Is India Ready for Post-Covid Employment Crisis?

The Covid-19 pandemic has triggered the largest global economic recession since the Great Depression almost a century ago. Gita Gopinath at the IMF has pegged the global output loss at around 9 trillion dollars for 2020-21. Fears of hunger and starvation deaths are not misplaced. This unanticipated catastrophe has already claimed over one lakh lives across the world so far, and counting.

However, the lockdown during the pandemic has brought economic activities to an abrupt halt, taking a toll on millions of livelihoods. From salaried employees, freelance workers and private school teachers to daily wage workers, migrant labour, street vendors, and home-based workers, the threat of losing their means of livelihood looms large; more so for the latter economically vulnerable groups.

Unfortunately, what remains is uncertainty. In a country like India where around 90% of the labour force is employed in the informal sector, more than lives are at stake.

Mounting unemployment

As per NSSO data for 2017-18, the rate of unemployment had shot up to a worrisome 6.1%, a 45-year high. The role of the twin shocks of demonetisation and GST in arresting growth and devastating employment cannot be downplayed. While the economy was already in terrible shape and yet to recover from these shocks, the Covid-19 pandemic has thrown a final blow and will certainly leave the economy into tatters.

The rate of growth for the last quarter of FY 2019-20 is likely to be negative. What is most worrying is the colossal loss of jobs as a result of the lockdown beginning 24 March. The rate of unemployment has surged with each passing week of the lockdown, as illustrated below.

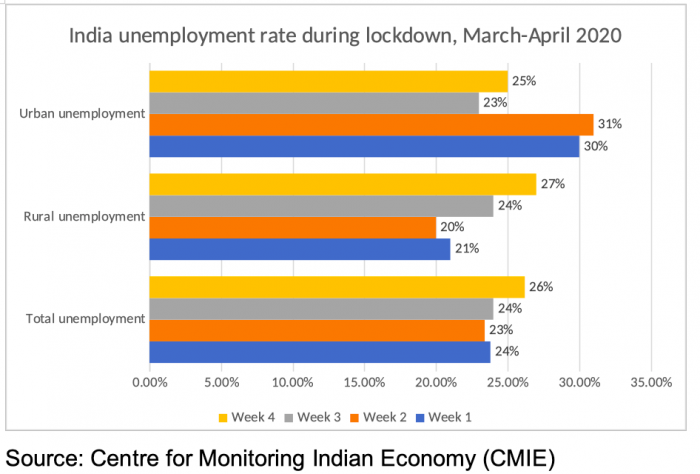

According to CMIE estimates, the unemployment rate was 6.7% for the week ending 15 March 2020, just before the lockdown commenced. It shot up to a staggering 23.8% in the very first week of the lockdown. It declined slightly in the second week, only to scale up to 24% in the third week.

The upward trend continued during the fourth week, towering at an appalling 26.2% during the fourth week of lockdown ending 19 April. Simply put, one in every four members of the labour force is now out of work. It is obvious that a vast majority of these are situated in the informal sector, often in precarious employment with neither security of job nor social insurance.

Employment was badly hit in the urban areas where the rate of unemployment soared up to 30-31% in the first two weeks. By the end of fourth week, it touched around 25%. Rural unemployment has been increasing from 20% in the second week to 27% in the fortnight that followed.

Against the usual trends, rural unemployment has been exceeding urban unemployment. One of the main reasons could be the inability of farmers to reap the Rabi harvest and perform other agricultural activities. Notwithstanding the partial relaxation of the lockdown and gradual resumption of agricultural activities in the non-containment areas after 20 April, it is difficult to predict how long it would take for the rural agrarian economy to recover.

Informal sector

The ILO estimates that about 400 million informal sector workers in India will be further impoverished as a result of the lockdown. Migrant daily wage workers who constitute a significant majority of the informal labour force are also at the bottom of the pyramid in terms of their working and living conditions. A survey conducted by Jan Sahas Social Development Society revealed that more than 80% of migrant workers have food stocks that would last less than a month.

Furthermore, about 60% of the migrant workers were found to be unaware of any Covid-linked relief schemes. With the lockdown extended, savings exhausted, debts piling up and no sources of income, the same plight has befallen street vendors, domestic workers, home-based workers and the like. As uncertainty looms, no relief seems to be in sight for any of them.

The persistence of informality is essential for the survival of capitalism. Once production resumes in the post-lockdown era, it is certain that the newly hired labour will be exploited to make up for the profits forgone during the lockdown. With millions of jobs lost, the reserve army of labour shall expand, forcing them to accept work even at low wages, work overtime for no or little extra pay, as well as increase the casualisation of the workforce.

Layoffs and pay cuts

During the 2008 global recession, approximately six lakh Indians lost their jobs in a span of four months. More recently, around the same number of engineers were laid off in the IT sector in 2017.

However, it must be noted that these crises worst hit the financial and IT sectors, with relatively mild shocks felt by the others. Unfortunately, the ongoing situation is far worse.

The formal sector shall also not remain untouched by this employment crisis. Although some organisations have struggled to stay afloat via work-from-home regimes, the losses in revenue have been enormous across industries. The shutdown has already resulted in withdrawals of job offers to new recruits, retrenchment of existing staff, and pay cuts of 25% or more during work from home. Several industries in the services sector, particularly tourism, aviation and hospitality and accommodation have had to completely shut operations. The upshot is that employees of the airline GoAir and some engineers of SpiceJet have been sent on leave without pay until 3 May.

To cite another example, The Indian Express newspaper has initiated a salary cut for its employees citing a decline in revenue from advertisements alongside a plunge in sales during the lockdown. On the other hand, with newspapers no longer being delivered to homes, offices, libraries, and other readers, distributors and vendors are rendered temporarily (and indefinitely) jobless. The latter, who might not enjoy social insurance or legal protection, have to wait for the lockdown to be lifted to be able to earn any income again.

Such workers in the informal sector with meagre incomes and little-to-no savings are much more vulnerable to job losses, destruction of sources of livelihood, notwithstanding the difficulty in finding gainful employment once normalcy is restored.

Everything said and done, there is a need for a special economic task force to bring the economy back on track and deal with the employment crisis that has already begun to impact millions in India alone. The 1.7 lakh crore relief package announced in late March is being considered inadequate. The need of the hour is to adopt greater and immediate relief measures for the most vulnerable and worst hit by the pandemic. The task at hand is not only to deal with the disaster but also prepare for what is to follow; to secure not only lives but also their means of livelihood.

Aishwarya Bhuta is a student at JNU, Delhi and Dhanashree Gurudu is a research associate at a leading non-profit in Mumbai. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.