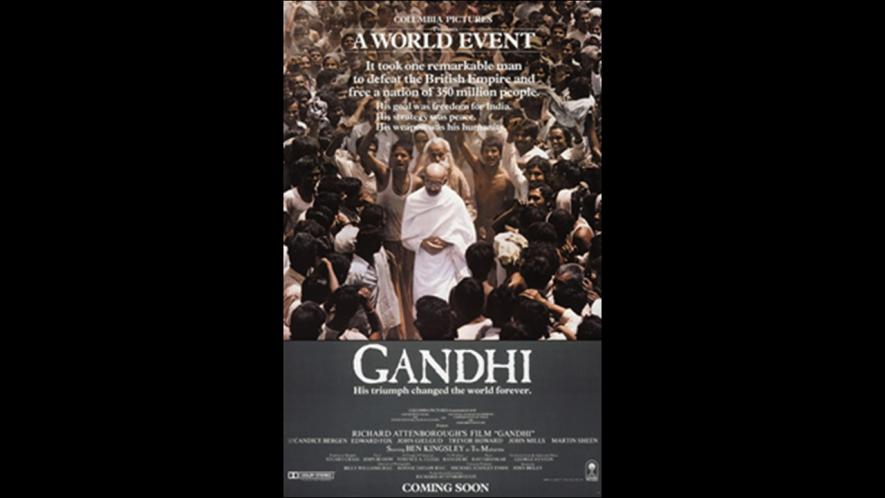

How Attenborough’s Gandhi Anticipated Lockdown Image

Image Courtesy: Wikipedia

For close to 40 years British film-maker David Attenborough’s iconic movie, Gandhi, has shaped the popular imagination of India’s struggle for freedom. It is therefore ironic that nobody noticed when one of the most tragic scenes from the film recently became a reality in India.

Halfway through Attenborough’s film is a heart-rending scene of an infant wailing next to her mother’s bloodied corpse. The mother and child feature briefly but prominently in the horrific five-minute sequence on the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar. That is where on 13 April 1919 the British Brigadier-General Reginald Dyer had ordered unprovoked firing on a large gathering.

A hundred years after the Amritsar massacre and forty years after the film Gandhi, videos of infants next to their dead mothers, crying and disoriented, have been circulating in India. One of these is of a woman daily-wage worker from Bihar and the other of at least two such women from Madhya Pradesh. Unlike the film, these women did not fall to bullets fired on the command of cruel generals. They perished during their arduous journeys home from the cities they worked in after the government suddenly locked down the country to slow the spread of Covid-19.

In Attenborough’s movie, the Amritsar massacre depicts a cruel imperialist power attacking a hapless gathering. The wailing child in that episode symbolises the fate of India under men like Dyer, who represent a cold-blooded British empire. By contrast, today’s government is an elected one, which did not intend for these women to die. This makes it doubly incongruous—for two fundamentally different regimes separated by a century have produced exactly the same images of infants mourning their mothers.

Nature of the Indian State

The tragedy that befell the mother and child in the film existed only to bolster Attenborough’s plot. He projects the firing at Jallianwala Bagh as the zenith of colonial abuse. The desolate child was a device to evoke pathos and enrage viewers against British rule. This would justify to his audience why the plot immediately turns to Indians demanding freedom at any cost. Judging from the popularity of the film, the devise struck a chord.

Today’s context is incomparable with 1919, but the images of crying children next to deceased mothers still tells us about the nature of the Indian state. For one, it demonstrates the state’s indifference to the poor. From the moment the lockdown was announced, it was criticised for lacking in planning or foresight. For the other, it is the fault of the state that the hardships of migrant workers were not accounted for when the wheels of the economy were halted with four hours’ notice.

The dead women were among the millions who were forced to return home, tired and hungry, the one from Bihar in an overheated train and the others, from Madhya Pradesh, in a hired truck that overturned killing six. The government could not have anticipated their death. Yet this failure was largely because it prioritised the concerns of the middle class and the wealthy, leaving the poor with no sources of income.

