What India Can Learn from Myanmar’s Citizenship Law

“Justice is the first virtue of social institutions, as truth is of the system of thought. A theory however elegant and economical must be rejected or revised if it is untrue; likewise, laws and institutions no matter how efficient and well-arranged must be reformed or abolished if they are unjust.”

This statement of John Rawls, from his book, A Theory of Justice, would strike a chord with most present-day thinkers. For, though people may disagree over ideas of justice, no reasonable person would hold the belief that unjust institutions have a place in society.

On 11 December 2019, Parliament passed the Citizenship Amendment Act (CAA) 2019, which has polarised the nation and put citizens in two competing camps. Yet, interestingly, both its proponents and opponents claim to hold justice at the core of their argument.

For a better understanding of this conundrum, we must consider what CAA has changed in India’s notion of citizenship.

Indian citizenship is regulated by the Citizenship Act, 1955 (CA 1955). It specifies five methods to acquire citizenship: by birth in India, by descent, through registration, by naturalisation and by incorporation of the resident’s territory into India. An illegal migrant, that is, a foreigner who either enters India without valid travel documents or extends his or her stay after they have expired—is prohibited from acquiring Indian citizenship by section 2(1)(b).

CAA brings a major change with respect to citizenship through naturalisation, as it states that some illegal migrants, that is, Hindus, Sikhs, Buddhists, Jains, Parsis and Christians from Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan, who came to India on or before 31 December 2014 shall not be treated as illegal migrants, and qualify for citizenship through naturalisation. Also, the third schedule of the CA 1955 has been amended to lower the minimum required period of residence from 11 to 5 years for citizenship through naturalisation.

The government argues that these provisions will provide relief to persecuted minorities of the listed countries. However, CAA and its ripple effect can also have dire consequences.

All lists are exclusionary in nature in that when they keep some items inside, they keep others outside. CAA creates two such lists.

In the first list, which comprises six religion-based communities, the Parliament has struck off the Muslim community. The government’s argument is that the second list consists of Islamic states, where, allegedly, religious persecution of the majority community is out of question. However, the first list also excludes many other smaller religious communities, thereby creating an irony—a government whose heart bleeds for persecuted minorities ends up excluding persecuted minorities.

If merely being a minority makes a community vulnerable in the country they live in, then it would stand to reason that the smaller a community, the greater is their need for protection.

The obvious question is why the government has put out such a list of countries or communities—why not just insert a legal provision that extends protection to all religious minorities? After all, no common thread binds the listed religions. With Parsis and Christians included, the first list is not even of ‘Indic’ religions.

Interestingly, the continuous persecution of Ahmadiyya (a Muslim community) in Pakistan, has cast further doubt over the utility of such lists. Their persecution is an indication that in an extremist society following a different religion is as dangerous as following the same religion, but differently.

Pakistan has officially declared the Ahmadiyya sect as non-Muslim, for they do not consider Muhammad to be the final prophet. It is the only country to have done so. The tricky question is, if India had decided to fast-track Ahmadiyya citizenship, as it has for the others on its list, how would the law have referred to them? Calling the Ahmadiyyas “Muslim” would have made the first list nonsensical. However, referring to them as “Ahmadiyya” would have amounted to accepting them as non-Muslim.

Now, India is home to around one million Ahmadiyya. Many academic works have recorded that the community is not alien to India, including South Asia in the World: An Introduction, edited by Susan Snow Wadley. As well, many Ahmadiyyas who were facing persecution in Pakistan have sought refuge in India. One can therefore draw the conclusion that the CAA would have arguably been more just and effective, and less discriminatory, without the first list referring to communities. Again, in the list of religions, one obvious miss is irreligious people and atheists, who have also been persecuted time and again. Their inclusion in the CAA or simply a listless CAA would have brought relief to them, and to many more people.

The second list in the CAA is of three neighbouring countries, namely, Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan. India has nine neighbours, seven of which (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, China, Myanmar, Nepal and Pakistan) have land borders with her while the other two are separated by the sea (the Maldives and Sri Lanka). The rationale behind excluding six and including three of these countries needs examination, though the government has taken no official stand on this. For instance, it conveniently skipped answering the issue in its own FAQ.

Yet, one can discern two motives:

The first justification revolves around providing humanitarian assistance to the residents of Undivided India as per the Government of India Act, 1935. It has been argued that India owes a moral obligation towards the minorities in these countries, for they were being persecuted after being left on the wrong side of a rather arbitrarily-created border. However, this reasoning cannot sustain, as Afghanistan was not a part of Undivided India.

