Run for Your Life. Running is Life

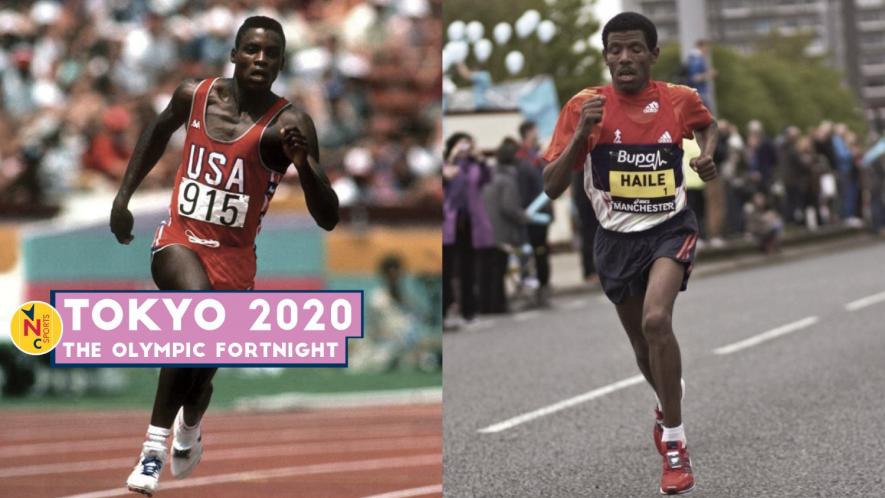

Carl Lewis and Haile Gebrselassie, two different champions, with two different running philosophies — one looking at it as an art form, the other seeing it as tech that facilitates human progress towards near perfection.

We all have a pre ordained distance to run in life. Beating fate is next to impossible. Then again, destiny also happens to be a sum total of all things man made. So we run in life — at times away — sometimes toward someone or something. We also run races. The sweat on the marathon courses or tracks becoming for us a physical embodiment of the metaphysical run in life.

They say there is a distance for all of us. We are talking about the universality or versatility of running as a sport. It represents the unity of motion while displaying the rich diversity of human existence — from the psyche and physical attributes to the muscle type. Running, in essence, is the idealistic preamble to egalitarian values in sport. It embodies many things the Olympic movement stood for when it was conceptualized. Running accords the same scope of expression to a 100 metre sprinter as well as an ultra marathoner. Just that the parameters differ, the time and space variables differ.

“Running is life,” they said...

In two separate conversations — a couple of years apart — two of the greatest runners in human history said the exact same words to me, equating running to life and life to running, intertwining them in a symmetric double helix, like the schematics of our DNA.

Click | For more from ‘Tokyo 2020, The Olympic Fortnight’ series

Carl Lewis and Haile Gebrselassie are poles apart. They come from different continents, and running for them — whenever it began and wherever the journey took them — meant different things. They had and have different lives. The distances they run fall on the opposite end of the mainstream athletics spectrum. Lewis, the long jumper turned sprinter; Gebselassie, the middle distance runner turned marathoner. Their difference in physique — which rather beautifully correlates with their personalities — stems from the type of races they have run in life. Much like how the races we have endured in life defines our bearing.

Running, as an exertion, a means of expression, an avenue to make a living, and a path towards making a mark in history, all meant different things for them.

“Running is life for me. I cannot explain how happy I feel when I run,” Gebrselassie said.

It was 2013. At the time, the Ethiopian, after missing out on the London Olympics due to injury, was contemplating life after running. And he admitted, rather happily, that the more he thinks of such a life, the more he realises it is impossible to stay away. So, he is just mulling what distance he would run. He had made that choice earlier as well, while leaving the track and his favourite 10km for the marathon, listening to his middle-aged body.

“Running is an art form.... And I express myself through running,” the two-time Olympic gold medalist said. “Like many things in life, you start to run as a kid. But running is one thing you cannot stop. After a while, you will stop competing, but you don’t stop running for good. For me, running is like any other daily routine like eating or sleeping. Sometimes, when I don’t train, the whole day I have this feeling I am missing something. Then, when I look back, I realise that I did not run that day and that was what was bothering me. Running is in my body now, you can say.”

