COVID-19 in Rural India- XLI: In MP’s Rohna Village, PDS Delays Challenge Food Security of Villagers

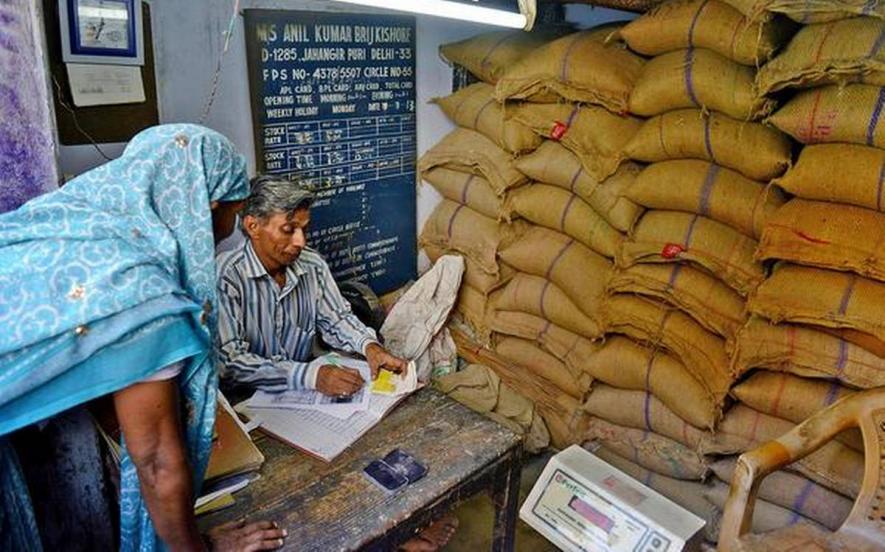

Image for representational use only.Image Courtesy : The Hindu

This is the 40th report in a series that provides glimpses into the impact of COVID-19-related policies on life in rural India. The series, commissioned by the Society for Social and Economic Research, comprises reports by various scholars who have been conducting village studies in different parts of India. The reports have been prepared on the basis of telephonic interviews with key informants in their study villages. This report discusses the challenges farmers in MP’s Rohna village have faced in selling harvested wheat and in completing preparations for the cultivation of the moong crop. The availability of agricultural and non-agricultural work in the village, food security and other challenges faced by the residents of Rohna are also discussed.

Rohna village is in Hoshangabad district in Madhya Pradesh. This is the second report on the impact of the pandemic induced lockdown on agricultural and non-agricultural activities of the COVID-19 pandemic and the government response to it.

Impact on agricultural activities

Ninety-five per cent of the cultivable land in Rohna is used to grow wheat during the rabi season. The wheat harvest was completed at the beginning of April. Almost all the farmers in Rohna sell their wheat to the state government and the co-operative society in the village acts as the procurement centre for this. The procurement process was delayed this year, and farmers thus had to store the grain either in their houses or in barns temporarily coveredwith plastic sheets to protect it from the rain. The procurement process finally began on April 15, but it is proceeding at a lower pace than last year. For instance, by May 9, 2019, 61,000 quintals had been procured but only 31,000 quintals had been procured by the same date in 2020. One reason for this is that tasks like the weighing of grain and the loading of the sacks onto trucks are taking place more slowly. These tasks are usually carried out by migrant labourers from Bihar who have not been able to travel to the village this year. In their stead, the procurement centre has employed young men from within the village whose inexperience leads them to work more slowly.

Also, most farmers have had to wait between 18 and 20 days after the sale of their wheat for the payment due to be credited into their accounts. One farmer who owns 2.5 acres of land sold his wheat on April 18, four days after the start of the procurement window. He received money in his account on May 9. Such delays impact farmers in crucial ways, by limiting their ability to purchase items needed for household consumption as well as agricultural inputs necessary for their next crops. Some small farmers have even sold a part of their grain to the local grocery shop at a much lower rate (Rs 1,500 to 1,600 per quintal rather than the minimum support price of Rs 1,925) in order to meet their needs.

