Learning from History: Renegotiating the India Nepal Treaty

According to the reports, the India Nepal Treaty of Peace and Friendship signed in 1950 could be revised. This flows from a recommendation of the Eminent Persons' Group (EPG) set up jointly by the two countries to review their bilateral relations. Though the report of the EPG has not been made public, certain key elements may be inferred from what is stated in news reports. Two of the gleaming points are: Nepal wants to remove Article 2 of the existing treaty, as well as, regulate the Indian citizens residing and carrying out commercial activities in Nepal. There are voices within Nepal who want the treaty revised and brought in line with a 21st century-world. If the treaty is indeed revised, it would not be the first time India will have a treaty with a Himalayan neighbour revised. In 2007, the 1949 India Bhutan Treaty of Friendship was revised. In this respect, it may be worthwhile to look at treaties India had signed with its Himalayan neighbours, as well as, to look at the differences in the terms between the 1949 and 2007 treaties with Bhutan.

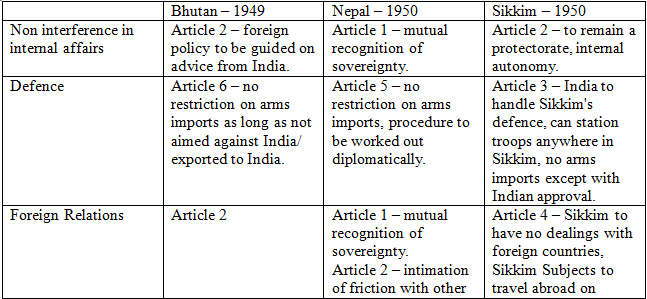

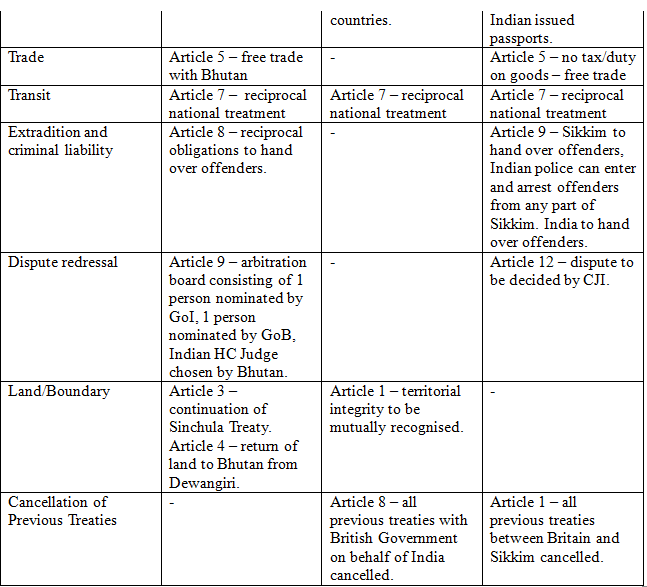

Between 1949 and 1950, India had signed three treaties with its Himalayan neighbours. The first being with Bhutan in August 1949, then with Nepal in July 1950, and lastly with Sikkim in December 1950. Though the first two treaties established relatively sovereign relations between the parties, the treaty with Sikkim maintained the status quo that prevailed during the British Raj. In the case of Bhutan, the treaty did not have a clause cancelling all previous treaties, whereas the treaties with Nepal and Sikkim did contain such a clause. In terms of arms imports and defence, the treaties with Bhutan and Nepal did not place any restrictions other than one: imported arms were not to be used against India's interests. In the case of Sikkim, prior approval to import arms was mandated. Also, India would take over Sikkim's external defence. Nepal was recognised as a sovereign entity, whereas Bhutan's foreign policy would rely on the advice of India. Sikkim, on the other hand, was barred from having any foreign relations.

In terms of trade and transit, the treaties provided for reciprocal national treatment. The treaty with Nepal did not contain a clause for dispute resolution. The treaty with Bhutan provided for an arbitration panel consisting of three members. Bhutan and India would nominate one member each, and the third member would be a Judge of an Indian High Court chosen by Bhutan to head the panel. In the case of Sikkim, disputes would be decided by the Chief Justice of India, whose decision would be final.

