India’s Terrible Track Record in Unemployment Benefits

Unemployment is a persistent issue in India and a topic that has always captured the media’s attention, even before the COVID-19 pandemic. During 2017-18, open unemployment rose to a historic 6.1% high which have declined slightly in 2018-19, to 5.8%.

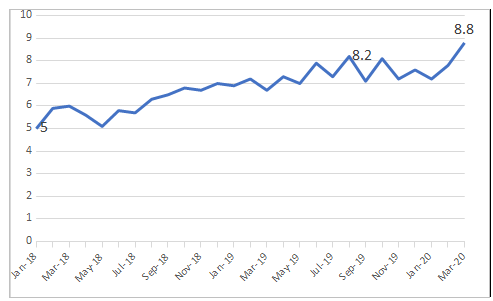

However, the high frequency unemployment rates put out by the Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy (CMIE) showed higher and rising unemployment through last year (2018-19) which contradicts the rather comforting picture shown by government data. The unemployment rate, in fact, spiked to the highest level, 8.8%, in February 2020 (See Figure 1)

Figure 1: Monthly unemployment rates (%) Jan 2018-Mar 2020

Source: CMIE, 31 August 2020.

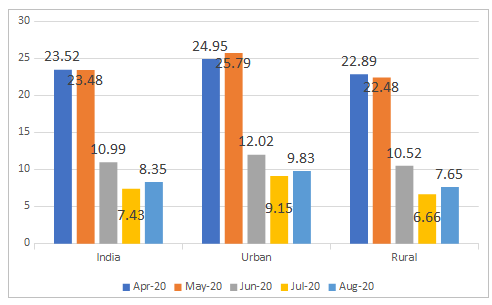

Then the COVID-19 pandemic hit India, and during April-May, unemployment shot through the roof and peaked at around 24% in urban and rural segments. This was during the strict national and regional lockdown. As economic activity picked up gradually, unemployment rates declined substantially, but even in August, they were stubbornly higher than the pre-coronavirus levels, at 8.35% (See Figure 2).

Figure 2: Unemployment in India during COVID-19 months, Apr-Aug 2020

Source: CMIE, 1 September 2020.

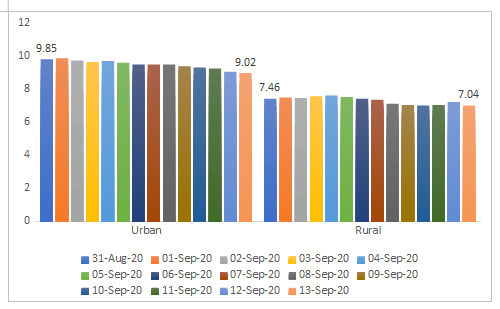

This month, the urban and rural unemployment rates remain stubbornly resistant to change (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Urban & rural unemployment rates, recent days in India

Source: CMIE, September 2020.

Several micro-level studies have reported severely high unemployment, along with lower intensity of working hours, higher incidence of non-wage payment and fewer cases of partial wage payment. These imply greater loss of savings during most of the lockdown. CMIE data also shows informal employment growing and salaried jobs dropping substantially, by 18.9 million, during the COVID-19 period. Informal workers, especially migrants, have borne the brunt of the adverse effects of COVID-19. Already vulnerable, their economic capacity was worsened by the high retail inflation of 6.09% in June, which topped 6.93% in July.

Given the magnitude of their sufferings, and considering the pandemic is still raging, an unemployment allowance or cash assistance would have provided respite to India’s workers. Economists and all trade unions have demanded universal or targeted cash transfers for three to six months. However, the Centre did not implement this, inviting criticism for the inadequacies of relief measures announced by the government. There are a number of laws safeguarding the unorganised workers: The Inter-State Migrant Workmen Act, 1979 (ISMWA), the Unorganized Workers’ Social Security Act, 2008 (USSWA), the Building and Other Construction Workers Act (BOCWA) and its supplementary law of BOCW Cess Act, 1996 and these have not been implemented at all – hence it has been a double whammy for workers.