Empathy and History

Another departure from the plot of the film Gandhi is that most of those who saw on TV or social media the travails of the migrant workers did not think that the government has lost its moral justification to wield power. It is ironic that India’s movie-goers could empathise with Gandhi the film, but not with a scene from it that leapt into real life.

The Amritsar tragedy, as depicted in the movie Gandhi, has left an indelible imprint on the Indian psyche. Yet it is not an accurate snapshot of history. The historian Kim A Wagner writes in his deeply-researched book, Jallianwala Bagh: An Empire of Fear and the Making of the Amritsar Massacre, “The photographs taken of the Jallianwala Bagh shortly after the massacre show only an empty space. It has thus been left largely for Attenborough’s movie to fill in the canvas of the popular imagination and provide the visual repertoire through which today we approach the events of 13 April 1919.”

Wagner writes: “Since the release of Gandhi, however, a spate of popular Indian movies, including Shaheed Udham Singh (2000), The Legend of Bhagat Singh (2002) and Rang de Basanti (2006), have again drawn from, if not outright copied, these key scenes [of Jallianwala Bagh] from Attenborough.” So the scene in which the “ground is littered with dead bodies, and a small girl is crying next to the bloodied corpse of her mother” was a creative reconstruction by Attenborough and his script writers: there is no record of a mother and her child exactly as they were shown in the film.

This belies the popular perception in India that the film Gandhi faithfully reproduces history down to the last detail. Such a reproduction would naturally be impossible for any film production, but in an interview published in the New York Times on 28 November 1982, a week before Gandhi’s theatrical release in New Delhi and London, Attenborough explained how he chose what to feature or not in his movie. “I work as an actor works, to involve an audience by engaging their emotions, to interest them in the story you are putting before them,” he said. He also acknowledged to the newspaper that the selection and exclusion of events and characters would risk his film’s claims to objectivity, but he needed “to winnow ruthlessly”, keeping in mind the entertainment requirements of a feature film.

So the sobbing child next to her mother is not a sliver of history captured on celluloid but a dramatised version of what might have taken place on 13 April, 101 years ago. As Wagner writes, “...the violence unleashed on the unarmed men, women and children at Amritsar is entirely embodied by [actor] Edward Fox’s Dyer: a man seemingly incapable of emotions, who appears as nothing so much as an automaton.”

It follows then that the death of the women migrants over the last couple of months does not repeat history but an amplified cinematic version of it. The film which had Indians convinced that colonialism was fated to fall after an atrocity like Jallianwala Bagh could not relate to the real life version of it. It is another matter that in history the Amritsar massacre did not lead to a sudden end for England’s control over India, but a slow build-up of resentment and popular movements. Freedom was still almost three decades away.

Shattered Reality

The Indian state, obviously, was not trying to turn a pre-existing image of a disaster into reality during the lockdown. Rather, the reality of the Indian state’s neglect and callousness caught up with it during this pandemic. Perhaps what happened is akin to something the Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek says in his essay “Passions of the Real, Passions of Semblance” on the 9/11 attacks and the American public’s reactions on seeing the twin towers collapse, “It is not that reality entered our image: the image entered and shattered our reality...”

There is no doubt that a state, through exercising its powers, can make its visions come true—like conducting election campaigns using holograms, implementing divisive projects like the National Register of Citizens or running a bullet train and so on. But the state had not envisioned tormenting migrant workers when it closed India down on 25 March. Instead, driven by concerns of the middle class, which was paranoid that public health facilities would collapse if the poor contracted Covid-19, it planned a lockdown that insulated the better-off from its own failings.

That is why daily wagers and informal workers, though they are 90% of the workforce, were “forgotten”. In other words, the death of migrant workers was a tragic outcome of state policy, and another reminder that India does not care about its poor. It is likely that most people distinguish the acts of a state based on their intention and so even when the poor were mowed down on railway tracks or died of hunger or in road accidents, they did not question the state. It is also possible that they might take months if not years to craft a change, as had happened after the massacre in Amritsar.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.