It Still Takes a Loud Voice to Make the Deaf Hear

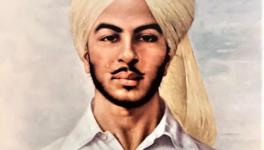

On 8 April 1929, two young Indians, aandolan-jeevis, exploded two harmless bombs in the hall of Central Assembly (present-day Parliament) and shouted the slogans Down with Imperialism, Long Live Revolution, and Workers of the World, Unite! After smoke filled the hall, Bhagat Singh and Batukeshwar Dutt showered leaflets which began with the immortal declaration: “It takes a loud voice to make the deaf hear.”

Indians who eulogise Bhagat Singh and other Indian revolutionaries know the first line of the pink pamphlet thrown in the Assembly. However, they have a scant idea about what the British were deaf to. Was it about granting freedom to India? Or something else? The leaflets thrown by Bhagat Singh and BK Dutt on behalf of the Hindustan Socialist Republican Association were against two draconian bills, the Trade Disputes Bill and the Public Safety Bill which the Viceroy, using his special powers, wanted to pass despite opposition from the nationalists.

These bills sought to curtail the growing power and assertion of the Indian working class. They aimed to gag the independent press and arrest leaders of the working class.

The Bombay textile workers went on strike eight times between 1919 and 1940. Each time, their movement lasted for more than one month. In 1928-29, it lasted for more than one year. Apart from Bombay [now Mumbai], such strikes took place in Ahmedabad (1918, 1923), Sholapur (1920, 1928), Calcutta [now Kolkata] (1920-21, 1929), Jamshedpur (1920, 1922, 1928), Madras [now Chennai] (1918, 1921) and in the Railways (1928). After the historic Bombay strike of 1928, the British government unleashed brutal oppression of the trade unions and working-class activists.

The beginning of the Great Depression in 1929 worsened the situation. In Bombay, the factory owners started throwing workers out of their jobs, began to ask for more work from fewer labourers, decreased wages, and increased workloads. Similar policies by TISCO led to a strike by 26,000 workers at Jamshedpur, and in Calcutta, 2,72,000 jute mill workers struck work in 1929. Here the communist-led Workers and Peasants Party was the most important working-class organisation. In Bombay as well, the Girni Kamgar Union was communist-led.

The rising communist influence in Indian politics greatly alerted the colonial state. To curb the trade union movement, it came up with the legislations mentioned above. The Public Safety Bill allowed the arrest of any communist activist who was coming to India from abroad such as Philip Spratt, Hutchinson and Bradley, to help Indian workers in the name of what we now call national security. The Trades Disputes Bill virtually banned strikes by factory workers and criminalised trade unions.

A significant crackdown on the communists came in March 1929 when thirty-one working-class leaders were arrested from all over India and tried under the fake charge of conspiring against the King-Emperor. This came to be known as the Meerut Conspiracy Case. Two very close comrades of Bhagat Singh—Sohan Singh Josh and Kedar Nath Sehgal—were also put on trial in this case. Even this repression could not curb the spirit of the workers and the entire year of 1929 witnessed strikes in cotton mills, jute mills, and the Railways.

Despite protests by Indians in and outside the Assembly, the British adamantly decided to use special powers to thrust the two black laws on the people. The British had turned a deaf ear to the demands of the Indian opposition, and it was against this deafness that those two aandolan jeevis decided to make a loud voice.

Fast forward from 1929, and we see the present government behave in many respects like the oppressive alien British government. For over four months, farmers from Punjab, Haryana, western Uttar Pradesh, and other parts of the country have sat at the gates of the national capital, demanding the repeal of three new farm laws that were passed amidst protest and chaos in Parliament and without consultation with farmer unions.

The farmers braved Delhi’s harsh winter and are now preparing to face heat waves, while a government that claims to rule on behalf of the common people has only become more adamant.

That the present government is behaving like an extension of a colonial state is also evident from how it has dealt with dissent in general in the last seven years. It has attacked labour laws and trade unions through four labour code bills in the name of reform and economic development, and it has used colonial-era sedition laws to arrest and silence those who raise questions.

After suppressing the critical independent media through a coercive state apparatus and new legislations, it has promoted communalism (akin to the British policy of divide and rule) to prevent united mass action. The present government is apparently taking a cue from the same textbook which guided the alien government.

The British used to delegitimise Indian freedom fighters and revolutionaries by calling them misinformed, trouble creators, gullible, funded by Russians (Bolsheviks) and branding them terrorists, etc. The present government and its supporters have employed the same paradigm to deal with dissent. The social media machinery of the ruling party and corporate media keeps branding farmers as Khalistani terrorists, anti-nationals, funded by foreign powers, and misguided, etc. to create a narrative of legitimate police crackdown upon protesters.

Young revolutionaries such as Bhagat Singh and Ashfaqullah Khan, commenting on the bourgeois nature of the mainstream Indian freedom struggle once said that Congress is fighting to replace white rulers with brown rulers. This warning and observation seems to have become real, as the present government is displaying the same arrogance towards the toiling Indian masses, once shown by the British government. In these times of struggle and despair, the historic legacy of Bhagat Singh and BK Dutt, and the protests of Indian farmers and workers, are a source of inspiration.

Prabal Saran Agarwal and Harshvardhan are Ph.D. scholars at JNU. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.