The second justification is manifestly questionable, for it states that the list comprises three “Muslim” countries, but it leaves the Maldives—also a Muslim country—out. The apparent logic is that the listed Muslim countries witness more religious persecution, but this stereotypes the listed countries.

It views Muslims from the prism of popular sentiment, without providing objective criteria or data to back the claim.

The proponents of CAA have been adamant in claiming that it strives to meet a moral obligation towards certain persecuted religious minorities and not to discriminate against any community or individuals. They argue that a flawed CAA is better than none. To put it in medical jargon, the argument is that even if CAA is no panacea it does not mean that it is a bad prescription. In fact, it is a good enough antidote to save a large number of people. Nothing could be farther from the truth, and the CAA, instead of an antidote, could end up being an emperor of maladies.

Every substantive law comes with a purpose, usually to resolve certain problems. The government claims that the CAA’s definite purpose is to provide early citizenship to certain persecuted minorities—though “persecution” or “religious persecution” are not mentioned in the act itself. Astonishingly, this conflict between claim and reality is rarely, if ever, mentioned in the public discourse.

This silence is reminiscent of an incident in the popular work of fiction, The Curious Case of the Dog in the Night-time:

Gregory [Scotland Yard detective]: Is there any other point to which you would wish to draw my attention?

Holmes: To the curious incident of the dog in the night-time.

Gregory: The dog did nothing in the night-time.

Holmes: That was the curious incident.

Silence in the CAA simply gives officials discretion in awarding citizenship. In other words, the CAA licenses the government to grant citizenship rights to individuals from the six listed communities coming from the three listed neighbouring territories, whether or not they are persecuted. Warson Shire’s words, “No one leaves home unless home is the mouth of a shark” may justify this situation, but the same phrase can also be used by opponents of the CAA. This is because CAA was proposed and enacted at a time when millions of Rohingya Muslims had fled Myanmar, a theocratic Buddhist state, after a long period of atrocities.

The Rohingya exodus has been called the gravest of crimes under international law by a Human Rights Council Report.

More than seven decades after Partition, discrimination against minorities and violation of their human rights remains a consistent feature in the listed countries, especially Bangladesh and Pakistan. Hence, despite its shortcomings, CAA may appear to be a necessary safeguard for refugees. This notion, however, needs to be parsed. First, the Rohingya question entered the public discourse in 2017, when security operations in Myanmar forced more than 6 million of them to flee. The same year, the Indian government proposed deporting approximately 40,000 Rohingya refugees back to Myanmar. This violates the international principle of non-refoulement that forbids sending a person to their home state if they have a “well-founded fear of persecution” there.

True, India is not a signatory to 1951 Refugee Convention, which makes non-refoulement inapplicable to it, but the fact remains that the CAA has failed to provide Rohingyas relief when it ought to have.

The case of the Rohingya community is relevant to assessing the CAA, because the history of their statelessness has to be read alongside Myanmar’s discriminatory 1982 Citizenship Law. This law, and the sequence of events in Myanmar preceding and following its enactment, holds warnings and lessons for India. Myanmar’s dubious citizenship law violates international humanitarian law violations and resulted in the Rohingya crisis. This makes it essential to better understand CAA and its potential impact on the Indian politics and society.

Contrary to the popular view in Myanmar, evidence suggests that Bengali Muslim settlements in Arakan (now Rakhine state in Myanmar) date back to the 1430s. This is recorded in the Development of a Muslim Enclave in Arakan (Rakhine) State of Burma (Myanmar), penned by researcher Aye Chan, published in the third volume of the SOAS Bulletin of Burma Research in autumn 2005. According to it, Arakan was independent until 1784, when it was conquered by and incorporated into the Burmese empire. Burma was conquered by Britain in 1824 and ruled as a part of British India.

During this period, many Bengali Muslims entered Burma as migrant workers, tripling the country’s Muslim population.

The Burmese resented what they saw as an incursion of uninvited workers. Although Britain promised the Rohingya people an autonomous state, in exchange for their help in World War II, this was never done. Thus Burma gained independence in 1948 with social disharmony at its core—a legacy of British colonialism in many other parts—which worsened over time.

