What Can Kashmir’s Politicians Promise to Voters?

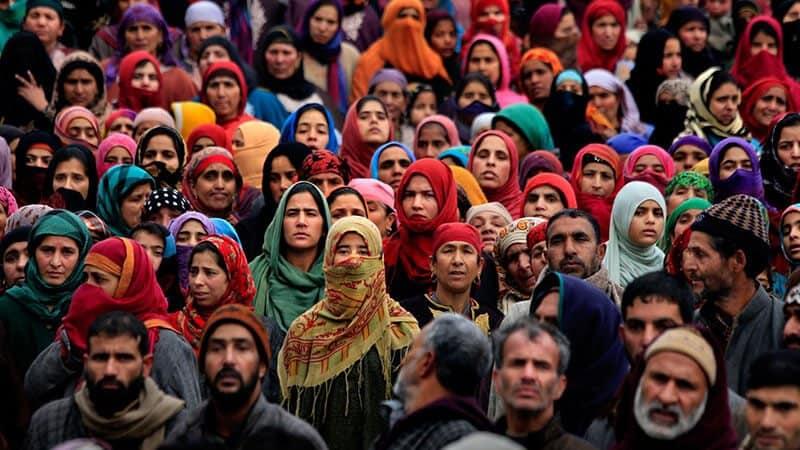

Representational image. | Image Courtesy: DU beat

After the Peoples Democratic Party government led by Mehbooba Mufti fell in June 2018, former Jammu and Kashmir chief minister and National Conference leader Omar Abdullah was all set to return to power. The general perception in the Valley, where I was at the time, was that the National Conference will return to power with a thumping majority. This was also apparent from the headlines, which were filled with news of leaders such as Basharat Bukhari, Peer Hussain, Mohammad Khalil Bandh and others switching loyalties from the PDP to the National Conference.

This perception was strengthened when National Conference president Farooq Abdullah won the Srinagar Lok Sabha seat in May 2019. But New Delhi had different plans. President’s rule was imposed in June 2019, sending the anxiety of political outfits in the Valley spiralling. This reflected in the boycott of the 2018 local body elections by the National Conference and the PDP. Both parties were irked by the suddenly uncertain position of Art. 35A of the Constitution. A bunch of petitions had been filed in the Supreme Court opposing this provision, which had guaranteed that property in Jammu and Kashmir could only be owned by state subjects.

Then 5 August 2019 changed it all. Leaders from the Valley across party lines were locked up. Not only were Articles 370 and 35A revoked, the statehood of Jammu and Kashmir was snatched away, leaving almost no window open for political outfits to participate in the political process.

But politics is an uncertain game. Even the most final-sounding statement can leave room for parties to fill or read between the lines. Delhi has left such a space open despite all its jubilant statements regarding on Art. 370. That space is for Jammu and Kashmir’s statehood to be restored, at some opportune time. The parties sensed an opportunity in this statement. They read it as the Centre telling them: ‘Do you need an issue to fight elections? Forget Articles 370 and 35A, but statehood is something which can be talked about.’

Lessons from the Delhi Accord:

The famous (infamous in the Valley) Delhi Accord of 1974, signed by Indira Gandhi and Sheikh Abdullah, was an important turning point. Though for years he had been adamant on returning Jammu and Kashmir to its pre-1953 status, Sheikh realised after the 1972 Indo-Pak war and resultant Shimla Agreement that he was not in a position to bend Indira Gandhi. He decided to compromise. After going in and out of jails for decades, Sheikh had learnt his lesson—make big claims when in the Valley and be almost mum when in Delhi.

The Delhi Accord was a clear win for the Centre, which effectively closed off any opportunity of a plebiscite in Jammu and Kashmir and sealed its fate as a constitutional unit of India. It is worth recalling that Sheikh’s politics during 1953-1974 revolved around the Plebiscite Front, a political outfit run by his trusted lieutenant Mirza Mohammad Afzal Beg. The Front was disbanded in 1975 right after Sheikh was decorated as Chief Minister although he had no MLA, nor a party. Yet he was given the same throne he had adorned once as ‘Prime Minister’.

Mirza Beg got an unceremonious exit and was charged with treachery, and Farooq Abdullah was declared Sheikh Abdullah’s successor. Farooq followed the same path as his father when he entered into the Rajiv-Farooq accord in 1986. Despite Farooq’s spirited bid to fight Indira Gandhi tooth and nail, he conceded defeat to her prodigy, Ghulam Mohammad Shah, while then Governor Jagmohan engaged in some well-orchestrated political manoeuvring. Farooq accepted in no uncertain terms that Kashmir cannot be governed without the support of Delhi. And now it seems that Omar Abdullah has also finally accepted this.

The Apni Party gambit:

Omar Abdullah’s recent statement should be read in a certain context. First, in March, a new party was launched by former PDP leader Syed Altaf Bukhari. Bukhari is said to have liaised between rebels and New Delhi when Ghulam Mohammad Shah had hatched a successful conspiracy against the Farooq Abdullah government in 1984, with help from Jagmohan. However, Bukhari’s political career started much later, in 2005, with Mufti Mohammad Sayeed’s PDP. He rose to prominence outside the Valley when it was proposed in winter 2018 that he head an unusual alliance—of the National Conference, the PDP and the Congress party, after the BJP had parted ways with PDP.

This surprise proposal was a last-ditch attempt to avert a perceived attack on the political independence of the Valley, but it failed because facsimile machines at the governor’s office apparently “malfunctioned”. Yet it seems that this former MLA—he was the richest legislator in the Valley—could not make inroads. With no political capital and discredited by allegations of corruption, he was in no position to make any gains. It seems that New Delhi has realised this—and though Bukhari was the first to throw its hat in the political ring in the new Union Territory of Kashmir—he has been unceremoniously dumped.

