Kashmir’s History Shows Nehru-Patel Binary Exists Only in Sangh Imagination

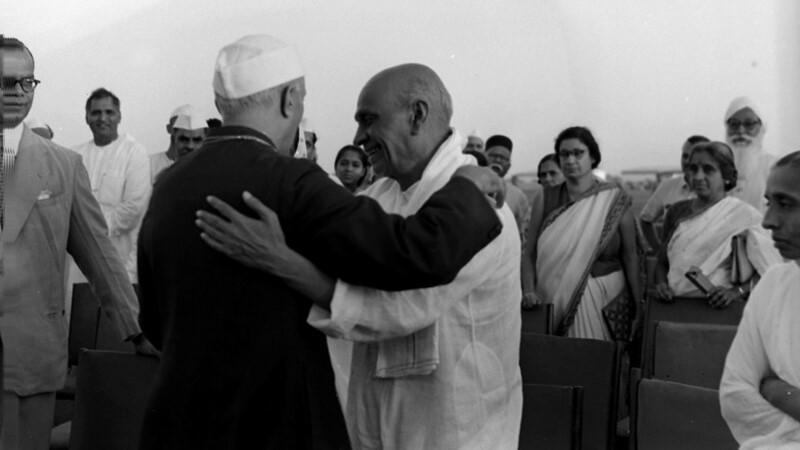

Jawahar Lal Nehru and Sardar Patel. | Image courtesy: flickr

The just-concluded Bharat Jodo Yatra, which ended in Kashmir, got an overwhelming response from people in the Valley. But that did not deter some commentators from using the occasion to indulge in Nehru-bashing, blaming the first prime minister for the region’s political imbroglio. Some used it to advance the binary between Nehru and Sardar Patel yet again, which hinges on the notion that if independent India’s first home minister and deputy prime minister had handled the Kashmir issue, it would have been resolved. This understanding is not only naïve and accusatory but also far from the truth. All it does is serve the Bharatiya Janata Party-Rashtriya Swayam Sevak’s narrative on the troubled past and painful present of Jammu and Kashmir.

On the eve of India’s independence from British colonial rule, the princely states were given the option to merge with India or Pakistan or remain independent. Most princely states merged with newly-formed India with relative ease. The problem, however, erupted when it came to the Hyderabad and Kashmir princely states. The Indian State undertook police action, nicknamed Operation Polo, to merge Hyderabad with itself. The merger of Jammu and Kashmir was more complicated, partly due to its geographical proximity to Pakistan and the fact that most of its population was Muslim.

The ruler of Kashmir, Maharaja Hari Singh, sought an independent Jammu and Kashmir. He offered a so-called standstill agreement, which meant there would be a political status quo while it would have access to the facilities of India and Pakistan. Pakistan accepted this, and its flag flew over post offices in Kashmir, as it was running the regional postal system. India did not accept this agreement, mainly because of a third crucial factor: Nearly two lakh Muslim residents of the State were massacred in Jammu, widening the communal divide and changing the region’s demographics from Muslim to Hindu-majority. This widespread violence is what partly triggered the Kashmir crisis. Commentator and film-maker Saaed Naqvi wrote, citing a 10 August 1948 report published in The Times, London, about the killings in Jammu, that ‘2,37,000 Muslims were systematically exterminated—unless they escaped to Pakistan along the border—by the forces of the Dogra State headed by the maharaja in person and aided by Hindus and Sikhs. This happened in October 1947, five days before the Pathan invasion and nine days before the maharaja’s accession to India’.

With the violence as their pretext, tribals supported by the Pakistan Army launched an attack on Jammu and Kashmir five days later. The State was unprepared to face the assault and wanted India to send the Army to quell the aggression. Against this backdrop, the maharaja signed the treaty of accession to India, though earlier, he had refused to merge with India. Also, MA Jinnah, Pakistan’s founder, had commented that Kashmir is a cheque in his pocket he could encash at will. The National Conference, then known as the Muslim Conference, led by Sheikh Abdullah, had launched a democratic agitation against the maharaja’s rule and an end to the feudal social structure. Three key states (including Junagadh, a Hindu-majority princely state led by a Muslim ruler) were unwilling to merge with India. Of these, historical records show Patel was willing to let Kashmir go to Pakistan—provided Junagadh and Hyderabad merged with India.

Historian Rajmohan Gandhi writes in his book Patel: A Life that Patel was thinking of striking an ideal bargain. If Jinnah let India have Junagadh and Hyderabad, he would not object to Kashmir acceding to Pakistan. Gandhi cites a speech Patel delivered at the Bahauddin College in Junagadh following the latter’s merger with India. In it, he said, “We would agree to Kashmir if they agreed to Hyderabad.”

Remember that in Kashmir, unlike other princely states, Pakistan was also involved and proximate. That is why Nehru, holding the foreign affairs portfolio too, had to take the lead in the issue. But Patel and Nehru were on the same page in this endeavour—and Patel was keener on Junagadh and Hyderabad than Kashmir. The negotiations over Article 370 were also taking place when Patel was home minister.

The historian Srinath Raghavan said in a wide-ranging lecture on “Kashmir: The State and The Status” that Patel was home minister when Article 370 was introduced and central to its deliberations. While other experts may argue over his centrality in drafting the article, there is agreement that he was aware of the deliberations, and there is no evidence he opposed it. Besides, others have argued that the present government-led argument that Patel would have fared better than Nehru on the Kashmir question is not backed by evidence. Legal expert Arghya Sengupta wrote, analysing Raghavan’s lecture, that “Patel was neither central to Article 370 as Raghavan suggests, nor is there any evidence that his centrality would have ensured full integration of Kashmir with India, as is assumed by the governmental narrative today”.

Those who suggest Patel would not have called for a ceasefire should know that according to Sardar Patel’s Correspondence, 1945-50, published in 1974 by the Navjivan Publishing House, Ahmedabad, he expressed quite the contrary sentiment. He said on 4 June 1948, in a letter to Gopalswamy Ayyangar, the ‘military position is not too good, and I am afraid that our military resources are strained to the utmost’.

The march of the Indian Army did save Kashmir from the marauding tribals supported by the Pakistan Army, but the ceasefire was declared to protect civilians and ensure a peaceful resolution through the United Nations. Taking the issue to the UN is also criticised, but that must have been the best option in those circumstances, and Patel greatly approved it. “As regards specific issues raised by Pakistan, as you have pointed out, the question of Kashmir is before the Security Council,” he wrote in a letter to Nehru dated 23 February 1950. He continues, “Having invoked a forum to the settlement of disputes open to both India and Pakistan, as members of the United Nations Organisation, nothing further need be done in the way of settlement of disputes than to leave matters to be adjusted through that forum.” The letter is available in the tenth volume of the same book.

Attempts to create a binary between Nehru’s position and the probable position of Patel are motivated by political considerations. Both leaders were on the same page on the Kashmir issue. And if the people of Kashmir have welcomed the Bharat Jodo Yatra, it is simply a signal and an opportunity to introspect and restore democratic norms in the erstwhile State.

The author is a human rights activist and taught at IIT Bombay. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.