The 1947 Constitution and the 1948 Union Citizenship Act of newly-independent Myanmar [then Burma] provided a relatively inclusive citizenship framework. Myanmar’s first Prime Minister, U Nu, is reported to have referred to the Rohingya by name in a 1954 radio address, as “… our nationals, our brethren”. However, a narrative took root that most Muslims in Rakhine state are illegal Bengali immigrants. There was increasing emphasis on the importance of “national races” in Myanmar’s public discourse, and the need to deport alleged aliens became popular.

Then arrives the 1982 Burma Citizenship Law, along with its 1983 procedures, which created three distinct classes of citizens. Full citizenship was primarily reserved for “national ethnic groups” and did not include the Rohingya, people of Chinese, Indian or Nepali descent. Associate citizenship was for those whose application for citizenship under the 1948 citizenship law was pending when the 1982 law came into force. And naturalised citizenship was provided for, for people who could provide “conclusive evidence” of their entry into Myanmar and residence there prior to 1948, and to their children.

Despite this manifestly discriminatory framework, Rohingya were not necessarily fully excluded by this idea of citizenship. The Constitution and law provided for existing citizens to remain citizens. Many Rohingya would also qualify for “associate” or “naturalised” citizenship. Moreover, the third-generation offspring of the Rohingya would have been full citizens by now. The law also explicitly authorises the state to confer citizenship to any person “in the interests of the state”.7

In reality, however, the law was implemented in a discriminatory and arbitrary manner.

In a nationwide citizenship scrutiny exercise, the National Registration Card (NRC)—a document received by citizens during the 1950s—had to be turned in and replaced by a Citizenship Scrutiny Card (CSC). Rohingyas were reportedly refused a CSC, even when they met the citizenship conditions. This could happen because the 1982 law provides broad discretion to officials to arbitrarily decide citizenship.8

The Rohingya, thus rendered vulnerable to discrimination, marginalisation and denial of basic human rights, were forced to flee Myanmar. There were at least four previous waves of displacement in 1978, 1991-1992 and 2016, but the world and international organisations showed little interest prior to the security operations of August 2017. Some 655,500 Rohingya residents had fled targeted killings and widespread human rights violations by the end of 2017.

To summarise, throwing off the yoke of British colonialism—which had left Myanmar marked by hostility between the ‘indigenous’ (especially Buddhist) population and the Muslims—was defeated to an extent by a rather inclusive Constitution and citizenship law. But divisive forces such as the 969 Movement led by Buddhist monks filled the public discourse with anti-Muslim rhetoric. They established a narrative of Muslim “takeover” of Myanmar through marriage and conversion, notwithstanding that the Muslim population in Myanmar has been estimated at only around 4%.

In 2016, the government released the Census data related to religion showing that 2.3% of the enumerated population identified as Muslim, a drop from 3.9% in 1983.

Nobody would miss the remarkable similarities between India and Myanmar highlighted in this discussion. The history of Myanmar is critical to assess the CAA—just as the history of persecution in Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan is. We know from the works of Aye Chan (referred to above) and others, such as Khalid Koser in International Migration: A Very Short Introduction (published by Oxford University Press in 2016) that migration, a ubiquitous phenomenon, poses a dilemma for almost every nation. We also know that when thousands of Rohingya were seeking refuge in India, the Indian government decided to offer citizenship to every other refugee but them—making it a patently discriminatory law.

