Abdul Ghaffar Khan: Freedom Fighter, Gandhian, Pacifist, Muslim and Pakhtun

January is an important month for Indians. Apart from the English new year, 26 January marks the day when the Constitution was adopted, and 30 January marks the death anniversary of Mahatma Gandhi, who was shot dead by Nathuram Godse, a Hindutva fanatic. Very few remember that 20 January marks the death anniversary of another Gandhian giant whose politics rose above communalism and was singularly focussed against British imperialism’s purloining of India. He was Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, a.k.a. Bacha Khan and the Frontier Gandhi. He was named Badshah Khan at twenty-six by the members of his tribe when his father died.

Khan was born on 6 February 1890, two and a half months after Jawaharlal Nehru, in the village of Utmanzai, what is now a small town near Peshawar in today’s Pakistan, then British India. His father was Behram Khan, the leader of the Muhammadzai tribe who owned prosperous agricultural lands and took pride in speaking the purest accent of Pashto, allowing the tribe to remember traditions bequeathed upon them by their rich history.

Badshah Khan, too represented the best among the Pathans. As a young boy, he left his high school final exams, aspiring to join ‘The Guides’, a corps composed of Sikhs and Pathans. He expected this would allow him to become an officer in the British Indian army. But when he witnessed British racism against a fellow Pathan in the corps, he resigned from the Guides, refusing commission much to his father’s displeasure. His father did not harbour an intense anti-British feeling because his uncle served for the British during the 1857 revolt and held the local activities of the British such as the building of hospitals and schools in good stead.

In 1910 this led Badshah Khan to open a network of schools in his area. He envisaged education to carry reforms among the Pathans who would otherwise spend lavishly on weddings and funerals or remain perennially garrulous towards other tribespeople on petty issues. He christened them as azad madrassas. He also espoused the cause of the education of women wholeheartedly. Today, a predominantly Pashtun Taliban is hell-bent on not allowing girls to study, their only devious concession that an opaque purdah should strictly separate them from the male folks. Ghaffar Khan sent his teenage daughter Mehr Taj to study in England in 1932!

For a very long time, the frontier province had remained unaffected by the twists and turns of colonial chicanery. For a very long time, the frontier province had remained unaffected by the twists and turns of colonial chicanery. During the Swadeshi movement when the British view of the Muslims underwent a sea change—from the dangerous fanatical community of the 1857 Revolt to a dependable rough diamond full of martial virtues vis-à-vis the conniving Hindu, leading to the formation of the Muslim League—the 93%-strong frontier Pashtuns were least affected. And when colonial largesse came in the form of separate electorates through the Morley-Minto reforms of 1909, again, the frontier province remained politically unstimulated.

Even during the Montague-Chelmsford reforms, when the British decided to share provincial power with Indians, the north-western frontier province was excluded from the purview of the reforms. As a result, the Pashtuns remained sans franchisee, elections, and legislature.

It was only after the First World War that the land of the Pashtuns began to shake with an intense anti-imperial sentiment. The tipping point came with the Rowlatt Act. The act resembled the much-hated Frontier Crimes Regulations of 1903, under which any person could be detained and sentenced for life without being brought before the court of law or the right to counsel. Khan harboured consternation for the existing Regulation and took the opportunity to oppose by calling for a meeting in Utmanzai on 6 April 1919, the day when meetings were organised throughout India on Gandhi’s call. The huge and unexpected attendance at the meeting trembled the British to the core leading the police to arrest Khan, be fettered, and driven to Peshawar, followed by a presentation at a court whilst the Khan’s fettered feet bled.

It was during one of these many prison terms that Khan got the opportunity to read the Bible, the Geeta, and the Guru Granth Sahib which paved the way for his lifelong commitment to inter-faith harmony. The best instance of this came when a local cleric implored him about the possibility of lasting peace with the idol-worshipping Hindus, Khan said, “If they are idol worshippers, what are we? What is the worship of tombs? How are they any the less devotees of God when I know that they believe in one God? And why do you despair of Hindu-Muslim unity? Look at the fields over there. The grain sowed therein has to remain in the earth for a certain time, then it sprouts and, in due time, yields hundreds of its kind. The same is the case about every effort in a good cause.”

