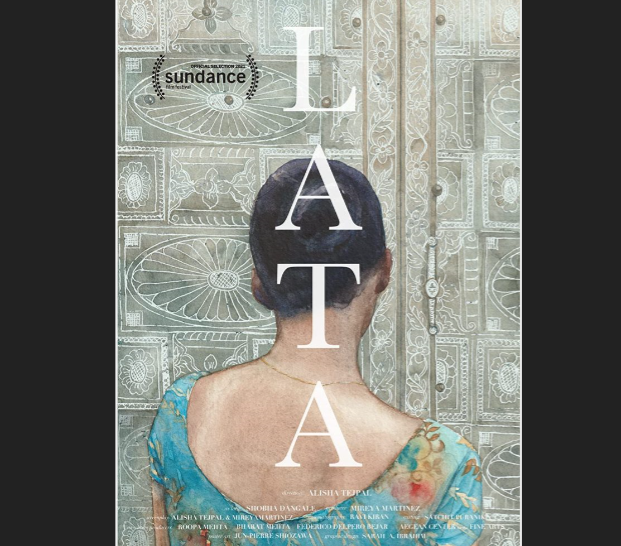

“Lata is at the Intersection of My Aesthetic Questions and My Political Ones”

As 2021 draws to an end, Alisha Tejpal’s short film, Lata, has had an exceptional run in the international film festival circuit. Starting with the Sundance Film Festival, it went on to play at the International Film Festival of Rotterdam, the Indian Film Festival of Los Angeles and the San Sebastian Film Festival. It came home to India recently at the Dharamshala International Film Festival and will be competing at this year’s International Documentary and Short Film Festival of Kerala that is being held in Thiruvananthapuram from December 9-14.

Tejpal’s 21-minute film shines light on a vital member of our homes — a crucial part of our lives who usually goes either unnoticed and unacknowledged or is not celebrated as much as needed — the house help. It’s a slice of daily life of the live-in help Lata (played by a real-life domestic worker Shobha Dangale) in a rich South Mumbai home. The film is as much about her daily drudgery as her personal dreams and ambitions and the little moments of joys she seizes for herself.

Early in the film, there is a long bathroom cleaning sequence that highlights how things can be at other people’s mercy for the domestic workers, how life could come to uneasy holds and delays because of the apathy of the privileged. It stares back hard at us again as Lata is forced to wait for the elevator while other ladies get on it first. Little moments add up to say a lot — the neighbour shuts the door on her as though she doesn’t exist. Yet, despite the callousness that surrounds her, there is a self-awareness in Lata — she has a voter’s card and is learning English, the language of upward mobility. There is the urge to seize the joys like the revelry and dancing at the Ganapati festival. And a bonding with the lady of the house who tells her that she is looking beautiful when she dresses up for the festivities.

Lata talks effortlessly about intensely problematic class and gender issues without ever getting in-your-face or pedantic. Tejpal plays with the defined limits these divides impose and the possibilities to transcend them. She is distanced yet intimate in her gaze. A film that “straddles the spaces in between documentary and fiction”, Lata is a social, personal as well as a political document. Its politics resides as much in the people it frames, as it does in the architecture of the house in which it is set — how it distances, divides and invisibalises.

The Los Angeles based filmmaker talks about her themes, concerns and filmmaking approach in a detailed interview with film critic Namrata Joshi. Excerpts:

Still from Lata

Namrata Joshi (NJ): You have followed a lovely observational approach in the film, tracking Lata from a distance which is objective yet insightful. It enables you to place a wider lens on her life, making the film both encompassing and intimate. Was that an approach you always had in mind or did it evolve as you went about writing and shooting the film?

Alisha Tejpal (AT): An observational approach combined with long shots was one of the few things I was clear about since I began the writing process. Partially out of my own interests in formalism but also to constantly remind the audience that we, and I as a maker, are looking in as outsiders. We are only privy to as much as is accessible to us, Lata is entitled to her privacy.

From its inception Lata straddled the spaces in between documentary and fiction. The film is more of a re-enacted document. We crafted a script out of collected moments, constantly aware of the liminal space in-between us as recorders of reality and the unfolding of reality itself. This observational process also deeply informed the structure of the film. The composition is meticulously controlled, infusing the film with a self-awareness of its own creation, of the deeply constructed nature of “realism”.

From its inception Lata straddled the spaces in between documentary and fiction.

NJ: How did the idea for the film come about and what was the journey into making the film like?

AT: I have been chewing on the idea for this film for a long time now. I think its seeds were first sown in a seminar on [Belgian avant garde and feminist filmmaker] Chantal Ackerman that I took at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts) in my second year. I was mesmerised by Jean Dielman, a film that examines the life of a single mother over three days the first time I saw it and I think I knew then that I wanted to work with a slow, patient camera as Lata unfolds.

At first all I had were graphs and rules I laid out for the process of making this film but no real story or characters. The process of writing this film was as much a process of questioning my own ethics around making a work that puts power, class and caste dynamics at its centre as it was a creative process to find my cinematic voice and piece together this new language.

While Lata was in many ways a formal exercise, it was also a deeply personal one. It is a subject matter that surrounds us and that is as much a perpetuated construct that we live with as it is a systemic problem. It’s at the intersection of my aesthetic questions and my political ones.

Still from Lata

NJ: You have got a certain slice of Bombay spot on. Has it been your reality, your home, people you know? How personal is the film? Where all did you shoot it in Bombay?

AT: I filmed in my own home, so this has, to an extent been my reality. From the start I knew I wanted to film within my childhood apartment, it was the only way I could ensure that the process of making this film was itself in constant critique of the system it was replicating on screen, that it also implicated me, my cast and my class. The film is personal in this sense but also fictional in that it has been scripted and constructed to stand on its own.