The proposed Social Security Code (SSC), 2019, does not provide for unemployment benefits, though this benefit does figure in its definition of social security benefit. While the states and central governments’ responded to the migrant crisis with encouraging words, they remained symbolic. The Supreme Court had to pull up Maharashtra and Delhi for not filing affidavits on implementation of laws concerning migrant workers.

Unemployment insurance/benefits in India

In 2002, the Second National Commission on Labour (SNCL) recommended an unemployment scheme contributed to by workers, employers and the government, run by the EPFO, and applicable to establishments and workers covered by EPFO. The Centre, however, introduced in April 2005 a narrowly-conceived unemployment insurance scheme instead; under the Employees’ State Insurance Act, 1948 (ESI Act), which it called Rajiv Gandhi Shramik Kalyan Yojana (RGSKY).

RGSKY provides unemployment allowances to already insured persons who lose their jobs due to retrenchment, closure or permanent (at least 40%) disablement arising out of non-employment injury. The original scheme was changed over the years, for instance in 2009 and 2016, to become simpler and extend more benefits. There are three basic conditions to avail unemployment allowance: workers in the establishment/factory must be covered by the ESI Act, which is applicable to non-seasonal power-using factories with 10 or more employees (20 in Maharashtra), and shops, hotels, restaurants, cinemas including preview theatres, road motor transport undertakings and newspaper establishments with 10 or more employees.

Two, “workers” are defined in the ESI Act as those who draw wages below a prescribed threshold which keeps changing. For example, with effect from 1 January 2017, the wage threshold was raised from ₹15,000 to ₹21,000.

Three, at the time of losing employment, workers (below 60 years old) must be insured and have been insured for a specified tenure, which was reduced from five to two years. Losing a job due to strike, voluntary retirement, dismissal due to indiscipline, among others, disentitles a worker to this benefit, but the eligible workers can avail an allowance equal to 50% of their last average daily wages for the first 12 months and 25% of the last average daily wages for the remaining 12 months. The allowance can be taken in parts, but the cap is 24 months’ wages.

Considering the transformation of jobs from long-term to short-term, the government introduced the pilot Atal Beemit Vyakti Kalyan Yojana (ABVKY) for two years from July 2018, expecting to benefit over 1 million workers. It provides 90 days of allowance for except if the job was lost due to misconduct or voluntary retirement—and only once in a lifetime. The allowance is 25% of the average per-day earning during the previous four contribution periods. The claimants should have been in insurable employment for two years, and they must have contributed for at least 78 days during the four contribution periods. (A contribution period is six months: April to September and October to March.) Their Aadhaar and bank account should be linked with the insured person database, and so on.

Shortcomings of ESIC unemployment schemes

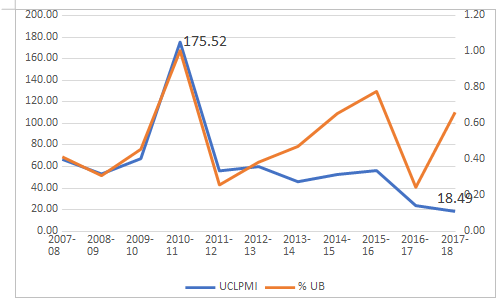

One of several obvious shortcomings is that they are narrowly restricted in terms of their applicability. The determining factor is the ESI Act, its coverage of establishments and workers and that the beneficiaries are insured persons who have contributed. The Parliamentary Standing Committee on Labour (PSC) observed, “...one of the primary causes for low ESIC coverage has been tardy enforcement mechanism.” Two, as trade unions have complained, employers refuse to provide certificates of closure as they do not want to settle other dues, such as gratuity. Three, the dissemination of these schemes is quite limited. The numbers in Figure 4 show the poor performance of RGSKY.

Figure 4: Beneficiaries under RGSKY, 2007-2017

Note: UCLPMI is the number of unemployment claims per million insured persons (%). UB refers to the proportion of unemployment claims’ expenses in total cash benefits.

Source: Annual Reports under ESI.