Interestingly, Khan once accompanied Gandhi to Banaras to inaugurate the shrine of ‘Mother India’, a huge relief map of India engraved on marble. He made it a point to join the recitation of Vedic incantations, and while doing so, Khan delightfully recalled that in the old days, mosques were open to people of all religions and hoped the new shrine would fulfil the noble purpose of a commonplace of worship for all.

Like other Muslims of his time, he too was taken in by the pan-Islamic Khilafat movement. He even made the famous hijrat to Afghanistan under the false assumption that India had become dar-ul-harb, land of war. His hopes were dashed when he came to know that the Pathan King of Afghanistan did not speak Pashto and commanded him to go back with his followers. But just as the dialectics of history led some of those dejected hijratis to establish the Communist Party of India in 1920, Badshah Khan returned as a hardcore nationalist admitting later that ‘the hijrat did enormous damage to the Pathans’.

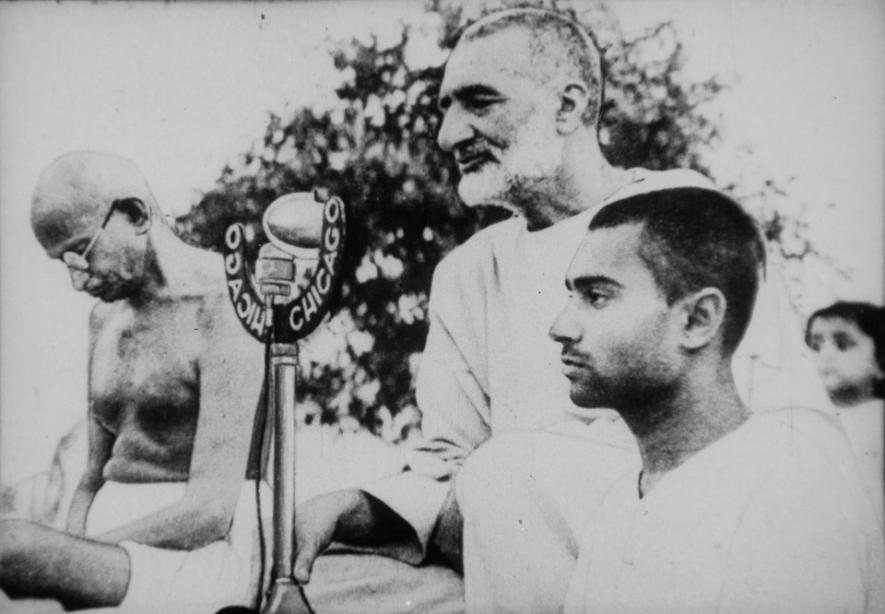

The Non-Cooperation Movement drew Khan to the Congress session in Nagpur (1920). However, he could not meet Gandhi in person, only managing to see him from a distance. It was only at the 1929 Lucknow session of the Congress that he met Gandhi and Nehru. In September 1926, Khan established the Khudai Khitmatgars, an overwhelmingly Pashtun corps but whose membership was open to Hindus, Christians, and Sikhs. The members were also called Red Shirts but unlike the fascist Black Shirts and the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh White Shirts, they did not carry a weapon, not even a lathi. They only spread the message of peace, unity, and non-violence.

It was during the Lahore resolution of purna swaraj (complete independence) and the salt march that Khan became most proactive. His subsequent arrest led to the killing of two to three hundred Khudai Khitmatgars. The violence led him to adopt the creed of non-violence in toto. On Gandhi’s call, he went to Bardoli, where he linked non-violence to Islam. In a meeting presided by Kasturba Bai, Khan said, “There is nothing surprising in a Musalman or a Pathan like me subscribing to non-violence. It is not a new creed. It was followed fourteen hundred years ago by the Prophet, all the time he was in Mecca...But we had so far forgotten it that when Mahatma Gandhi placed it before us, we thought he was sponsoring a new creed or a novel weapon”.

Rajmohan Gandhi, in his biographical study Ghaffar Khan: Nonviolent Badshah of the Pashtuns, notes that Badshah Khan preferred the Pashto translation adam tashaddud meaning ‘no-violence’ against the in-vogue ‘non-violence’. It made Khan’s variant of the creed a shade deeper than that of Gandhi, who did not bother much of its linguistic aspects.

