While India Slept

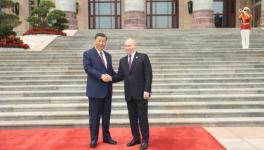

File Photo.

It is elementary wisdom that in modern wars conventional military balance alone is not decisive. Had it been so, the Axis Powers would not have lost the Second World War, the Soviets the Cold War, or the Americans their Vietnam War. What ultimately matters is the intrinsic strength of a nation’s polity and its resolve to take on any adversary with rock-solid determination, behind which lie an integrated society built upon a concrete and egalitarian economic base and correct international connections. As such, the final script of the India-China showdown has not yet been written. But if the trailers are to be believed, the omens for India are bad.

But first things first. What has really happened on the border? Has China actually intruded into areas that India considers its own, or at least into the so-called “no-man’s land”? If so, by how much? If China alone has violated the LAC (Line of Actual Control), what is this “mutual disengagement” we keep hearing about? Why is India not clearly demanding “Chinese withdrawal” from areas it has intruded into? Why did the Indian government send confusing signals in the beginning, from which it has yet to wriggle itself free? Have not the Chinese taken full advantage of this Indian “faux pas” to bolster their domestic support base, which is in any case in their pocket, being the totalitarian state that they are.

In this hurly-burly, the one reality that stands out is that Indians were caught napping. To put it bluntly, they were lulled into complacency by the Chinese lullaby; Narendra Modi by Xi Jinping, much as Pandit Nehru by Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai nearly sixty years ago. The core question is: why is India always taken for a ride by China; why is it found defending or recovering land allegedly lost to the Chinese? Why this perpetual reaction, why no pro-action? The answer is simple: While India sleeps, China is active, even super active.

It is possible that the ongoing diplomatic parleys will make India convince China to restore the status quo ante as of April (how each country would interpret that is a million dollar question), but will that alter the reality that China is head and shoulders above India in real terms? After all, barring comical claims of being the “wisdom-giver to the world” (vishwaguru), India has done little meaningful to narrow the ever-widening gap.

International relations is a cut-throat field. Power speaks through overall strength, not mere good intentions. Most of us in India, or probably anywhere else, are obsessed with comparing nations through the parameters of GDP or military balance. They are important indicators, but they often bypass in the calculations those that should figure centre-stage: the masses.

Being a student of South Asian politics for decades, and having interacted with my counterparts across the region, I have convinced myself that howsoever much we may try to warn of growing Chinese influence in the region, to our neighbours it cuts little ice. For them, both India and China are giants. When you sleep with elephants you sleep in perpetual fear, never sure to which way the mammoths will turn. For historical and ethnic reasons, these countries have more to worry from New Delhi than from Beijing. The latter is too far away and, in any case, India serves as a good buffer. Let India absorb the shock first. Pakistan’s advantage is geo-strategic in any case.

More importantly, in constant search for resources and support to pursue their development agendas, the smaller South Asian nations love to make India and China compete over who can be a better friend to them. As a potential donor, China is much better positioned than India.

A decade ago, with the help of my economist friend Prof. Taranath Bhat, I tried to make a comparative India-China chart to understand where we relatively stood in development terms. To make our chart look comprehensive we deviated from the beaten track of comparing GDP-PPP or military expenditures and arsenals. Instead, we looked for their respective commitments to their masses in terms of daily needs. Here are some interesting revelations based on data culled from World Bank and UNDP fact-sheets, the China Customs Statistics 2011, and the Economic Survey of India for the years 2010, 2011 and 2012.

The Chinese population stood at 1.35 billion, India’s at 1.21 billion a decade ago. China’s GDP in PPP terms was $9.87 trillion vis-à-vis India’s $3.91 trillion; annual per capita GDP in PPP terms was $7,599 versus $3,425; and the defence budget stood at $106.4 billion $40.5 billion, respectively. Now, consider these development indicators in terms of their reflection in people’s welfare. In China, 29.8% of the population survived on less than $2 a day; the corresponding share in India was 54%. Adult literacy in China stood at 96%, in India at 76%; and the Human Development Index (HDI) ranked China at 101 and India at 134.

China produced 16,200 doctorates in science and engineering every year, India barely 7,300; China had 5,20,000 vocational and training institutes, India just 12,260. China’s child mortality rate (under 5 years per 1,000) in 2010 was 18 compared to India’s 63. China’s per capita electricity consumption was 2631 kWh, while India’s was 597 kWh. China’s annual steel production of 683.3 million tonnes dwarfed India’s figure of 72.2; in cement production, the ratio was 1,800 million tonnes to 220 million tonnes. In the ten years since we collected these figures, these trends have diverged, not converged.

In the context of the COVID-19 pandemic and the difficulties faced by the health services of both countries, it is instructive to remember that comparative expenditure on health was far higher in China. In 2010, the per capita expenditure on health in China was $265 while in India it was barely $122. According to WHO statistics, the corresponding figures for 2017 were 441 versus $69 (yes, India reduced its spending on health!). If India wants to deal with China on an equal footing, each of these metrics matters.

One last point. The easiest thing in the world is to become a state-defined nationalist. The moment one becomes such a nationalist, his critical thinking goes into slumber and he basks in the glory of the greatness of his nation. His reverie is disturbed only when he realises that the world beyond his walls has not lain idle but has instead steadily encroached into his home. But by then it is already too late. His house has been burgled in and his pride punctured.

To my mind, the most frustrating field of social science research is International Relations (IR). The reasons are numerous, but for our purposes here two prominent ones will suffice: one, the inherent compulsion for IR scholars to toe the official line; and two, its fundamental weakness to be normative, howsoever remotely. This is exactly what has happened to India’s China policy. Our state-sponsored nationalism has lulled us to such an extent that we have lowered our guards to an unimaginable level.

There is absolutely no harm if Narendra Modi warmly hugs Xi Jinping or decides to swing merrily with him on the Sabarmati lawns. But India’s External Affairs Minister, S Jaishankar, should certainly have known better than to take any of these activities at face value. Indeed, his childhood education ought to have proved sufficient. The son of India’s doyen of international strategic studies, K Subrahmanyam, Jaishankar must surely have learned early and learned well that in international politics what matters is an adversary’s power, not his intentions. Furthermore, one would assume that in a democracy a foreign minister has the ear of his prime minister.

Postscript: In 1938, a year before the beginning of the Second World War in Europe, Winston Churchill wrote While England Slept. His point was simple. England had not prepared itself sufficiently to deal with Nazi Germany’s economic and military build-up. The book was an indictment of Neville Chamberlain’s so-called “policy of appeasement”. Among its readers was a young John F. Kennedy, future American president. In 1940, Kennedy graduated from Harvard College, having written a thesis titled “Appeasement at Munich,” which was largely inspired by Churchill’s book.

That same year, he sought to publish it as a book, and chose a title that would pay homage to the book that inspired him: Why England Slept. Publication was likely facilitated because of the good offices of his rich and influential father, Joseph P. Kennedy, then the American ambassador in London. The older Kennedy even approached the famous British political scientist Harold Laski to write a foreword for the book. But Laski declined, dismissing the book as the product of “an immature mind”. Laski was convinced that it would not have found a publisher had it not been written “by the son of a very rich man”.

The younger Kennedy had the last laugh, however. Why England Slept sold 80,000 copies in America and England and earned him $40,000 in royalties. He donated part of the money for the reconstruction of the war-ravaged British city of Plymouth. With the remainder he bought himself a Buick Convertible.

The author is senior fellow, Institute of Social Sciences, New Delhi. He is former ICSSR National Fellow and professor of South Asian Studies at JNU. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.