Between 2007 and 2017, only 10,728 unemployment claims were made: an average 975 claims a year. This is very poor off-take considering that on average 17.63 million insured persons were on the record during this period. The highest number of claims was around 2,510, made in 2010-11. So, unemployment claims on average were at 0.51%, which climbed to 1.01% on account of high off-take in 2010-11.

Unemployed workers on average got ₹36,046, though with inflation in wages during 2016-18, the average annual claim amount rose to around ₹72,000.

Social Security Code, 2019, and unemployment benefits

Section [2(70)] of the SSC 2019, includes unemployment benefits, access to healthcare and income security, particularly in old age, unemployment, sickness, invalidity, work injury, maternity or loss of a breadwinner as part of social security. However, it has no provision relating to unemployment benefits. An earlier draft from 2018 did refer to an allowance “in case of loss of job or earning due to lay-off, retrenchment or any other eventuality specified in the scheme”.

But the 2019 draft substantially waters down both the 2017 and 2018 drafts. Other than dropping the unemployment benefit provision, it virtually reproduced the existing laws that it seeks to consolidate. The PSC observed that despite wider coverage of ESI Act compared with the EPF Act, the total number of employees covered was half in the case of the ESI.

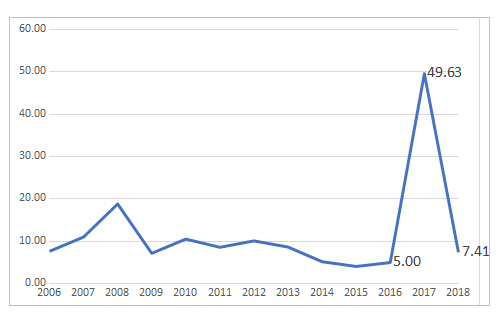

Figure 5: Year-on-year growth of insured persons under ESI scheme, 2007-18

Source: CMIE, September 2020.

The 2017-18 spike was most probably due to the wage threshold for workers going from ₹15,000 to ₹21,000. The annual average growth rate for 2006-18 was 11.84%, and excluding the outlier growth rate, it was 8.69%. ESIC’s Vision 2022 proposes that by that year, the ESI Scheme will cover all districts and 100 million workers. When the parliamentary committee asked the government why it had excluded unemployment allowance, though the second national commission on labour recommended it, the government claimed that the coverage of ESIC is less as the scheme “does not operate at an all-India level”. It also said that through the Social Security Code, ESIC will extend coverage from 3.49 crore to 10 crore families, or around 30 crore beneficiaries.

But the Social Security Code has retained the existing establishment threshold. Further, the government argued before the parliamentary committee that unemployment allowance is already provided for under the ESI Act. “For the unorganised workers, basic social security has been taken care of in the proposed code,” it said. In fact, the government went ahead and said that the Code largely complies with the ILO’s Social Security Convention, 102 of 1952 (not ratified by India.)

Despite extremely limited coverage of unemployment schemes and a history of poor off-take of claims, the government still proposes to stick to the existing legal framework. The PSC’s responses to the government’s position are striking: “As the hitherto low coverage of ESIC speaks volumes of the lacunae existing earlier, the Committee impress upon the Ministry to ensure that substantial improvements are built in the Code to enhance coverage as envisaged within a stipulated timeline. The Committee, simultaneously, desire that the apparent restriction that is being caused due to the ‘threshold’ stipulations for ESIC coverage be also looked into holistically with a view to ensure universal coverage of ESIC benefits.”

Chapter IX of the SSC, which deals with social security for unorganised workers, virtually reproduces the existing USSWA, 2008, save for a “cautious” provision that says a social security fund “may” be constituted by the central government. “Shall” would have made such a fund compulsory. Instead, the government has left the matter in the hands of the executive, to revise or revisit from time to time, offering nothing concrete by law.