Soon Khan became a leading light of the Congress. He merged the Khudai Khitmatgars with Congress so that the Frontier Congress and the Khitmatgars could be one organisation. He was also distinguished from other Muslim leaders in the Congress and League on one important front—a deep and personal sympathy for the poor and the oppressed. It was unimaginable to think of Jinnah, a super-rich lawyer with a distaste for masses and mass politics, or Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, a highly learned theologian, to live among the poor and the lower castes in the sweeper’s colonies of the Valmiki’s in Delhi. Khan’s spell in jail wherein only sweepers were allowed to serve him food and visit his cell for cleaning made him a lifelong ally of the lower castes.

D.G. Tendulkar, in his biographical sketch of Khan, Abdul Ghaffar Khan: Faith is Battle, records that during the crucial Simla Conference (1946), on Gandhi’s prodding, Badshah Khan visited the sweepers’ colony in Simla followed by a visit to a similar settlement in Delhi. Khan reported to Gandhi that the conditions were not fit even for animals to live. The next morning, the sweepers visited Khan with a long tale of woe, leading him to implore the people of Simla that it was their bounden duty to look into their grievances and have them addressed immediately.

During the 1937 election, Congress won 15 out of 36 seats reserved for Muslims in the north-western province, while the Muslim League failed to win a single seat. Badshah Khan did not even campaign for the elections because of his apprehension that the worldly temptations that come with office would have a corrosive impact on the moral rectitude of the Khudai Khitmatgars. However, after the left-wing and the right-wing were assuaged by Gandhi, the Congress decided to take up power where it had won majority leading Dr Khan Sahib, Badshah Khan’s elder brother, to become the Chief Minister of the province.

During the 1940s, when the rotten stench of communalism started reeking in India, Khan held his ground. After the horrors of Direct Action Day and the sordid celebration of khooni mushairas by the League during the 1946 election campaign wherein bricks from mosques desecrated by Hindus, damaged copies of Koran were flaunted, and Muslims were given a choice between the Gita and the Koran, Badshah Khan abstained from such egregious political tussles and personally joined Gandhi in the riot-hit areas. On the eve of independence, Khan spent three and a half months out of five away from Peshawar and Delhi alike because he did not think that his place was among those who were fighting and bargaining for power while the country was on fire. In a letter to Gandhi, the realist Patel implored Khan’s absence in Peshawar, where the Muslim League was creating trouble. Ironically, Gandhi himself was in Bihar attending to the riot victims.

As Partition became imminent, Khan was the only one among four of the members of the Congress Working Committee along with Gandhi, Jayaprakash Narayan, and Ram Manohar Lohia, who voted against the partition plan. Tendulkar records that on the occasion of voting when Maulana Azad was sitting next to Khan, he told the latter to join the Muslim League. Khan immediately rushed out in disgust, sat on the staircase, and uttered the word of repentance twice ‘tobah, tobah’. (Aijaz Ahmad, ‘Frontier Gandhi: Reflections on Muslim Nationalism in India’. Social Scientist.)

Left alone in a politically hostile Pakistan, Khan did not mend his politics to suit the circumstances. After becoming the member of the Constituent Assembly of Pakistan, just like Gandhi had demanded of the Congress in India, Badshah Khan proposed that with the creation of Pakistan, the Muslim League had achieved its goal and should now dissolve itself. He wanted it to pave the way to form entirely new kinds of parties that would not take office but would devote themselves to the service of the nation. Unfortunately, nothing came of the advice. On the contrary, Pakistani rulers were to keep him in prison for fifteen of the first eighteen years after Partition, including in solitary confinement.

Badshah Khan lived a long life dying at the ripe age of ninety-eight. All his life, he was the epitome of honesty, selflessness, and non-violence. A majority of Indians and Pakistanis, or for that matter, South Asians, have forgotten him to their peril. Today when the forces of religious fundamentalism are raging through the region engulfing politics, culture, and day-to-day life, we must remember the Badshah and his teachings more than ever

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.