Challenging the Unpopularity of Humanitarian Crises on Digital Platforms

Representational use only.

Right through the pandemic, we were told ‘nobody is safe until everyone is safe’, a pointed reference to the need for mass immunisation against the virus that causes the Covid-19 disease. However, judging from conversations on Twitter, the public has not got hooked to discussions about the biggest global race to inoculate the world. On digital platforms, public engagement with vaccines did not happen on an expected or necessary scale.

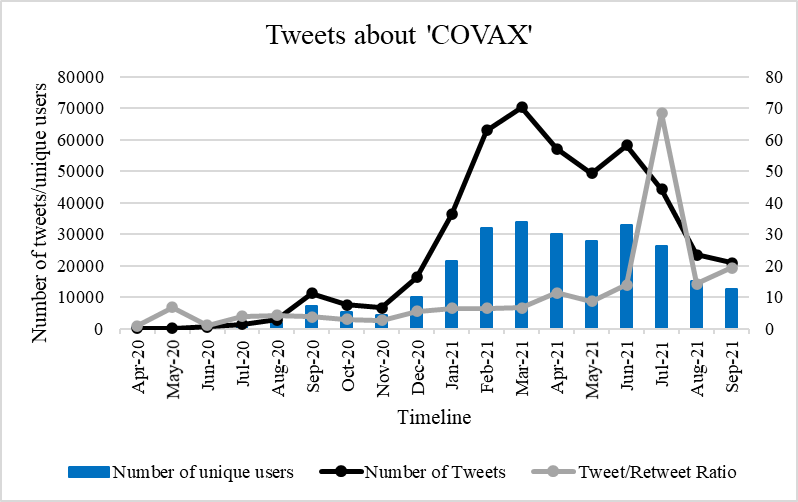

We know this because tweets that mention Covax or the Covid-19 Vaccines Global Access project—the global body that ostensibly took charge of supplying vaccines to those who need it most in 92 countries—have been declining since March 2021. These writers find that by the end of September, conversations about Covax were down to similar levels as in December 2020 (see chart 1). It is surprising considering the global heavyweights Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, and the World Health Organization lead the Covax initiative.

Chart 1: Tweets about COVAX

Online platforms are known to amplify on-ground chatter, but we learn from crunching data from Twitter that social media ignored the vaccine crisis. We can say that the fall in digital participation mirrors the on-ground performance of Covax, which is an estimated two years away from reaching its vaccination targets. However, there is more to it. Twitter data also indicates that most other global emergencies and humanitarian challenges likely suffer a similar fate as vaccination. Twitter can reflect ground realities, so the data on Covax potentially shows the low popular interest in other issues that concern the world. In fact, we already know that Covax is not the only major crisis that failed to gain traction on the Twitter platform.

Let us first look at the Covax numbers: In March, each user of the approximately 33.6 million unique users tweeted twice on Covax. After September, the frequency dropped to 1.6 tweets per user. So, not just the number of tweets, even the interest in tweeting has fallen. Though the number of new tweets has declined, there is an up-tick in retweets, akin to amplifying what others are saying. So, direct participation in conversations around Covax have fallen, but indirect or passive participation has considerably picked up and is trending upward. That said, the fall in direct digital involvement is worrying, given that millions of lives are at stake.

What puts the (un)popularity of Covax in perspective is the data on the volume of total conversations around it compared with other Twitter conversations. Over 18 months, the combined tweets and retweets around Covax add up to nearly 7.4 million. By comparison, the Korean pop theme #Sticker9thwin garnered 1.2 million tweets and retweets in just about six hours on just one day in October. Similarly, Thai TV show #Candyหวานจังหวานใจมิวกลัฟ got 1.3 million tweets and retweets in roughly the same amount of time on just one day, 3 October.

Even the most pressing emergency stood no ground online before these prevalent themes. We previously analysed tweets that mention the humanitarian crisis in Yemen and found that in 2017, only one Twitter user was speaking out for every 217 displaced persons in Yemen. By 2019, this dropped three-fold, to only one Twitter user for every 797 displaced persons. The crisis in Yemen could get just 0.67 million tweets and retweets over seven long years from June 2014 to March 2021. Topics such as football or daily state politics generate much larger volumes, often in just two months or a few weeks.

Dr Richard Hatchett, CEO of the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations, has noted the need for “aggressive action” to deter richer countries from hoarding vaccines, one key factor holding back the success of Covax. Unfortunately, the world did end up with a profound vaccine imbalance. However, it is also worth asking who has to take this “aggressive action”—is it the heads of state or the people? It is critical to note that the United Nations, of which the WHO is a part, is a global collective and not outside of the world. Put another way, if there is a lack of will to tackle the global vaccine emergency, it results from the lack of will of countries that must take action.

The data we have crunched does not show popular “aggressive action” to ensure the delivery of vaccines equitably, though it is one of the known goals of the Covax alliance. This lack of public action can reflect the absence of a will to demand accountability from heads of state on vaccination and other global emergencies. However, the onus does not rest only with the popular demand side. During most pressing emergencies, the supply of information gets constrained, which deters people from engaging with crucial issues, from the vaccine crisis to the devastation in Yemen.

With minimal reporting emerging from emergencies like Yemen on its crisis, it is natural conversations around it will be suppressed. Along with the states, the field agencies in conflict zones share the burden of making ground realities accessible to people across borders.

Take for instance Almigdad Mojalli, a contributor to The New Humanitarian (then IRIN) from Yemen, who was killed in an airstrike on his country. Mojalli had actively reported on the humanitarian catastrophe in Yemen, was in Jordan just before he died. There, to his surprise, he found that the war in Yemen rarely made the news. In an obituary on Mojalli published in The New Humanitarian, Adam Baron of the European Council on Foreign Relations was cited saying that the conflict in Yemen is “one of the most devastating” in the region, but one that “people apparently don’t get...”. Even data, as shown earlier, back the claim about this conflict going largely ignored beyond its borders. In early 2016, the GDELT Project found the online media coverage of Yemen was depressingly low: at below 5% in the Arabic press and under 1% of the news in all other languages. If this news barely trickled into Jordan, how confident can we be that it would be known or acknowledged beyond the region?

Sustained digital mass mobilisation is not easy due to the very nature of the digital world. Many a Twitter sensation is big but also short-lived, which makes it a highly competitive space. We see social media stars consolidate their fame only to make inroads into relatively conventional or steadier avenues. Digital marketing consultants and promotional campaigns have made it much more difficult for organic campaigns to sustain. That said, important conversations require continued efforts from people. Talking makes a difference—even digitally. At least, it acknowledges those affect and gives them hope. It sends the message that they are not forgotten. Technological advancements make talking easier, and if employed well, they can mobilise people to pressurise states to be accountable to their international commitments. But it will work without continuous conversations, and for those, there is no better time than now.

Vihang Jumle is a public policy student based in Berlin. Vignesh Karthik KR is a doctoral researcher at King’s India Institute, King’s College London. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.