The undertones of Omar’s statements:

In a detailed interview published in a national daily, Omar has opened up for the first time after his release from detention in March. This interview should be read empathically. It is an interview of a leader who is not left with many options, who cannot tread to either extreme and whose favourite, the middle path, has been swept away. The special constitutional provisions were the only shield left with the National Conference or the PDP against the war cries of separatist forces. Autonomy was another plank which, though faded, still had symbolic resonance in the Valley. The abrogation of Art. 370 extirpated all of these.

The mainstream political outfits cannot shy away from elections unless their leaders decide to quit politics altogether. They cannot go into elections either, unless they have something they can promise people and something to showcase as achievements. The promise to battle for a pre-August 2019 status is always there. And Omar talks about this possibility when he says in the interview that his party is fighting against everything that was done on 5 August. He has said the fight will continue, but his party will not use undemocratic means.

Yet Omar knows very well that a return to August 2019 is almost unachievable. The democratic means available to him are limited to a legal battle against some unyielding proposals. So the only potentially attainable promise is of a return to statehood. New Delhi has indicated this possibility too, and for the time being, it can help Omar win back some of his party’s base. This is why Omar has said in no uncertain terms that he will not participate in the political process of a Union Territory; that statehood must be restored and taking it away is insulting and humiliating. He told another national daily as well that the National Conference will continue to fight what happened on 5 August, and that so long as Jammu and Kashmir is a Union Territory, he will not contest as chief minister.

It cannot be mere coincidence that Farooq Abdullah echoed the same view in his first interview after he was released from detention. His call for restoration of statehood and hope that the Supreme Court would strike out the reading down of Art. 370 is a clear indication of the future path for the National Conference.

Moving ahead is a prerequisite for any political party. Every party needs a stepping stone, a series of goals and achievements. Omar claimed that these stepping stones are a personal goal—and technically they are, for the National Conference party and the Abdullah family have almost been synonymous in the Valley for seven decades. Omar inherited leadership from his father and grandfather. Now he needs to earn credibility to carry it forward.

The new deal:

Soon after Omar’s public statements, cracks appeared in his party. These hark back to the reactions of ordinary people when Farooq avoided mentioning Art. 370 during his interactions with journalists on 6 October, after he had met his party’s leaders during his detention. The silence on Art. 370 had set the streets of Srinagar abuzz with rumours of a “deal”. These rumours have resurfaced.

The resignation of ex-minister and powerful Shi’a leader Aga Syed Ruhullah from the post of spokesperson is the first sign of fissures within the National Conference. Aga does not only command respect and political power in central Kashmir, he is also considered close to Omar. He is among the few who had publicly favoured a street fight against revocation of Jammu and Kashmir’s special status, while Omar has made it very clear that he will not support any such movement and prefers a legal battle instead.

The continued detention of Mehbooba Mufti also gives credence to talks about a deal between New Delhi and National Conference leaders. The Muftis and the Abdullahs were prime signatories of the Gupkar Declaration signed in August 2019. In this Declaration, named after an all-party meeting held at Farooq Abdullah’s residence, all attendees resolved to fight the revocation of special status. Now there are suggestions that the release of the Abdullahs and continued detention of Mehbooba Mufti means more than a legal battle is at play. Social media is abuzz with the speculation that while the Abdullahs have decided to go down some middle path, Mufti has not. Unlike the previous Rajiv-Farooq accord, there are no written document to go by this time. That is why the statements of the father-son duo have naturally fuelled speculation.

The way ahead:

Here lie the contradictions interwoven in Kashmiri society, which have become more prominent in the post-5 August scenario. With Articles 370 and 35A gone, separatists are propagating the claim that mainstream leaders are mere pawns of Delhi. With a new delimitation in the offing, the Valley may lose its prominence in the state’s electoral politics. The new domicile rules have left even Jammu feeling betrayed in a game that it once welcomed. With no talk about the status of tribes yet, discontent is simmering in Ladakh as well. Growing discontent in the Valley has left the resident Kashmiri Pandits feeling uncomfortable too. Plus no specific plan has been drawn up for their return to the Valley, so the Jammu-based Pandits are also rethinking their position on Art. 370.

It is in the air that elections may be held once Covid-19 subsides in the Valley. But the important question is, who will contest them and will the voters participate, especially in the Valley? It is true Pakistan could not get much support from the international community over the revocation of Kashmir’s special status, but the state cannot be kept under President’s rule forever. Some political discourse has to start from somewhere.

Omar’s move should be analysed with reference to these contradictions first: deal or no deal, he is thinking of the future. A future marred with thousands of questions and with no certain answers yet. He is probably thinking that if delimitation can be halted and statehood restored, then Kashmir can do without Art. 370. That the emotional attachment to the special status will fade just as the attachment to the old title of Prime Minister faded.

But he and Delhi have to remember that the discontent of Kashmiris has its roots in the Delhi Accord. Leaders of the insurgency such as Ashfaq Majeed Wani were products of this discontent. The Delhi Accord established democracy in the short run, and Sheikh established his authority through elections, but the anger of unsatisfied youths resulted in a bloody civil war after the much-discussed Assembly election of 1986, which were also an outcome of another accord between Rajiv Gandhi and Farooq Abdullah.

Short term gains are lucrative but to quote George Santayana, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

Ashok Kumar Pandey is the author of Kashmirnama and Kashmir and Kashmiri Pandits. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.