Given the fiscal and growth shocks due to COVID-19, a government driven by fiscal conservatism is hardly expected to devise an adequate social security scheme at this moment. However, it does not seem to have referred to the available literature on social security and other concerns of informal workers, studied in great detail by the National Commission on Enterprises in the Unorganized Sector, NCEUS, 2004-09. None of the Codes framed by the present government feature the NCEUS’ findings, though the second national labour commission, 2002, which had been appointed by a previous BJP-led dispensation (1999-2004), is often referred to. The NCEUS had advocated a contributory insurance model and estimated that a national minimum social security covering health, maternity, life insurance, old age security and so on would cost a paltry 0.48% of GDP. Fact is, fiscal conservatism typical of neo-liberalism is why the NCEUS report has languished. Even the UPA government which commissioned the study did not implement it.

The present government’s approach to social security is ad hoc. Popular but largely unsuccessful schemes are announced now and then—the Pradhan Mantri Shram Yogi Maan-dhan was introduced in February 2019, Atal Pension Yojana came in May 2015 replacing the Swavalamban Scheme; then came a scheme for accidental death and full-debility risk, the Pradhan-Mantri-Suraksha-Bima-Yojana. A national health insurance scheme, Rashtriya Swasthya Bima Yojana or RSBY, which is now known as PMJAY was launched and after this came Ayushman Bharat and others.

Oxfam’s Ravi Srivastava estimates that all kinds of social security schemes run by the government accounted for less than 1% of the total budget expenditure and less than 0.10% of GDP from 2012-13 to 2018-19.

COVID-19 and unemployment benefits and reliefs

The ESIC has extended the ABVKY till 30 June 2021 and relaxed the conditions and relief amount for 24 March to 31 December. Relief has been raised from 25% to 50% of average wages payable for up to 90 days of unemployment and will become payable after 30 instead of 90 days. Unemployment allowance can be claimed directly rather than through employers as earlier, and is credited to bank accounts. The insured should still have been in insurable employment for at least two years before unemployment and must have contributed for 78 days in the contribution period immediately preceding unemployment. There are a number of other such conditions that apply. These, however, are fire-fighting measures, and we do not know how “popular” they are.

State governments did provide cash assistance to workers eligible for the unutilised funds collected under the BOCW Cess Act, 1996. Yet, only 16% of the ₹31,000 crore unused fund was disbursed. A few including Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand were not disbursing this money even by 23 June, well into the pandemic crisis phase. In any case, this amounts to depriving assistance prescribed by BOCWA, and offering relief from a fund that workers are already entitled—not the state using its own funds. Similarly, while some states such as Uttar Pradesh made ad hoc cash transfers of ₹1,000 to migrant workers, overall, India stared at utter non-implementation of the ISMWA amidst lack of a primary database—a list identifying workers.

Finally, it fell on the much-maligned MNREGA to provide the sole universal “rural” employment. It was accessed aggressively from May onwards. And, unemployment, as we know, has declined primarily in rural areas (and to some extent in urban areas) due to the huge uptick in MNREGA. So much so that it was not just academics but even chief ministers who started demanded an urban MNREGA-like scheme.

Despite decades of high unemployment and under-employment, the Centre created a scheme for unemployment allowance only in 2005, and it has a poor track record. The State has placed the entire burden of unemployment on workers and employers. It is workers who will bear the brunt of unemployment. The legal compensation under IDA is a pittance and disputes on retrenchment or closure comes with litigation costs. COVID-19 has demonstrated that legal coverage is no guarantee in any case. Around 70% of regularly employed workers in the non-agricultural sector do not get written job contracts. Around 50% are ineligible for any social security according to the Periodic Force Labour Force Survey, 2017-18. Employers are unlikely to provide them a VRS or ESS.

At any rate, employment is the only cure for unemployment. However, excluding more and more industrial establishments from the purview of the IDA is not a “reform” as it will intensify the precariousness of workers. Changing thresholds under the Factories Act or Contract Labour Act or fixed-term employment are not silver bullets either. India urgently needs a universal and comprehensive social security scheme and not disparate schemes, and knee-jerk responses (in terms of ad-hoc payments). Poor implementation and fiscal conservatism, while pushing labour “flexibility” and cutting contributions to social security further cause loss of welfare of informal workers. Lawmakers must realise equity and efficiency are twins and dismantling one and pursuing the other will be counterproductive as shown by the development record here as well as globally.

The author teaches human resource management at XLRI, Jamshedpur. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.