The Migrant Sends Home Money and the Money Transfer Industry Steals It

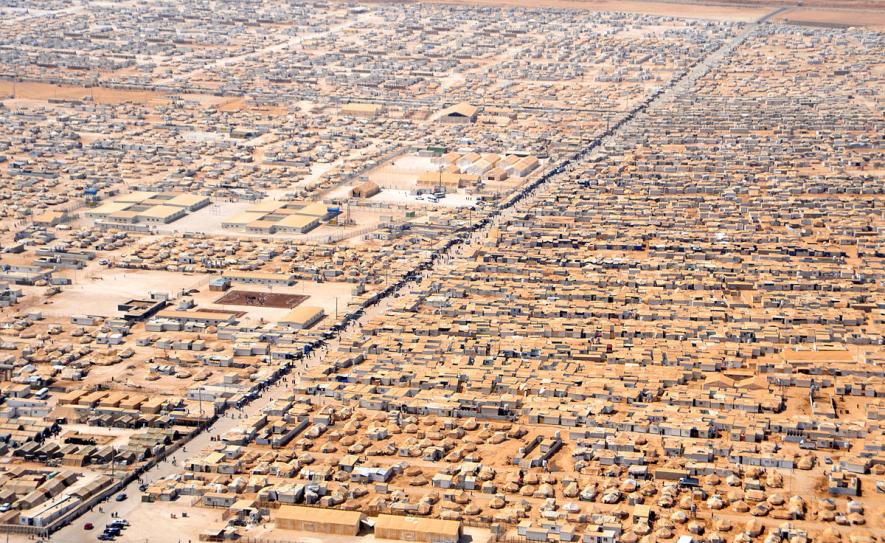

The Zaatari refugee camp – in Mafraq (Jordan) – has become almost a permanent home for refugees from the Syrian conflict. Many came here in 2012. A year later, the camp reached its maximum capacity of 60,000 – although it continued to swell. Along the main street of the camp are a series of shops that sell almost everything. The United Nations Refugees Agency (UNHCR) has produced a sophisticated way for the refugees to collect their allotments of food and supplies. Iris scanners link the shop to the UN database, bypassing the need for the refugee to carry cash, credit cards and vouchers.

At the edge of the camp are a series of small businesses that often money transfer services. These businesses – such as the al-Mafraq Exchange – provide services through Western Union to receive and send funds. Many Syrian refugees are fortunate to have one or another relative in the Gulf states, from where they are able to get small amounts of money to supplement what they get from the UN Refugees Agency. Many have relatives within Syria who are more desperate than them, and to whom these refugees send money. It is not clear how much money goes through camps like Zaatari, but one thing I can say from observation is that there are no camps of this kind that do not have money transfer agencies linked to them.

$613 billion in Remittances.

A small migrant caravan travels through Mexico on its journey towards the United States. Thousands of such caravans go across the Sahara Desert and the Mediterranean Sea towards Europe. This week, the bodies of seventeen migrants were found off the coast of Spain. Already at least two thousand people have died in the perilous Mediterranean crossing. The current number of displaced people stands at 68.5 million – more people than live in the United Kingdom and France. They are people who move out of desperation, but who come to new worlds where they work hard at jobs that are often difficult to do. The total number of people who live outside their country of origin is 258 million – which would be the fifth largest country in the world between Indonesia and Brazil. Europe and the United States panic about these migrants but need them when it comes to their labour.

What does the migrant do with the money that is earned in lands far from their homes? It turns out that they do not use this money for their own consumption, but like the migrants in the Gulf and in the Jordanian refugee camps, they send it to their families. This transfer of earnings across borders is known as a remittance. The World Bank found that global remittances reached a record high of $613 billion last year. Most of the remittances come from migrants who come from the Global South, work in the Global North and send the money back to their families in their home countries. What is remarkable is the percentage of money that some migrants send to their homes. Senegalese migrants in Spain, for instance, send almost half their earnings home, while Salvadorian migrants in Washington, DC send a more than a third home. Selflessness drives these migrants, whose own lives are surrendered for the well-being of their families.

A Quarter of their Gross Domestic Product.

The money that comes into the home countries provides these floundering states with enormous amounts of foreign exchange. The volume of remittances has grown astronomically – a fivefold increase since 1990. Some of these countries have come to rely upon the remittances for their own finances. The UN Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) shows that a quarter of the Gross Domestic Product for Haiti, Kyrgyzstan, Nepal, Tajikistan, Tonga comes from remittances.

So, the 2017 total remittances sent by working-class migrants to their home countries – mostly in the Global South - amounts to $613 billion. That same year, the total Overseas Development Assistance funds amounted to $142.6 billion. More money goes to countries such as Togo and Nepal from their emigrants than from the countries of the Global North – much more.

Fleecing the Migrant.

The volume of remittances compared to foreign aid is not the only scandal. The migrant has to send money through a money transfer service – such as Western Union or MoneyGram – or else through informal services (such as when family members travel home or through hawala, hundi and padala systems). The fees charged by these entities is usurious. There is no good data on the informal services. There has been a crackdown on these services because of the worries about terrorist financing. It is harder for migrants in the Global North to use these services, and when they do the fees are quite high as a consequence of the difficulties of maintaining these services. The crackdown on the informal networks drives migrants to the monopoly money transfer services such as Western Union.

Western Union is a money transfer firm that is worth $5.524 billion. It sends 31 transactions a second. This US firm dominates the money transfer business. When a migrant goes into a Western Union, the transfer service takes a substantial fee for the transaction. At time, this fee can amount to between 7% and 10% of what the migrant wishes to send. The World Bank found that the fee to transfer money to the countries of Africa amounts to 9.4%.

Of the money that the migrants wish to send to their families, $30 billion is taken each year by the money transfer industry.

The total annual budget for the UN Refugees Agency is $8 billion.

Bring the Fees to Zero.

In 2015, the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals included a discussion about the fees for remittance payments. The G8 (2009) and the G20 (in 2011 and 2014) suggested that the fees not exceed 5%. The UN’s Sustainable Development Goals suggest that the fees not exceed over 3% by 2030. These are distant goals. Impossible to imagine. The refugee and the migrant stands in the queue outside the MoneyGram and Western Union office, sending money out of their own desperation to family members equally if not more desperate as these monopoly money transfer firms squeeze their desperation into profit.

Neither are these migrants powerful enough to fight against this usurious system nor do their home countries help. Moral statements made by the G8 and the G20 as well as by the United Nations do not help. Groups like TIGRA try to raise awareness and provide modest ways to go around the high remittance culture of the money transfer industry. But these are no substitute for a global challenge to these high fees, this theft of money from the migrants and the refugees

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.