Educational Equity: Is Fundraising the Answer to Caste-Oppressed Students?

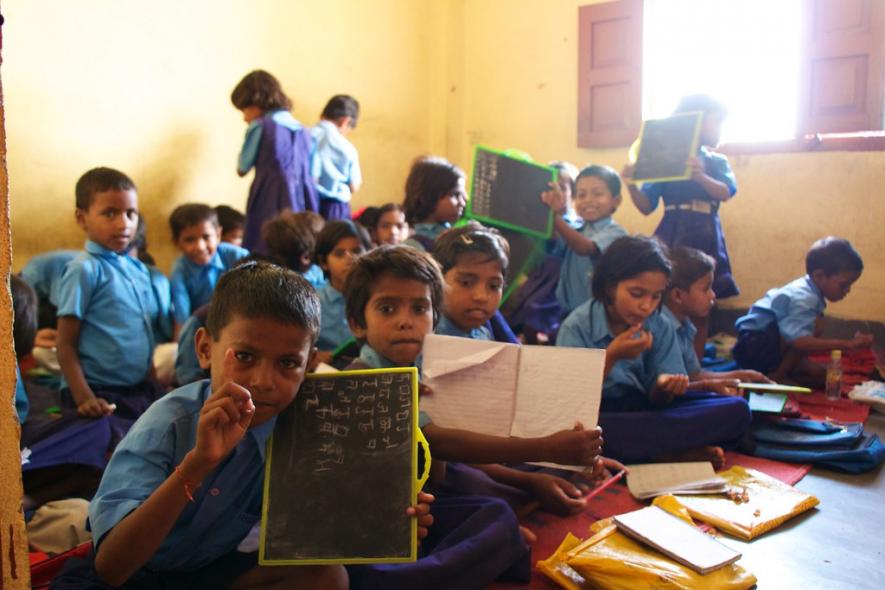

Representational Image. Image Courtesy: Flickr

In recent years, there has been a notable surge in fundraising initiatives and requests in different social media networks -- especially with increasing numbers of different crowdfunding platforms during and after the COVID-19 pandemic - often soliciting financial support for health-related causes, assistance in conflict-affected regions, natural disasters, and other socio-economic causes in different communities.

More recently, there has been a growing trend in fundraising efforts directed toward support in pursuing higher education, particularly in India. Students are initiating campaigns for studies abroad and Bachelor, Masters courses in engineering, medicine, etc., even in reputed national institutions and universities, such as IITs (Indian Institutes of Technology). Most of these students hail from the historically oppressed caste communities. This article aims not to criticise students engaged in fundraising but to explore how systematic factors contribute to making students vulnerable and desperate to seek funds for their higher education.

As per the T.I.M.E Association’s 2021 report on International Student Mobility, India comes second after China for outgoing student mobility to foreign universities, with an increase in student numbers by 100% in the decade between 2008 and 2018. To the bare eye, the continuous rise in the number of students joining foreign universities appears to be in a positive light.

Still, it is important to look into students from which socio-economic backgrounds are going to foreign universities. Undoubtedly, it is mostly students belonging to enabling financial backgrounds of dominant caste communities who can afford to study abroad. Only a countable number of students from caste-oppressed marginalised communities are able to join these top-ranked universities.

Many of these students are first-generation learners who often come from the rural parts of India with limited or no socio-economic capital, hardly having opportunities to fund their higher education themselves. It is mostly through some scholarship schemes like the National Overseas Scholarship (NOS) for the Dalit-Bahujan-Adivasi or Scheduled Caste (SC)-Scheduled Tribes (ST)-Other Backward Castes (OBC) students, which can support their higher studies abroad. However, over the years, it has been evident that these schemes have been poorly implemented and have hardly sent a considerable number of students, as intended during their inception.

Different scholarships from foreign universities cater to applicants from across the globe, along with some scholarships, particularly for students from India. While none of those scholarships distinctively mention the inclusion of students coming from marginalised communities, even if they apply, their scope of receiving these scholarships is very slim. Coming from an environment providing sound and standard education, thus enabling high cognitive skills, the aforementioned scholarships are bagged mostly by caste-privileged students.

Growing up amid years of socio-political marginalisation, when even accessing basic education does not come easily for SC-ST students, having the initial orientation to the different complex application procedures to these general scholarships, like preparing a fluid statement of purpose, registering and appearing for different linguistic tests of IELTS, TOFEL, GRE etc. throw them into unfair competition with all other non-caste-oppressed students.

However, in recent years, amid the emerging discourse around the absolute necessity of affirmative actions like dedicated scholarships for historical caste oppressed and other marginalised learners in India, some prominent foreign universities have developed schemes distinctively for SC-ST students. For example, The Oxford India Centre for Sustainable Development (OICSD) at Somerville College of Oxford University invited applications for the Savitribai Phule Scholarship earlier this year to award to one first-generation learners from the Dalit, Bahujan and Adivasi (SC/ST/OBC) communities which aims to gradually increase the award number to three. But as per their website, they are yet to have the estimated cost of 200,000 GBP and are appealing for grants/donations to raise the required funds to award three scholarships!