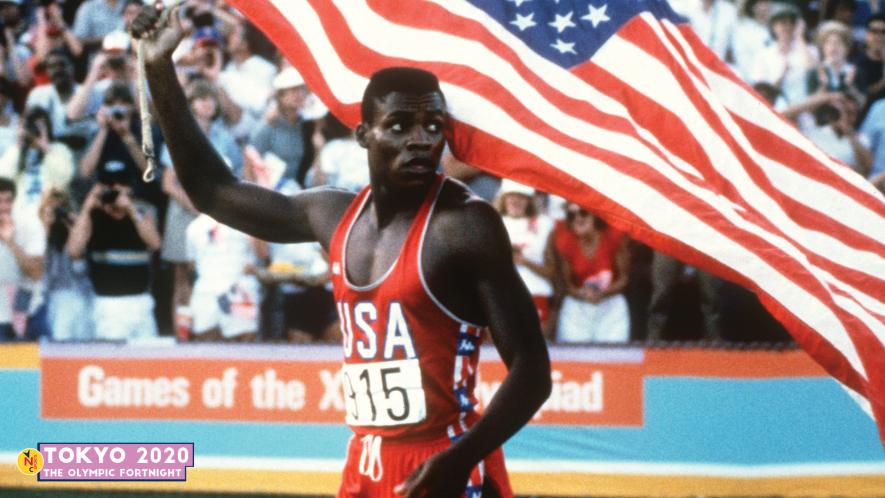

Lewis, the star of the track half a generation before Gebrselassie, was happily retired when we met in 2015. Barring the occasional verbal joust with Usain Bolt, the former monarch seemed at ease with his position in history, as the man who revolutionised athletics, and made it ready for professionalism, for the likes of Bolt.

The American, governed no doubt by the demands of sprinting as much as by his personality and the culture he hails from, looked at running differently. He enjoyed the raw pace. Also, despite being an extrovert — the face of athletics and big-spending ad campaigns at one point — he enjoyed the loneliness, helped perhaps with the knowledge that it will only last less than 10 seconds.

Also Read | Name: Indian Football Team; Place of Birth: The Olympics

“Oh, I could run fast. I could always run fast,” he said. “I didn’t go into a race to win. I went in to run fast. I went in with a certain time in mind. I knew what I had to do. My point was that if I run 9.90, I will win in any case. So my mind was set to run 9.90. I just stayed in my lane, which is my world, and ran 9.90.”

Beyond the obsession with the nanosecond, Lewis — nine time Olympic gold medalist and a former world record holder in the 100 metres — believed in reaching and touching the true potential of the body and will, and returning to tell the tale. He believed running had the ability to better himself — where he is and what he is — by sheer pace, by breaking records. It was for him an avenue to push a personal envelope as much as that of the sport.

“Why do people run faster? You want to outrun the previous best time,” he said. “That basic urge will never go away. Everyone says there is a limit to the human body. The reality is that if there is a distance out there, a time out there, a throw out there to beat, someone’s going to try and, eventually, succeed. I don’t believe there is a limit to the human body. Someone will always be bettering what others did.”

Two different champions, with two different running philosophies — one looking at it as an art form to enrich his life, the other seeing it as tech that facilitates human progress towards near perfection on the running track.

The differences end there, though. Running binds them in a way which negates many of the variables their races bring in. Big stage, high stakes competitive running ties them together in an extremely objective process. No surprises there. After all, be it art or science, it is the process which an artist or a scientist traverses through to bring out beauty or a revolution.

“When you run a marathon, if you are running for a record, you always focus on time,” said Gebrselassie. “I break the races kilometre by kilometre and keep an eye on the clock. The calculation has to be there. Someone has to keep a tab of that and keep you informed. If you are attempting a world record, you have to complete every kilometre in around 2 minutes and 53 seconds (then).” Now the break-up is even lesser, thanks to Eliud Kiphchoge.

“Marathons are close and very fast. Someone attempting a world record has to be in the game from the very first stride. But, if you are eyeing just a win, you have to think of the opponents and plan to be in the lead group, share pacing duties and then push for victory,” he added. The process and tactics, and the stress on execution to the point of perfection evident in his words.

Lewis was an embodiment of perfection of technique, both while sprinting and while long jumping. His process revolved around counts, isolation, attaining a perfect running form, and securing his space in his lane. Once he secured his zone in his lane — his world — he knew that 10 seconds later, he would secure his spot in history.

Also Read | NBA Returns; Players Show Solidarity With Movement to Curb Racial Injustice

He chose to explain sprinting first even though he kept saying in the conversation that he is a long jumper at heart. Perhaps it is a reflection on the different stakes these two events carry. 100 metres is where kings run!