Usually there is a period of 15-20 days between the harvesting of wheat and the sowing of moong. During this period, farmers typically harvest dry straw, an important by-product of wheat that is used as fodder by village households that rear livestock. Households would normally be able to stock up on enough dry fodder at this time to last the entire year. But the delay in the harvesting of wheat in 2020 also resulted in the straw harvesting period being reduced to eight or ten days. There was also a shortage of straw-reapers in the village. As a result, many households could not harvest enough straw and will have to buy it at higher prices later in the year.

Moong is an important cash crop cultivated by around 50% of the farmers in Rohna, all of whom have their own source of irrigation. This year, reports that water would be released from the dam on the Tawa river, making canal irrigation possible, had encouraged many other farmers to consider cultivating moong. After some uncertainty, water from the dam was released on April 10. Several farmers complained that the supply was irregular but said they have refrained from raising the issue with government officials ostensibly because they would be preoccupied with the pandemic. Some farmers have abandoned their plans to sow moong due to the delayed harvesting of wheat. One farmer who owns 3.5 acres land reported that he had bought moong seeds but decided against sowing them as he did not think there would be enough time (around 60 days) for the crop to grow before the monsoon. Other farmers sowed their crops late but plan to use a chemical that can dry the plant overnight to mitigate this during harvesting.

The moong crop requires three to four rounds of pesticide application. These pesticides are not available on credit as they are comparatively more expensive. Many farmers, most of whom have been unable to sell their wheat until now, are finding it extremely difficult to procure the necessary pesticides. Some have resorted to taking short-term loans from their acquaintances to make up the shortfall, but many are finding it impossible to get loans, as even the more prosperous households are unwilling to lend money in these uncertain times. Some farmers have made arrangements among themselves to share fertilisers and pesticides for now.

Many farmers in the village also anticipate a rise in the cost of harvesting moong. Several households in the village own combine-harvesters, so the farmers are not anticipating a shortage in the availability of these machines but they are expecting an increase in the prices charged by the owners. For instance, one owner of a harvester plans to charge Rs 1,600 per acre this year—he charged Rs 1,200 per acre last year in the nearby districts where he hires out his harvester. And given the exceptional circumstances, farmers are in no position to bargain.

Repercussions on non-agricultural workers

Most men and a few women from the landless households of the village commute to Hoshangabad city every day to work as construction labourers or in the city’s shops. They earn around Rs 250 to 300 per day. These workers have been rendered jobless for the last 50 days and most of them have not been able to find alternative sources of income in the village. As noted above, some young men have been employed by the co-operative society, but women and older men have not found employment.

Below, there is a summary of the experiences of three individuals to convey the impact of the pandemic and the extended lockdown on workers in different industries and circumstances.

Twenty-year-old Rajesh has been working at wholesale cloth supplier’s shop in Hoshangabad for the last 18 months. He is the sole breadwinner in his family and earns Rs 4,000 per month. The shop has been closed since March 22 and he received his last salary on March 17. His colleagues requested the shop owner to give them some money or a part of their salary for the month of April but the shopkeeper refused. Rajesh did not take up the temporary employment (two months’ worth) available at the co-operative society because he was uncertain about the duration of the lockdown and would have lost his job at the shop if he did not report for work once it reopened. He had deposited Rs 5,000 at one of the local grocery shops when the lockdown began. By April 30, his family had already bought groceries worth Rs 3,000 from this shop. Rajesh has no other savings except the remaining Rs 2,000 deposited at the grocery shop. If the cloth shop remains closed, he is worried that he will have to borrow money. He says that his family will not be able to obtain more than Rs 1,500 to 2,000 on credit as most of his acquaintances are also going through a tough time financially.

Fifty-five-year-old Rahim works as a tailor in a shop owned by his nephew in Hoshangabad city. The shop has been shut since March 22 and his family of three has been dependent on the rations they received under the public distribution system (PDS) in mid-March, which are now almost entirely used up. Rahim has not had the money to buy essential medicines in the last month. His household does not have a Jan Dhan account, and so they did not receive the cash transfer of Rs 500 announced by the government. Rahim’s wife is employed as a maid by the self-help group that cooks midday meals for the local school. As she is not a permanent employee, she has not been paid her salary since March.

