Do the Math: India’s Covid-19 Relief Package for the Poor

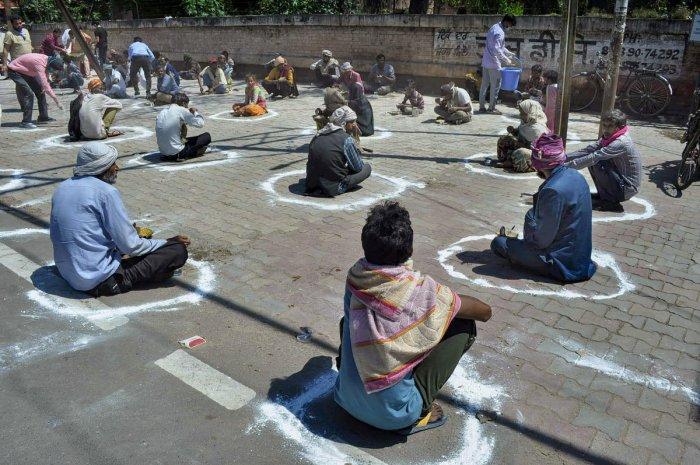

Representational image. | Image Courtesy: Deccan Herald

Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s 8 PM address on 24 March, announcing a 21-day lockdown, has unsettled a large portion of India’s close to 5 crore migrants workers. After the announcement, large groups of people hit the roads on foot to reach their home-towns and villages. However, these poor folk faced police lathis as they were seen as violators of the lockdown rules.

The panic that triggered people to take to the roads could be attributed to the lack of an assurance, which, in this context, is the delay in the announcement of a relief package. The Pradhan Mantri Garib Kalyan Yojana [Prime Minister’s Scheme for Welfare of the Poor], was announced on 26 March, with the Finance Minister claiming that the package was for “the poor who needed immediate help like migrant workers and urban and rural poor”.

The package announced by the government, pegged at Rs 1.7 lakh crore, includes an itinerary of measures ranging from cash transfers to farmers and women, insurance schemes for paramedics, doctors and supporting medical staff, loans for self-help groups and a fillip to existing schemes like Ujjawala (gas cylinders to households) and Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Scheme (MGNREGS).

We analyse the package in the context of the FM’s claims and argue in favour of an urgent need for increased state participation, broad-basing of the relief measures and saturating the system with enough funds to help vulnerable sections of society and fight the pandemic confronting the nation.

Beneficiaries, benefits and exclusions:

The first of the announcements was that under PM Kisan Samman Nidhi Yojana, an instalment of Rs 2,000 will be paid to 8.69 crore farmers by the first week of April. While the cash transfer does not involve any new allocation of funds, the number only accounts for 70% of the beneficiaries of the scheme, leaving behind close to 3.81 crore eligible beneficiaries. Government data suggests that the scheme has enlisted 12.50 crore eligible beneficiaries for the year 2018-19. Moreover, the scheme already did not include landless agricultural labourers who accounted for over 10% of the population (14.43 crore) in 2011.

Secondly, it was announced that the per-day wage of the beneficiaries of the MGNREGS—a guaranteed-employment scheme—would be raised from Rs 182 to Rs 202, seeking to benefit 5 crore people. Notably, official data indicates that the number of workers under MGNREGS has been on a rise and has gone up from 7.22 crore individuals (4.81 crore households) in 2015-16 to 7.81 crore individuals (5.44 crore households) in 2019-20.

In the event of restriction of agricultural activity, logic informs that the burden on MGNREGS would increase. However, data suggests that 65% of the bottom 40% of the population has been unable to access the benefits of this scheme. Furthermore, the means to gain from MGNREGS stands diametrically opposite to the current need to stay indoors. If carried out, the scheme portends to expose the workers to the danger of contracting the Covid-19 disease.

Thirdly, the package set forth a provision of an extra five kilograms of rice/wheat per person per month, in addition to the existing 5 kilograms, along with one-kilogram pulse per household for a period of three months. Claiming to benefit 80 crore individuals, this measure relies on the existing Targeted Public Distribution System or TPDS framework, which uses Below Poverty Line (BPL) cards to account for the beneficiaries.

Data suggests that the Targeted Public Distribution System (TPDS) suffers from nearly 61% exclusion error and 25% inclusion error of beneficiaries (December 2013). That is, it misclassifies 61% of the poor as non-poor and 25% of the non-poor as poor. A deeper look reveals that 40% of the poorest 40% are excluded from the TPDS. In this context, the relief measures stand to pass on the structural defects, which we cannot afford at the time of a humanitarian crisis, that too in a caste-based hierarchical society.