“In sprints, you have to get the angle right, your head can’t come up at the start, your body has to be in the correct position. You train and train till you reach perfection in motion. In the 100 metres, my objective was to get as fast as possible in the running position. A lot of people used to say I should stay down low as long as possible to go faster. I used to tell them to bend over and run and see how fast they can manage. If you have to run fast you have to get up and run. Simple,” said Lewis.

Simplicity became a complex, time-honed internal clock for Lewis when it came to long jumps, though it also involves sprinting, the dash is drastically different too.

“In the long jump, when I came out of the back, I would push and I would count my steps to make sure I was bang on rhythm, to the millisecond,” he explained. “The last thing I wanted while running down the runway were thoughts like, ‘oh my God, will I foul this one, or is my timing right?’ A few years back, when someone asked me about it, I counted the steps. I said one, two, three, four… till 21. I set the rhythm. It was always 21 and I would hit the take-off board at 21,” elaborated Lewis.

“When the interview came on TV, they played a 17-year-old video of me running in for a jump, and my steps matched my count. That’s how precise it used to be and that’s probably why I rarely fouled. I was always focused on perfection. In the long jump, the second you touch the board you have to take off in the correct angle with the correct movement. You only get about 1.1 seconds to do all that motion in the air. So you can’t think. It has to be totally reaction — learned response, trained response”

Also Read | The Walk: An Olympian, a Worker and a Home Yet to be Defined

The knowledge that there is a relentless and unforgiving process within the mindspace of the two champions makes us look at them a tad differently. The hard work humanises them, binding them with commoners. The process dehumanises them, binding them with computer algorithms.

However, the human elements trump the computer. They are bound by desires, fears, aspirations, childhood memories even.

“Many things go through your mind apart from the calculations, though,” Gebrselassie said. “When I was running in Berlin (world record attempt), my mind used to wander to the voices and the cheers of the spectators supporting me. Every now and then, my mind used to wander back to Ethiopia.”

Gebrselassie would think of Asella, the village where he was born, and where as a five-year-old he discovered running, as free-spirited as it could be. “I was born in the countryside,” he said. “By the age of five, I started going to school and it was far away from home. And to reach school in time for the morning sessions, I had to run the 10-km distance very fast. That’s how I began running…”

That’s how his runs were primed perfectly for the 10k, which earned him the two Olympic gold medals and multiple world titles.

Gebrselassie — with time on his side — had the luxury to be open to external clamour and cacophony. He lets memories flood in. Lewis, on the other hand, lived a reactive existence within an almost meditative trance. There were no memories of the past or childhood. That would come later, after the finish line.

Also Read | Olympics on Sail: Medal, Mettle and Mayhem in Munich

“When the time came for me to go to my mark, I can’t say I would go completely blank,” said Lewis. “I would clear my mind. The best way to describe it is like this. You and I are sitting here talking and very engaged. But if I wanted to hear him (pointing to one of his managers across the room) working with the book, I would go silent and listen for that sound. Let’s try it. We can’t really hear it at one go. But if we slow down and then listen for it… See, now you can hear the pages, hear him work on the phone. That’s what I used to do. I used to clear my mind. Then listen for the gun. I never tried to anticipate the shot. I knew the sound I wanted to hear and when I heard that I reacted. That’s why I reacted well and started well right through my career.”

In an ideal world we would aspire to be both — reactive and assertive like Lewis, contemplative and rich with hindsight like Gebrselassie. But in real life, we are either a sprinter or a marathoner. We can’t be both. This fact led to one point of disagreement I had with the Ethiopian legend while jousting over life and running.

“Running never fails us,” he had said. There was a pat on my back before he made the concluding statement with a bright smile writ wide across his leathred face.

“So, is it running or is it walking?” I asked.

“Running, my friend,” answered the two-time Olympic champion. “Running is the most universal form of physical exertion.”

My take was that running is but an extension of walking, and everyone walks. However, after saying that, I realised that I hardly walk or run anymore.

Seven years down the road, Gebrselassie’s words ring as I ponder on the point of the universality of the walk versus that of running. If only I could go out for a walk, and then run, pant without mask, and figure out, amidst lockdown, if it is indeed running over walking.

Of course, Gebrselassie knows the answer. Lewis too. Greatness, after all, is about reaching a point where you are aware of the answers to the questions you asked yourself when you embarked on the journey, when you began your run!

Read more sports stories from Newsclick

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.