Karuna, a 33-year-old woman, lives with her seven-year-old daughter, her parents and two brothers. Her brothers are daily wage labourers in the construction sector and have had no work since the lockdown began. Karuna works as a tailor from her home and earns around Rs 6,000 per month. Typically, the months of April and May are crucial for her tailoring business as weddings usually take place at this time. However, she has not had any new tailoring jobs owing to the lockdown and people’s unwillingness to spend money on clothes at this time. Her parents collected one quintal of wheat from gleaning the fields and the family has used their savings to purchase other essential food items over the last month. According to Karuna, there is not much agricultural employment available as many farmers are using family labour in order to avoid paying for hired labour.

Some villagers work in two spinning mills in the nearby district. These workers were sent away from the gates of the factory on March 23 and have not yet been asked to come back to work. The factory obtained permission to resume operations after being shut for eight days. It has since operated at 33% capacity with workers who live in the factory quarters within the city. More than half of the labourers in these factories are those who commute from nearby areas. They have not been called back to work yet. A supervisor at one of the factories said that the management had decided to pay their labourers’ salaries for the month of April but there might be a week’s delay in the disbursement. He was of the opinion that the factory would not return to operating at full capacity until public transportation services normalize. He also said the management might not want to invest more money in production during this uncertain time.

Various small shops in the village, including eateries, barber shops, tailoring shops and general provisions stores run by the residents have been shut since the imposition of the lockdown, and the owners are desperate to resume work.

Even though, there has been a massive demand for employment in the village, work under MNREGA has not started. This could have provided the much needed succour to landless households.

Impact on food security and household finances

Most families have almost exhausted the rations they received under the PDS in mid-March and are awaiting the next installment. There is as yet no news about when this will take place. Both the anganwadis in the village have been shut since the announcement of the lockdown. Anganwadi workers have been distributing only sattu (roasted gram flour) to pregnant women every Tuesday as there are no funds to procure other food items. The midday meal scheme has come to a halt ever since the schools shut.

Economically vulnerable households in the village often purchase essential commodities on credit and at slightly higher prices from the local grocery shops. However, grocery shops in the village are no longer giving food items on credit. This has intensified the financial crunch for many daily wage workers’ households. Simultaneously, the prices of most commodities have increased as the lockdown has continued to be extended. For instance, the price of cooking oil has gone up from Rs 95 to Rs 110 per litre; the price of groundnuts from Rs 100 per kg to Rs 126 per kg; the price of sugar from Rs 38 per kg to around Rs 45 per kg. The prices of milk and vegetables have largely remained the same, but many households reported a reduction in the consumption of these commodities due to a lack of funds.

An additional expense for most families is the money spent on tobacco and bidis, and the prices of these commodities have increased sharply. A bundle of bidis used to cost Rs 22 but is now being sold for Rs 50. A pouch of tobacco used to cost Rs 40 and now costs Rs 60 or more. The consumption of alcohol has continued during the lockdown. Villagers reported that people have been purchasing locally brewed alcohol (extracted from the flowers of the tropical mahua tree) from a neighbouring village.

Many small farmers and manual labourers had purchased mobile phones, television sets and a few other household durables on monthly instalment plans. The necessity of making these payments on time to avoid penalties is adding to the financial burden on households that have suffered a loss or reduction in income during the lockdown.

To conclude, the delay in the procurement of wheat, disruptions to key agricultural operations, and the lack of means to purchase agricultural inputs are some of the most important problems being faced by farmers in Rohna. The impact of COVID-19-related restrictions on landless labourers has been immense: many have been rendered jobless and have had to use up their meagre savings to purchase essential commodities.

[This report is based on a survey of 17 respondents conducted between May 1 and May 13, 2020.]

The author is a research scholar at the Centre for the Study of Regional Development in Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.