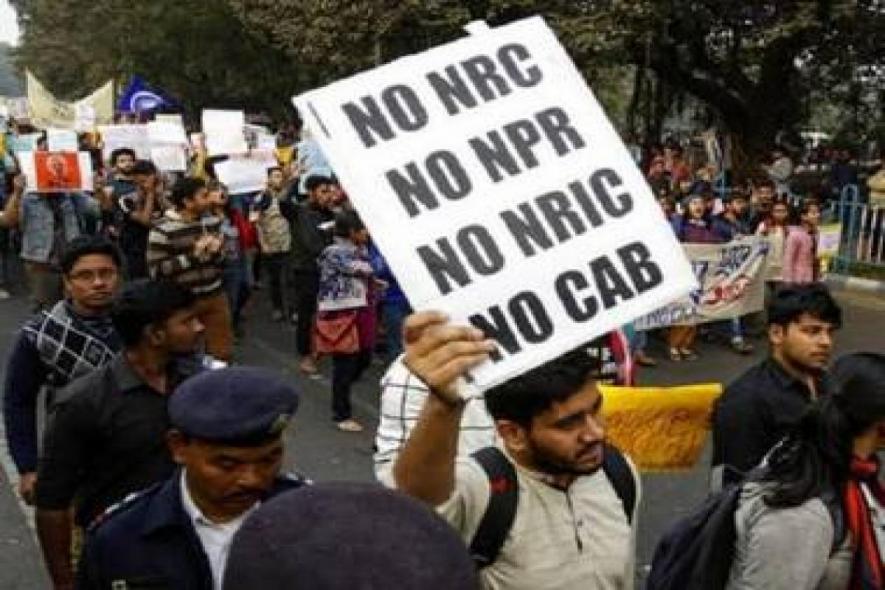

The famous chronology of events manifests the government’s motive all the more explicitly. The National Register of Citizenship (NRC) conducted in Assam as part of a Supreme Court-monitored exercise cost Rs 1,220 crore and ten years, but turned out a futile exercise because of criticism over its methodology and because a large, though unconfirmed, number of those excluded from citizenship are Hindus. This earned the exercise the moniker of “anti-Hindu”.

For now, talk of deporting those excluded by the NRC is on hold in Assam. However, now, the CAA and the agenda to hold a nationwide NRC in future has entered the discussions.

While the nation awaits the NRC, even if people from the six listed communities fail to prove their citizenship, CAA would potentially re-include them as citizens. CAA also improves the chances of inclusion of those Hindus who were left behind by the Assam NRC. The excluded Muslims or atheists, however, do not have this protection. This is why many social groups are fearful of disenfranchisement in future.

Seen from the perspective of the excluded, the CAA is not a safety net but a sieve that would filter out definite communities and individuals and create a new class of stateless citizens.

This would explain the nationwide protests against CAA with students at its centre despite a good amount of public support for the amended citizenship law. Surely, an awareness of atrocities inflicted in the listed neighbouring countries, especially against Hindus, creates support for the CAA in India. However, their concomitant refusal to even consider extending CAA to, for instance, the Rohingya, Ahmadiyya or Baloch communities, belies this. In fact, they invariably wish for the non-listed communities currently resident in India to be deported. Apparently, the only barrier to the deportation of 40,000 Rohingya is a 2017 petition against it, pending in the Supreme Court.

Poor past experiences of Indians with Pakistan and a narrative of narrow nationalism contribute to this prejudice and make sensitivity towards Ahmadiyya, Baloch or Rohingya people virtually impossible. That said, India has faced several acute refugee problems through its modern history, yet it has:

• No specific legislation to deal with the refugee problem

• No national system to determine refugee status

• No clear definition of who is a ‘refugee’

• No national asylum policy

Migration related issued have been handled in India either politically or administratively, with the sole exception of the Rehabilitation Finance Administration Act of 1948, framed to cope with Partition-era influx of refugees. The Constitution, the Foreigners Act of 1946, the Registration of Foreigners Act of 1939, the Extradition Act of 1962 and a few court verdicts make up the rest of this piecemeal legal framework. [India is not a signatory to the 1951 Refugee Convention nor to the 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of Refugees.]

Hence, there is a legal vacuum, which has been filled largely by arbitrariness. The fate of thousands of immigrants depends on whims and fancies of the state with ideologies, electoral promises, global, national and regional politics colluding to smokescreen what are really random decisions, of which fast-tracked citizenship and forced deportation are instances.

Other consequences of these legal lacunae are mostly imperceptible, for instance, unclear legal status and lack of uniform documentation has limited refugee’s access to essential services and livelihoods in India. Some have been able to find work in the informal sector, but most, especially women, are at the mercy of traffickers and exploitation. India needs a comprehensive legal framework on refugees. Even those who favour CAA should ask for it, as government policies are as fickle as parties in power.

Stateless people are arguably the most vulnerable people on earth. If granting early citizenship is like giving privilege, providing asylum is like providing relief and forced expulsion is like pushing people into an abyss. India is doing all of this, that too without any predetermined rule of law. Its criteria are mostly morally arbitrary in nature. Morally arbitrary because no one chooses the religion or region they are born in, and any criteria that gives or denies relief based on these basis is arbitrary and therefore unjust.

Today, all sides are continuously rethinking the idea of India. This debate could prove salubrious for democracy, for all nations must determine what they stand for. Yet, remember Rawls—without justice at its core nothing will be worth having.

The author is a lawyer and postgraduate in political science from Lucknow University. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.