members. That is why anecdotes abound of such women being manipulated by their parents into getting married during this lockdown. The restrictions have led to a spurt in domestic violence and abuse around the world, including in India. In addition, for those dealing with mental health issues, being forced to be with family during an extended lockdown might not necessarily be the best option.

However, the plight of migrant workers, daily wage earners, the queer and other marginalised sections is markedly different from the comfortably-off Millennial or Zoomer. It would also be too hasty to transplant inter-generational conflicts from the West to the Indian context, as a closer look at the social, cultural and political outlook of India’s youth shows. A survey conducted in 2017 by the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS) in collaboration with the Konrad Adenauer Stiftung (KAS), titled “Attitudes, anxieties and aspirations of India’s youth: changing patterns”, presents some evidence of the priorities and attitudes prevailing among India’s youth.

This survey examined 6,122 respondents aged 15 to 34 in 19 states, excluding Jammu and Kashmir and the North-Eastern states except Assam and it finds that a large majority of young Indians are ill at ease with liberal values. Most favour the death penalty and support bans on films that can “hurt” religious sentiment. Most do not consider consuming beef a matter of personal choice and take a dim view of consuming alcohol and non-vegetarian food in general. More than half reported in the survey that wives should be subservient to husbands, while two in every five held the view that married woman must not go to work.

Significantly, even female respondents largely agreed to these views. CSDS’s own patriarchy index found around 54% of the respondents were patriarchal to some degree. The youth are significantly opposed in India to same-sex marriage, live-in partners and dating. Only a third of the youth fully supported inter-caste marriages; more than half oppose inter-religious weddings.

To top it, nearly half the country’s youth professed no interest in politics, while 25% said they identify with the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party—of course, this narrative has layers, including of economic anxieties, which can fuel conservatism. But the survey conducted by CSDS, perhaps unsurprisingly, also finds that support for affirmative action is higher only among the marginalised groups, to varying degrees among the OBCs, SCs and STs. Some 17% of respondents who belong to marginalised groups reported they were discriminated against on grounds of region, religion, caste, gender or economic status.

This data belies the scenario painted in India by the dominant interpretation of the “OK Boomer” meme. While an impression has been created that India’s youth is tolerant and inclusive, unlike the older generation, that does not seem to be true. Indeed, the dominant political discourse on social media chokes off India’s still considerable “offline” populace. Consider another CSDS report, from 2019. It records the finding that on social media most politically-vocal Indian youth, whether liberal or conservative, belong to privileged caste and class backgrounds and are well educated. That said, it reports that more Dalit, Adivasi and queer voices and other non-mainstream voices—such as people from the North-Eastern states—are contesting this hegemony and bringing discourses based on their lived experiences to these platforms. The report also finds that of the roughly one-third of India’s electorate with access to social media platforms, only 25% felt comfortable expressing their political opinion online.

It could be that the meme was never meant to connote a liberal-conservative divide, but only reflect the varying cultural preferences between hegemonic sections of two different generations. Or it could even just reflect the chasm that exists between their levels of familiarity with technological-cultural forms. After all, the meme was born in the roiling underbelly of 4chan, an online image-board not known for its progressive denizens. Yet the meme is an excellent avenue to understand the problems that arise when socio-political commentary is based solely on inter-generational divides, especially in contexts such as India’s, where terms such as “Boomer” hold no water as such; and caste, gender, class, sexuality, region etc. are better determinants.

Especially with regard to caste, as the past few Lok Sabha election results have shown, the fragmentation and reorientation of caste groups along existing cleavages have yielded rich dividends while the gains India’s made during its “second democratic upsurge” seem to have weakened greatly. Indeed, it is sobering that the woke Indian Millennials and Zoomers comprise a miniscule fraction even within their own privileged demographic—who are still decidedly conservative.

According to one analysis of the CSDS-Lokniti's post-poll National Election Studies data, 61% of the so-called ‘upper’ caste voters supported the BJP, as did 44% of upper-middle class and wealthy voters.

Even in the West, the Baby Boomer generation is starkly cleaved along race, gender, class and sexual identities. For instance, the successive waves of de-industrialisation, financialisation of capitalism, steady erosion of the welfare state and the recession of 2008 has wracked havoc even among White workers, but they have had a far more devastating effect on the Black working class. Indeed, the only demographics that “OK Boomer” can be aptly aimed at are the middle and upper class White males, whose fortunes were unaffected by all of these shocks. As the American political analyst Bhaskar Sunkara has said, the enemies of the downtrodden Millennials might not be the “boomers”, but “that investment banker you went to high school with”.

The folly of excessive focus on an inter-generational divide thus takes us to another more relevant direction. In recent decades, political thinkers have warned us against the lure of teleological thinking, which would have us believe that societies become more inclusive and tolerant over time with each successive generation. The Italian political thinker Gianni Vattimo has spoken of the “disorientation” caused by modernity, as previously stable social meanings are ruptured by changing socio-economic conditions (as Marx put it—“all that is solid melts into air”).

In addition, as marginalised groups struggle for their rights, the dominant universalist discourses, coded with the hegemony of privileged social classes, are contested by discourses of difference. Such developments have immense emancipatory potential, but, as the political scientist Benjamin Arditi has said, there never really is a guaranteed end point, where politics stops and utopia is achieved. Disorientation and loss of privilege can—does—lead to backlash from dominant sections against religious, ethnic and sexual minorities. In such a scenario, charismatic leaders and political parties could rise, riding on assurances to the majority of a return to the stability of an older order. This, in fact, is evident in developments over the last decade.

The Novel Coronavirus pandemic can very easily increase the potency of such leaders, as it did for Victor Orban. Very vocal woke Millennials may be over-abundant on social media but they are still a rather small sub-section of a consortium of elites held together by a “passive revolution”, as Sudipta Kaviraj had written long ago. Social media might be brimming with “woke” Millennials, but these platforms present a skewed political picture of the electorate, especially today, when the pandemic threatens to re-wire politics forever.

The author is a doctoral student at Jawaharlal Nehru University. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.