An interesting aspect of the three treaties concerns who signed them on behalf of the parties. The 1949 treaty with Bhutan was signed by the Political Officer in Sikkim on behalf of India, whereas it was signed by representatives of the Bhutanese King for Bhutan. The 1950 treaty with Nepal was signed by the Indian ambassador on India's behalf, and the head of the Rana regime for Nepal. The Sikkim treaty however, was signed by the Political Officer in Sikkim and the Chogyal of Sikkim. Thus, for Bhutan, bureaucrats signed on behalf of India, whereas for Nepal and Sikkim, it was either the Head of State or the Head of Government. At the time, this may not have raised too many eyebrows, considering that during the colonial rule, this was the norm in India.

The 2007 treaty with Bhutan saw a shift in India's position. The major change being that under the new treaty, disputes would be resolved through bilateral negotiation, rather than arbitration by a panel headed by an Indian High Court Judge. The other important change was that Bhutan now no longer needs to carry out its foreign policy on the 'advice' of India. Though these important changes were made (the new treaty no longer resembled a colonial treaty), it has been argued that India still retains a choke-hold on Bhutan's internal affairs. One example of this was when India decided to unilaterally suspend subsidies on gas and kerosene before the Bhutanese general elections in 2013. The then ruling party – Druk Phuensom Tshogpa (DPT) – led by the Prime Minister Jigme Yoezar Thinley had sought to establish diplomatic ties with China. The subsequent suspension of subsidies were perceived in Bhutan as India punishing the country for adopting an independent foreign policy. Whether this was really the case or not, the damage had been done. Suspicion in the minds of the Bhutanese have existed since India's actions in Sikkim in the 1970s. Despite the outrage, the DPT lost the elections and the Peoples' Democratic Party (PDP) headed by Tshering Tobgay took its place. The PDP is regarded as more sympathetic to Indian geopolitical concerns.

Nepal, like Bhutan, is no stranger to India's punitive wrath. When Nepal was still a Kingdom, they had to deal with embargoes in 1969 -70 and the late 1980s. The 2015 unofficial blockade was merely a reminder of such instances in the past. The two key points that the EPG has mentioned – removal of Article 2 and regulating trade and transit – require discussion.

Article 2 of the 1950 treaty states that “[t]he two Governments hereby undertake to inform each other of any serious friction or misunderstanding with any neighbouring State likely to cause any breach in the friendly relations subsisting between the two Governments.” Though ambiguously worded, this clause places a fetter on Nepal's foreign policy. The Article has luckily never been invoked despite tensions between India and Pakistan as well as with China. Nepal has skilfully maintained its neutrality through all these rough patches. Though Nepal has been pushing to revive SAARC and form a trilateral understanding between China, India and Nepal, India's actions seem limited to countering both China and Pakistan.

On the issue of regulating trade and transit, the problem for Nepal comes down to numbers. Nepal at present has a population of around 29 million. The states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh with whom Nepal shares the longest border on the South have populations of around 109 and 219 million respectively. Free movement between countries while theoretically is not a bad idea, considering the practical aspects, Nepal quite legitimately fears that it could be demographically overrun. Though the national treatment clauses do not confer certain civil rights such as voting rights, sizeable lobbies of non-citizens can skew internal politics. A financially powerful group of non-citizens could technically influence a government's policy decisions. This is something that India too is dealing with regarding foreign contributions to political parties. Another aspect is that both countries grapple with corruption, which can potentially land non-citizens on voter rolls.

Therefore, a revised treaty with Nepal would go a long way in repairing the ties that were damaged through the blockade. Nepal on the other hand will probably be wary of considering the role India has historically played in the Himalayas. Sikkim's 'merger' has ensured the death of the treaty. The 2007 treaty with Bhutan has the appearance of a modern treaty between two sovereign states – it was signed by the Minister of External Affairs for India and the then Crown Prince of Bhutan. However, by virtue of the past treaty India still has a considerable grip over Bhutan's internal functioning. Nepal will have to consider all these variables when it finally proposes renegotiating the treaty, after the EPG submits its report.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.