We filmed in and around South Mumbai, primarily in my own apartment building and with a cast that consisted of my own family members and the domestic labourers that maintain my apartment building.

NJ: What has your larger journey into filmmaking been like?

AT: I am born and raised in Mumbai. I only moved to the US for higher education, first for an undergraduate degree in Transitional Justice in Post Conflict Societies and then many years later to pursue an MFA in filmmaking at CalArts. After my undergrad, through a series of serendipitous events, I ended up studying large format photography and painting at the Aegean Center for the Fine Arts in Paros, Greece. In many ways I owe a lot of my transition to cinema to my time spent at this incredible place. I studied painting — quite specifically focused on classical and renaissance painting techniques — under Jane Pack and I remember knowing quite early on that I didn’t have what it took to be a painter. I loved every minute of it but the canvas and the brush were not my medium. But images and the frame beyond the canvas continued to mesmerise me. I think it was at this point, after four years of fighting with the paint that I decided perhaps it was time to try my hand at the moving image. I do think though that my interests in both politics/human rights and painting have come to deeply inform my work as a filmmaker now. They found a happy union in the moving image.

The frame is only a device that gestures towards a fragment of reality, time does the story telling.

NJ: As a filmmaker you exercise a delicate, quiet yet willful and sure hand on the material. Never laying things out or being literal/expository. Is that the style and approach you like to adopt in general or was it suited for this particular film?

AT: I think the unfolding of time on screen is itself an expose. It is the world beyond the frame that begins to expand and infiltrate the frame. The frame is only a device that gestures towards a fragment of reality, time does the story telling.

And while I think that certain aesthetic elements will make their way into my future work, they are always in service of my continual fascination with the world beyond the frame — for which there are a myriad cinematic approach that I am excited to continue exploring.

NJ: The limited space Lata inhabits herself within the home and how she moves within the large home with a sense of authority while at work… In the context of the class divides, is it indicative of her defined space yet the possible porousness of the structure? Or is it a reinstatement of the divides which have always been there and are likely to stay?

AT: We have built a system that works so seamlessly that I can go through my entire day without seeing an entire set of people. It was the architecture of the postcolonial home in India that fascinated me. In many ways I wanted this film to function as an architectural blueprint of the ways in which space divides and restricts access. In fact, one of the first elements of the sound script was a rhythmic opening and closing of doors which later also informed the edit.

Spaces and the bodies within those spaces all carry evident traces of their political histories and in that sense the space itself is a character endowed with its own gestures that becomes palpable over time as bodies (with their own political histories) interact with it. The urban space in India still holds visible traces of a colonial past and lifestyle and while writing this film it was important to us that the house and its expanse be felt palpably.

In many ways I wanted this film to function as an architectural blueprint of the ways in which space divides and restricts access.

Lata’s relationship with this space also brings to question themes around public vs private space: who has access to privacy when and how. Urban landscapes are designed to uphold an illusion of privacy, one that exists only if we render those that maintain and work these spaces invisible — the drivers’ quarters below the foyer of the building, the helps’ quarters in the corner of the house with an easy access back door that leads straight to the stairwell — these are all deeply thought-out architectural elements.

NJ: You introduce Lata to us with her back to the camera and stay on it for a while. She is a presence who is significant yet somehow faceless, who floats around, busy with never-ending chores. How important was the focus on her daily grind?

AT: Her daily grind is as much an observation of time as it is of labour. The privilege of time and the privilege to define one’s relationship to time as work or leisure. Also, I was particularly interested in the sounds of labour that surround spaces like these, the ways in which sounds of labour have become so entrenched in our auditory landscapes that we almost don’t hear them anymore, but they exist all around us.

Still from Lata

NJ: In your portrayal of the class dynamics, things are neither hopeful and positive nor entirely dire. Tell us a bit more about this inbetween-ness please.

AT: I wouldn’t quite call it an in-between-ness. I do not think it is necessary for me to show a character that is in dire need of help or for there to be a dramatic event for us to examine a deeply unfair system. I also do not think it is my place to give Lata a voice (she already has one!) or to free her on celluloid. This film is a meditation on the ways in which we systemically render a population invisible — from architecture to language, utensils to waiting areas. The repetitive micro-violences that ensure that the people who work for us feel indebted to us and dare not ask for more!

NJ: Lastly something about your actors. Are they all real people playing themselves on screen? What about Shobha Dangale who is fantastic as Lata? How did you come to cast her?

AT: Most of the cast of this film are first time actors and include a combination of members of my own family and workers/domestic labourers that maintain the apartment building I live in. But none of them are playing themselves on screen, they are playing a variant of themselves, an alternative version. The only professional actors in the film are Kirthi Kadam, who plays the Election Commission’s officer, and Veena Nair as Anu, who we see lying on the sofa while the family watches TV.

This film is a meditation on the ways in which we systemically render a population invisible — from architecture to language, utensils to waiting areas.

Shobha Dangale, who has worked as a domestic labourer herself, was an absolute treasure of a find and we owe so much of that meeting to Satchit Puranik and his casting team. From the start I knew that I wanted to work with non-professional actors and that Lata, the protagonist, had to be cast from within the domestic labour community.

The process of casting was a long and daunting one. It was not easy to convince young women who worked as maids to come to auditions. But Satchit and his team did such an incredible job despite all of the barriers that came with the task.

Shobha was incredible. From the very first audition she was present but for various reasons we almost ended up working with someone else except that she eloped two weeks before the filming and that’s how we arrived at Shobha. During the filming it became more than apparent that she was the best thing that could have happened to the film.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.