Alternatively, the government should aim for a universal distribution system, mirroring the policy followed in Tamil Nadu, so that the ongoing tragedy is tackled better, as data shows that the universal distribution systems have the minimum leakages as compared to TPDS.

Benefits, relevance, and sufficiency:

The government announced a hike in the value of the collateral-free loans given under the Deen Dayal Upadhyaya National Rural Livelihood Mission from Rs 10 lakh to 20 lakh. The announcement appears ideal and even a tad ambitious. However, in the wake of reduced economic activity and rising Non-Performing Assets (NPAs), questions regarding the relevance of such measures are pertinent.

Another measure of the package provided for an “ex gratia” payment of Rs 500 per month for the next three months to women holding Jan-Dhan accounts. According to the government, this will benefit 20 crore women. However, data suggests that 11.48 crore Jan Dhan accounts are non-functional, that is, either they are zero-balance accounts or they are inactive.

As per the report on women’s financial inclusion by MicroSave Consulting, 23% of women have lack of access to financial services and around 42% have inactive bank accounts in the past year. Instead, in trying times like today, money orders through the postal department could be considered as an option to enable last-mile delivery of benefits. Also, such an approach could be undertaken with the transfer of Rs 1000 to 3 crore widows and senior citizens in two installments over the next three months.

Rejigging accounts, fresh infusion, and broad-basing for last-mile reach:

A recent paper prescribes a 49-day lockdown in India, to help flatten the Covid-19 impact curve in India (Singh and Adhikari, 2020). In this context, it would be safe to argue that a six-month relief package to the households at the bottom 50% of the Indian population in terms of income, both rural and urban, of the Indian population would be a fitting response to help their sustenance. The All-India Rural Financial Inclusion Survey 2016-17 by NABARD estimates that the average monthly consumption expenditure of rural Indian households, agricultural and non-agricultural, is Rs 6,646.

If this were to be taken as a standard measure for the sum of money that would be transferred to each household per month for six months, then the government would need a sum of over 6 lakh crore rupees. A corpus of this size, which the state governments too can draw from, would facilitate the cash transfer of roughly Rs 6,000 per month, along with a universal distribution of groceries under the PDS and provision of free on-demand walk-in meals for people across the country.

In other words, instead of adopting the existing framework that seeks to target the delivery of public goods, the government needs to universalise the provision of public goods. Increased spending owing to exclusion error would ensue i.e., some people who do not need such support would still get access to subsidised goods, but such an outcome is unavoidable owing to the gravity of our current predicament.

The needs of the healthcare sector need to be addressed on an urgent basis for which funds need to be raised separately.

Currently, the Union government has said that it will utilise the funds available under the District Mineral Fund for testing activities, medical screening, and providing health attention needed to fight the Novel Coronavirus pandemic. As per the latest data, 70% of district mineral fund is lying idle and only 30% has been spent for drinking water supply, sanitation, women and child care, welfare of aged and disabled people in the mining districts. However, instead of diversion of money from such poorly-utilised yet important funds, it would help if the unused money were utilised for their dedicated purpose, which would in turn enable vulnerable groups face the current crisis.

That said, in terms of rejigging, the funds set aside for infrastructure projects could be diverted towards the relief package. Also, the dip in the already low crude oil prices is a money saver, and experts peg the savings on India’s imports at close to Rs 2 lakh crores if the current prices hold for a year. Moreover, the Union government has advised state governments to address people’s concerns on a range of issues, which in the current GST framework—with states constrained in levying taxes and the transfer of funds to them reduced—is a difficult task.

If the situation prolongs, the states would find it increasingly difficult to handle their needs without support from the Union government.

Drawing from Jaffrelot et al. we note that the dire circumstances confronting us today engender apprehension towards ideas like ‘minimum government—maximum governance’, proclivity for private charities as against government welfare policies, and fixing of responsibility of societal welfare on the society itself through self-regulation. While the charities are doing their part at the moment, they are by no means a substitute for government intervention and the latter needs to assume a far greater responsibility in comparison to the former. A case in point is the need to facilitate continued supply of goods across the country to avoid the apparent supply crunch in the lockdown period.

On a broad note, to begin with, fresh funds can be raised by deferring the adherence to fiscal deficit cap imposed under the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act. The fiscal deficit is at around 3.8% of GDP, which is 0.8% more than the cap imposed by the Act. While the actual total fiscal deficit including that of states and public organisations stands at around 9%, a 2% increase (around Rs 4-5 lakh crore) over six months, in phases, seems to be a pertinent move that would enable the government to alleviate the struggle of the poor of the country.

Vignesh Karthik KR is a PhD student at the King’s India Institute, King’s College London. Saumya Gupta is a business analyst specialising in strategy and has a masters in social sciences from the University of Chicago.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.