Kota Infant Deaths and Rajasthan’s Dwindling Health Budgets

The tragic death of more than 100 children in JK Lon hospital in Kota, Rajasthan, has brought the status of health facilities in the state of Rajasthan back in focus. We need to understand why health services in the state are extremely weak. Medical equipment in government hospitals did not suddenly deplete. What we see in JK Lon and other hospitals is a result of years of neglect and low budget allocations for health and family welfare in the state. It also reflects misplaced priorities within the different health programmes.

Consider the health budget of Rajasthan over the last few years: the lack of infrastructure, shortage of medical equipment and malfunctioning equipment are linked to the low budget for these expenditures over several years.

In 2015-16, the 14th Finance Commission’s recommendation to raise state’s share in the central pool of revenues from 32% to 42% was implemented. Thereafter, the share in central taxes in the budgets of all state governments, including Rajasthan, increased. However, the Central government slashed other grants that were being provided to state governments as also reduced the budget for Centrally-sponsored schemes including the National Health Mission and the Integrated Child Development Scheme (ICDS), the two major national schemes for health and nutrition respectively. Additionally, the Centre also raised the percentage contribution from state governments in these Centrally-sponsored schemes. As a result, the budget of the National Health Mission got slashed.

Health Budget in Rajasthan: Stagnant and Under-utilised.

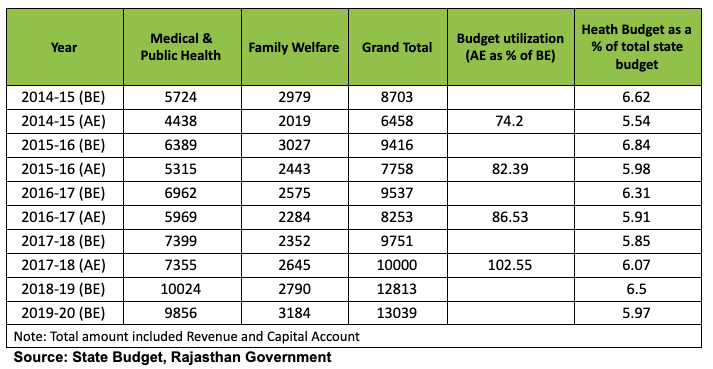

Consider now the various components of the Rajasthan government’s budget to see how priorities within the health budget changed. The table below provides data on the total budget for health and family welfare in the state.

Table 1: Budget for Health and Family Welfare in Rajasthan (rupees crore)

The table above shows that the health budget in the state increased from Rs 8,703 crore in 2014-15 Budget Estimate (BE) to Rs 13,038 crore in 2019-20 BE, an ‘impressive’ increase of 49% over the period. However, the size of the total state budget increased by 65% in this period. So, obviously, the health and family welfare budget was not a high priority in these years.

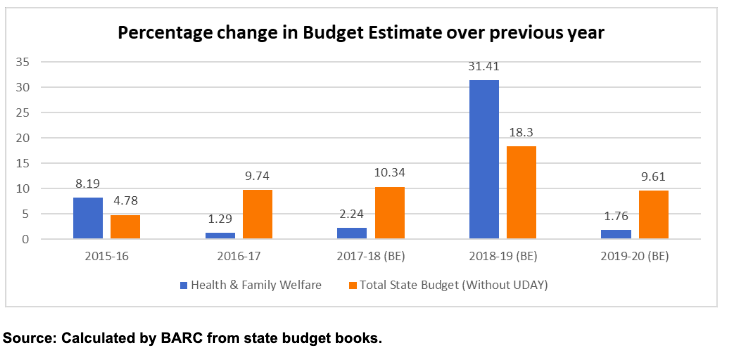

The chart below shows year-wise increases in the health budget and overall state budget in Rajasthan since 2014-15.

The chart shows how the budget for health and family welfare increased marginally, specially in 2016-17, 2017-18 and again in 2019-20, though the size of the state budget has been increasing on a fairly good pace in all these years. The above trends clearly show that health and family welfare has been a neglected area by the previous government, which was in power until 2018. The new government has also not done much to improve the health budget.

Even the allocated budget has not been fully utilised in most years. The underutilisation of budgeted funds was as high as 26% in 2014-15 which declined to 17.5% in 2016-17 and 13.5% in 2017-18. The budget was fully utilised only in 2018-19 (102%) and we do not have data on actual expenditure after that.

Low Expenditure on Infrastructure and Health Equipment

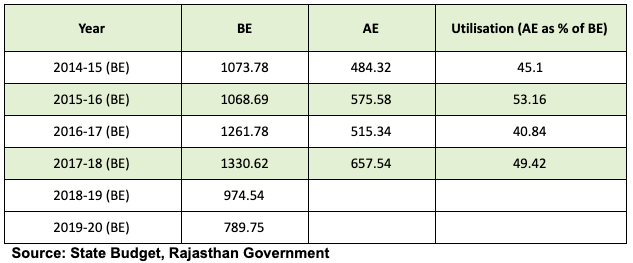

Within the health budget, notice the low, stagnant and declining expenditure on the capital account. The capital expenditure is used largely to improve infrastructure and purchase/maintain medical equipment.

Local newspapers report that in seven children’s hospitals of Rajasthan, 44 ventilators, 1,430 warmers, 730 infusion pumps and 900 nebulisers are not working. They also say that 450 extra beds are needed in these hospitals.

