Crossing International Borders: How Mobile is the South Asian Individual?

Image Courtesy: Ecija

The South Asian traveller, due to her nationality, gender, class, religion, etc. faces considerable restrictiveness in terms of international mobility. She is also often susceptible to being categorized as more ‘risky’ than others when seeking entry into a wealthy state of the global North. The recent visa restrictions imposed by the UK and the US on skilled workers from the global South need to be viewed in this light.

The populist governments of the global North view immigration from the global South as a threat to their security. They aim to make the legal entry of the people of the global South into the global North even more difficult than it already is. For instance, the Trump administration now requires more documentation from H1-B visa applicants. Before these changes, H1-B work visas were issued to young Indian techies for an initial period of three years, with high possibility of extension for another three years. The applicant now has to prove the duration of the project(s) allotted to her in her visa application. Based on this, the duration of the initial visa approval can be even less than three years now. The extension has been made difficult, hence making it next to impossible for Indian techies to be eligible for US green cards later. The UK also, despite shortages of labour in the healthcare sector, has increased the minimum wage cap for skilled non-European visa applicants. The UK’s visa restrictions have also impacted thousands of Indian techies migrating to the UK on short-term visas.

If the national citizenry is viewed as a community, then the border signifies the limits of that community. A passport and a visa grant temporary access to the members of various communities to the international space. Access to this international space though remains highly unequal for different individuals. What happens if we foreground mobility of people across borders in our evaluation of a region? This shifting of focus from states to borders creates a problem for the contemporary international system of Westphalian nation-states which conceptualizes populations in motion as security challenges to be managed.

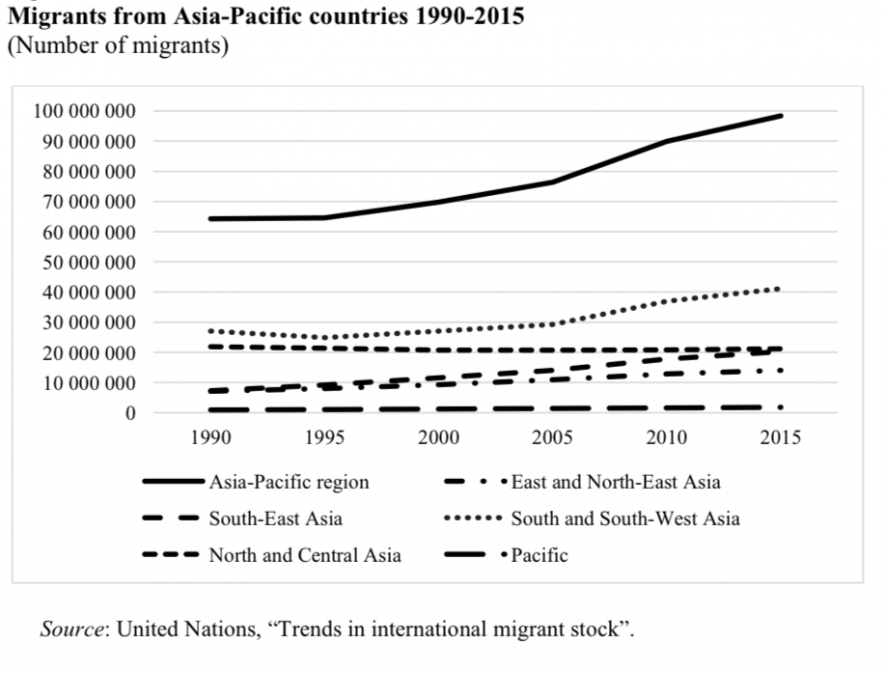

(Image Courtesy: UNESCAP)

South Asians qualify for very few visa waiver programmes internationally, and almost always have to obtain a proper visa before visiting a wealthy country of the global North. For example, nationals of all South Asian countries are required to be in possession of a valid visa when travelling to a Schengen member country. Additionally, nationals of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Pakistan and Sri Lanka require a visa to even transit through an airport located in a Schengen member state. The photograph and fingerprints of all visa applicants are collected at Schengen visa application centres, notwithstanding whether their visa applications are actually approved later or not. A South Asian visa applicant is mandated to attach the copies of her airline and lodging bookings, travel insurance and also bank statements along with the visa application, thus underscoring the implicit class-based discrimination of the visa policy. A short-term tourist visa is often the easiest to obtain when travelling to the Schengen area, compared to other visa categories like business visa, student visa, etc., again highlighting how the wealthy states of the global North prefer to selectively open their borders to those South Asian applicants who can prove that they have enough money in the bank.

Among South Asian countries, India, ranked at 72 by Passport Index, has the greatest international mobility with visa-free access to 54 countries. This is followed by Bhutan with visa-free access to 51 countries, ranked internationally at 75. Myanmar is ranked at 82, with visa-free access to 42 countries. Sri Lanka is ranked at 85, with a visa-free access to 38 countries. Bangladesh and Nepal are both ranked at 86, with a similar visa-free access to 37 countries each. Pakistan and Afghanistan are ranked at 89 and 90 respectively. They have the globally lowest visa-free access to 28 and 24 countries respectively.

According to the UN World Tourism Organization’s Visa Openness Report, the average global mobility score in 2015 was 89; this score indicates the extent to which citizens are affected by visa policies. This score can range from 0-215. While the advanced economies’ score was 154, India’s score was 50. Since other South Asian countries enjoy even lesser international mobility than India, their score, if calculated, is bound to be lower. In contrast, according to the International Organization for Migration, South Asia also has the world’s second highest number of adults planning to migrate, with the number standing at a staggering 9.8 million persons.

What does this tell us about the contemporary international mobility regime? To answer this question, some context of the development of modern migration control is needed first. During the colonial era, regulations surrounding international migration were established in order to encourage certain kinds of movement while hampering other kinds. It was during the 1880s that newer migration controls were framed that were aimed at excluding the global South from the wealth and the privileges of the global North. The adoption of these migration rules by states of Asia was possibly guided less by practical needs, and more by the urgency to live up to the international ideal of a well-governed nation-state.

In the present international mobility regime, all travellers are categorized along a spectrum of risk based on the biometric attributes of their bodies like fingerprints and iris scans, and sociological attributes like residence, nationality, race, religion, etc. People now even have “data-doubles” – virtual identities stored in networked databases – that have much greater mobility than what those people have in their actual lives; the travels of one are bound to affect those of the other. This all the more so if one is locally defined as an “other.” The contemporary form of traveller risk profiling marks a significant shift in the discourse on international mobility since it represents a lack of precise information on the specific traveller, and the existence of mere suspicion based on statistics, sociology or even stereotypes. This breeds a cycle of insecurity resulting in greater surveillance of the general mobile population.

Samah Rafiq is a PhD research scholar at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are the author's personal views, and do not necessarily represent the views of Newsclick.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.