Again, since 2022, the Center for Modern Indian Studies (CeMIS) at the University of Göttingen has been awarding two scholarships, one each for Master’s and Doctoral level, to applicants fulfilling the criteria of coming from at least one of the following backgrounds; Dalit or Adivasi; Children of informal sector labourers; Religious Minorities; First-generation learners. While these initiatives are commendable, there's a concern that the eligibility criteria for these scholarships don't fully account for the unique challenges various marginalised groups face.

Each community, whether it's SC, ST, OBC, religious minorities, or others, has its own set of socio-political marginalisation experiences. Therefore, students from each of these communities would require financial support to pursue higher education abroad. Despite the hosts of these scholarship programmes being Indian Studies Centres, with scholars having extensive research expertise on different aspects of historical marginalisation in South Asia, in the real essence of leading policy-driven actions, they fail to understand the various intersectionalities among the communities. With the tendency to group these communities together, these schemes ultimately focus on public promotion of ‘diversity and inclusion’ in their respective organisations regardless of the impact on the communities designated for the scholarships.

This brings us back to the conversation of fundraising, as, in the absence of enough funds and a number of financial support schemes for the Dalit-Bahujan-Adivasi (DBA) students both within India and abroad, they have no choice but to try to crowdfund their higher educational expenses. But easier said than done, raising funds from crowdfunding is a very emotionally taxing process which is highly likely to exacerbate the already existing generational trauma of marginalisation in the individual seeking to fundraise.

Crowdfunding relies on reaching a wider audience, often through online means of social media platforms. These require a big social network following as well as personal connections with a considerable visual presence online, which ideally should be convincing to potential donors.

However, these networks come with the added privilege of having pre-existing social capital, which students from DBA merely have. For example, these crowdfunding options are more likely to work for the dominant caste students, as they have networks and connections in their family and friends coming from similar caste locations, mobilising their fundraising capacity.

Most of the individuals who have been forced to live on the margins of society might not have a big social and personal connection along with financial affordability for utilising compelling means for promotion of their campaign promotion means to create a wider appeal and engage with potential donors who are again often looking for trusted sources to donate amid so many existing fundraising initiatives for different purposes. And even if they manage to raise funds, they often feel a strong sense of accountability, sometimes even to anonymous donors. This process further reinforces the internalised stigma of being the 'other’ identity in the DBA students.

Hence, going for crowdfunding may work for a few students from the oppressed caste but not for most. While these few successful fundraising initiatives benefit those few individuals, it is broadly fuelling a generalised discourse that all the caste-oppressed DBA students have the privilege or necessary financial support to go abroad for higher studies.

This only legitimises the government’s and the educational institutions' inaction in creating more financial assistance schemes for caste-oppressed students. In the absence of such support, the marginalised students may try to turn to bank loans for education, which is again not feasible in the lack of possessing any tangible wealth as collateral. Ultimately, it pushes the students to seek crowdfunding. Thus, the caste-oppressed students keep on spinning in the detrimental wheel of socio-economic distress while trying to break out of marginality through upward mobility through higher education.

Universities like Oxford, which have a global reach and influence, often celebrate their leadership in academia and generate significant discourse about India. Situated in the former colonial heart of the subcontinent, these institutions hold a unique position of power, privilege, and funds. So, as they celebrate their status, the question arises, “Why should scholarship initiatives for historically oppressed communities, such as the SC-ST students, rely on fundraising efforts?”.

Also, it is a responsibility that arguably falls on the shoulders of the Union Government of India. As a country positioning itself as one of the top three emerging economies globally, it is not an insurmountable task but rather an inherent duty for the government to allocate resources for the higher education of marginalised students.

Unfortunately, this responsibility has been consistently neglected, as even the existing scholarship programs have suffered from under-implementation for years. Hypothetically, a modest investment of Rs 500 crore, averaging just Rs 1 crore per student for SC, ST, and BC communities annually, could send 500 students overseas for higher education.

In this era, when institutions believe that they are championing inclusive social justice, it is the government's and universities' moral and social responsibility to establish scholarship initiatives that address historical oppression. Failing to do so would only keep adding to the ongoing perpetuation of understanding India's diverse socio-cultural everyday realities through the privileges of dominant Brahminical discourse while silencing the marginalised voices that tell the stories of India's subcontinent and its deep history of multiple aspects of marginalisation.

The writer is a postgraduate scholar from Telangana, India, and was formerly a Government of India National Overseas Scholarship Fellow at the International Institute of Social Studies, The Hague. He currently works as a Senior Researcher for the National Campaign on Dalit Human Rights (NCDHR) in New Delhi. Views expressed are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.