Procuring new infrastructure and purchasing medical equipment requires a capital budget. The table below shows the figures for the capital account budget for health in Rajasthan.

Table 2: Capital Expenditure on Medical and Public Health in Rajasthan (rupees crore)

The capital expenditure budget for medical and public health has not only declined from Rs 1,073 crore in 2014-15BE to Rs 789 crore in 2019-20 (BE), only about half of it has been utilised over the years. Even in 2017-18, when the utilisation rate of the health budget was more than 100%, the capital account budget was under-utilised by 50%. This, obviously, would impact the infrastructure, medical equipment and their maintenance in state hospitals.

Policy of Privatisation and Focus on Insurance

The state health budget has also been affected by the undue focus of the previous government on privatisation of health services. The result of this is that the Primary Health Centres (PHCs) and Community Health Centres (CHCs) in both rural and urban areas have been handed over to private organisations. Further, an insurance scheme called Bhamashah Scheme was promoted at the cost of other government schemes to provide primary health care to all.

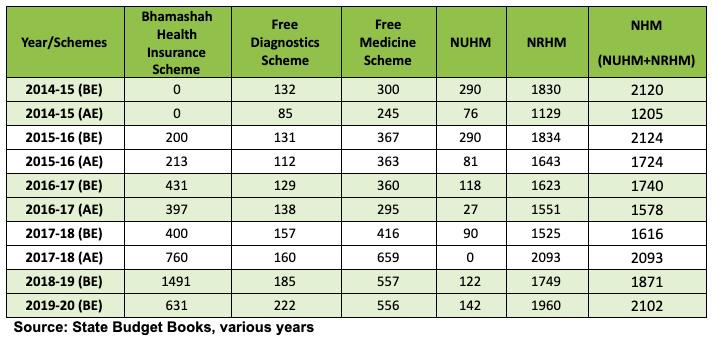

The table below shows the budget allocated to select health schemes in Rajasthan.

Table 3: Budget for major health schemes in Rajasthan (rupees crore)

Bhamashah Scheme: A Priority

The Bhamashah Health Insurance Scheme was started in 2015 by the previous Vasundhara Raje-led BJP state government as a flagship scheme. The allocations to this scheme increased manifold from Rs 200 crore in 2015-16 (BE) to Rs 1,491 crore in 2018-19, only to be slashed in 2019-20, when the newly-elected state government decided to merge it with the central government’s health insurance scheme, Ayushman Bharat.

But the budget for primary healthcare schemes, to provide essential services such as free medicine and diagnostic services, which had been started by the previous Congress government before 2013, stagnated in first three years of Raje’s coming to power. The budget for these schemes started increasing slowly only in 2017-18 after mounting pressure from civil society organisations and health rights groups.

This sequence of events highlights how primary healthcare was neglected to favour the insurance scheme, which mostly promotes privatisation. The government has tried to encourage people to seek healthcare in private hospitals by providing insurance money through insurance companies. In fact, only investments into improvement of government-run primary healthcare centres will benefit the poor.

Weakening of the National Health Mission

The budget for the Centrally-sponsored National Health Mission (NHM) had been declining since 2015-16, when the Central government decided to slash the budgets for all centrally-sponsored schemes. The NHM budget in the state only started increasing slowly after 2017-18 but it has still not touched the pre-14th Finance Commission levels.

The NHM budget in the current year is Rs 2,101 crore, still lower than the Rs 2,120 crore in 2014-15. Also, the level of under-utilisation of the budget of NHM and other schemes is excessively high. The above table suggests high underutilisation in NHM from 2014-15 to 2016-17 and the expenditure increasing only after 2016-17.

Lack of Doctors and Health Personnel

There are various reasons for health budgets not being fully utilised. For instance, delays in transfers of funds within government, delays in getting approvals from authorities, bureaucratic reluctance in taking decisions, and so on. But an important problem affecting the health system is that sanctioned posts in the medical department remain vacant. Vacancy of doctors in the state is as high as 24% for senior specialists, 37% for junior specialists, 32% for senior medical officers, 22% for medical officers and 20% for dentists, according to the annual report of the department of medical, health and family welfare.

Posts of nurses, pharmacists and technical staff are also vacant in very large numbers: 20% for nurses, 45% for pharmacists, 43% for lab technicians, 74% for lab assistants, 37% to 45% for radiographers, and 71% for assistant radiographers. Such vacancies are also not a recent development. This is a persistent problem that has only gotten worse over decades of not being addressed by successive governments.

This neglect of prolonged neglect of healthcare and low health budgets is the reason why the poor suffer, especially women and children, who are dependent on public healthcare. The death of poor children in the JK Lon Hospital in Kota is due to apathy and must be addressed urgently.

The National Health Policy 2017 aims to raise the health budget (state and central government combined) from 1.15% to 2.5% of GDP by 2020—this very year. However, the central government’s allocation to the health budget has stagnated at 0.3% of GDP and at around 2% of the total union budget since 2014-15.

State governments are also expected to raise their health budgets to 8% of their total budget according to the National Health Policy. But in Rajasthan it hovers at 6% or lower. Obviously, there has been no substantial increase in public investment in the health sector in the country as percentage of GDP after this policy was adopted. The common people who depend on the government healthcare system are facing the consequences.

The author is director of Jaipur-based. BARC (http://www.barctrust.org/index.jsp) The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.