An Unequal Society’s Struggle to Change

Trinidadian-British writer VS Naipaul may have got his historical thrust wrong, but may have been on point with other articulations about India. India remains, as the titles of two of his ‘India Trilogy’ books say, A Wounded Civilization and an Area of Darkness.

India’s is a complex society. Its overlapping features do not lend themselves to easy social analysis. German political philosopher Freidrech Hegel had represented India as a “stagnant Orient” due to its caste system. What India is witnessing today with the rise of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and its parent, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), is this insidious civilisational aspect. Caste—not just as a sociological variable but as a deeply psychological criterion—is key to understand why this combine and its abrasive politics is on the rise.

The ladder-like structure of the caste system has created segmented and mutually hostile social groups. Each rung perceives the society and politics around it from its own vantage point. Social location thus determines how individuals view what they see. Over time, this system has produced a wounded psyche: Almost all social groups are caught up in the same process of psychological injury and historical bereavement.

In such situations, there occurs a pervasive sense of loss of the self, either in history or by history. While those placed on the lower rungs of the caste echelon lose their sense of self in history, the elite castes have lost it due to historical changes that have come about. Therefore, self-confidence is still an unresolved issue in India. This is not only true for the “lower” castes, but even for the upper echelons. The result is that India’s social elites do not really represent a self-confident identity.

Such a pervasive sense of being wounded and betrayed and of loss of self, when it cuts across castes, fuels a widespread negation of being. This universal sense of loss is what the Right has been able to mobilise. They understand this deep “civilisational” lack over which most modern processes are built and worked into reality. In India, reality is far too injurious, and too difficult to come to terms with.

While the elite-castes feel a sense of betrayal, the non-elite castes feel a sense of humiliation. It is this process that the Right understands all too well, and it they take it beyond the binary divisions of modern-constitutional sensibilities. Change—or social transformation—is neither linear nor gradual nor cumulative. It is painful, transitive and tendentious.

In such a social formation, dreams, imagination and fantasy are always inextricably mixed with reality and quotidian everyday life. We live because we fantasise about both our past and our future. As Jean Jacques Merleau-Ponty, the French existentialist said, our dreams are nothing but a particular mode of human existence in general.

Fantasy and the imaginary are not unreal but “an oblique approach to presence and being”. In a society that suffers from a perennial diffidence, inferiority and uncertainty about social status and recognition that cuts across caste, religion and region, fantasy and imagination play a significant role in re-constituting a sense of self and a semblance of confidence.

Right-wing politics emerges from this deep reality. It, in fact, belongs to this reality and does not merely make use of it. It represents the epitome of such civilisational wounds. It understands that social groups continue to suffer from a pervasive sense of loss of self. There is no easy way to move from here towards self-reflexive subjectivity or transparent dialogue.

What the Right is doing is to wedge open and stoke this suffering. It is allowing it to express itself in its most crude and unreflexive form. It is promising redemption in being retributive. It is promising liberation from inner repression. It is asking us to find meaning in others’ suffering and dignity in our own suffering. Every social group, from the brahmins to the dalits, are finding this proposition attractive. This is because it provides them with an opportunity to externalise the sense of humiliation that was being silently suffered.

This form of politics is generalising the pervasive sense of injury, thereby exposing society to an underlying existential reality. This is a reality that secular-constitutionalism attempted to bury, without first finding a resolution—a kind of burial before death.

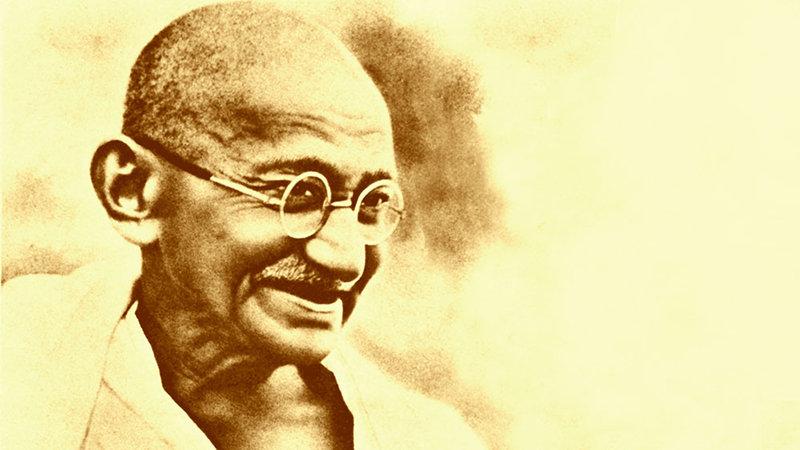

Redemption through retribution has its own path dependency. That is, once triggered, it cannot easily be retrieved. This is why Gandhi always emphasised self-control, brahmacharya and limiting the self. This is why his philosophy prioritised ‘need over greed’ and ‘internalising over externalising’. He even read varna dharma as a mode of self-limiting. Only later in life did he realise the more debilitating psycho-social dimensions.

What the Right is doing is lift the lid off guilt, apprehension and self-doubt. Even as social groups are at loggerheads with each other, even as castes are fighting each other, they are simultaneously are moving into the fold of the Right. This is how the language and articulation that the Right is providing has become the default language of the nation.

The latest in the repertoire is to link this deep sense of loss and wounded self with sexual fantasy, as in the case of Kashmiri women after the virtual abrogation of Article 370. Psychoanalysis was always deeply invested in libido as fundamental to how humans live, think and act. Gujarat in 2002 witnessed gory sexual violence. Such violence becomes a conduit between the inner struggle to connect to one’s own self and the concrete expression of majoritarian might.

Sexualising majoritarianism can play this psychological role more fundamentally than mob lynching or even genocide. It resonates against “civilisational humiliation” and the deeper revulsion against being regulated, disciplined or asked to find self-control (“in spite of being a majority”).

The veneer of guilt is washed away to feed a new kind of expression. The Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Zizek has argued that the rise of the Islamic State and the “sex slaves” they employ has to do with deeply regulated European societies that have got excessively governmentalised. In India, it has to do with historical wounds, primarily arising from being a caste-based society. Sexualising is by far the most concrete and urgent expression of militant majoritarianism having arrived.

Ajay Gudavarthy is Associate Professor, Centre for Political Studies, Jawaharlal Nehru University, Delhi. Views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.