North Bengal: Women Becoming Hinges of Change

Image Courtesy: Flickr

North Bengal has always been a kind of hinge — the narrow corridor that connects the rest of India to the Northeast, a strip where everything seems to turn. But it also holds other hinges within it: the closed gates of the old tea gardens, and the new doors of opportunity that open to those willing to leave.

For decades, the hinges of life in North Bengal were the tea garden gates. Their opening and closing dictated everything. The work was never steady, the pay was never enough, but it was the only rhythm people knew. Now, that rhythm has been broken for good. Travel anywhere across the region, and you’ll see and hear stories of abandoned estates and shuttered gardens — reminders of an industry whose collapse has left thousands jobless.

This deep-seated vulnerability was brutally exposed by another blow: the recent floods. These damaged more than half of the tea estates, washing away homes, fields, and the fragile means of living that remained—not to mention the precious loss of life. For thousands already surviving on the edge, the floodwaters carried away the last vestiges of certainty, deepening a desperation that traffickers have long exploited.

The region's desperate need for economic opportunity has, historically, left its youth (particularly women) deeply vulnerable to trafficking . Here, the longing to cross a gate to a better life is so potent that it can be twisted into a trap. Women are recruited for "salon jobs" or "domestic work" in distant cities like Bengaluru or Chennai, only to find the gate slamming shut behind them, confining them to sex work, bonded labour, or illegal surrogacy. The journey begins with hope but ends in a captivity forged from poverty and the very desire to move forward.

And yet, within this same landscape, something quieter has been changing.

Over the past three years, more than 2,600 young people from North Bengal have joined short-term vocational training courses run by Pratham — brief programmes of six to eight weeks in automotive, hospitality, healthcare, IT, and beauty.

The profile of the enrolled is telling: Three out of four trainees come from tea-garden families. Eight in ten live in kaccha houses. Average household income barely crosses ₹6,500 a month. And yet, almost every youth enrolled owns a smartphone. In North Bengal, digital access has outpaced almost every other measure of living standards: tin roofs may leak, but a phone still glows in every hand. Notably, women lead the way, making up nearly 60% of all trainees.

Graph 1: Enrolment by gender

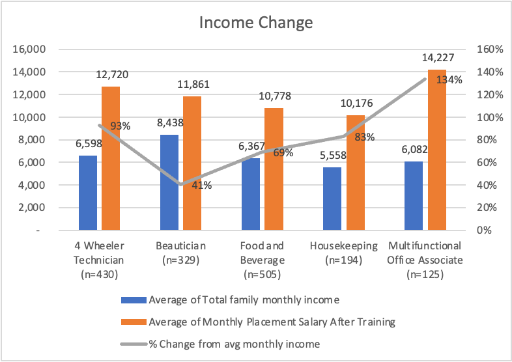

The outcomes of the training, however, speak louder than the courses themselves. About 70% of these youth find jobs. Placement incomes are, on average, 75% higher than the total family income of the youth. Some find work in hotels and hospitals, others in workshops or salons. Skill, it turns out, is still a hinge — a small joint that lets something larger move.

Graph 2: Income change after placement, by Industry

This migration is overwhelmingly outward-bound. Less than one in five placed youth remains in West Bengal; the rest travel to states like Gujarat, Maharashtra, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu. Kolkata—for all its history and size—employs barely 3%. This exodus is significant, especially given the region's history of trafficking: the same desperation to leave is now being channeled through legitimate pathways.

The financial incentive is undeniable. Those who move out earn nearly 70% more than those who stay. Beauticians from Alipurduar are employed in Chennai’s salons; hospitality trainees from Jalpaiguri serve in Gujarat’s hotels; and a group of twenty-six youth—25 of them women—now assemble semiconductors in Karnataka, earning ₹15,000 to ₹20,000 a month.

This pattern of migration reveals as much about West Bengal as it does about its people. The opportunities within the state remain limited; the willingness to seek them elsewhere is growing. The open phone and the closed factory gate coexist here, side by side — one promising the world, the other holding it back.

Yet, when you look closely at who is moving, learning, and staying employed, a quiet but powerful pattern emerges: women—long considered the most at-risk demographic—are becoming the region's most consistent earners.

The disparity begins with mobility. Among those placed, only 7% of women work within North Bengal, compared with 23% of men. The rest travel far, often alone, to states they had once only heard of. They are the same demographic once targeted by traffickers, now navigating legitimate channels of training and placement.

This trend solidifies with time. The data on retention reveals a stark and growing gap. At three months, 84% of women remain employed compared with 73% of men. The gap widens significantly by the six-month mark.

Table 1: % of Youth in Full-time Employment, by Gender

This higher retention is directly linked to migration. Jobs within West Bengal have the lowest hold: only 46% of youth placed there remain employed after 12 months, compared with 65% of those who moved out. The local economy offers little incentive to stay or room to grow. It is ultimately pushing its most ambitious workers—disproportionately women—to secure their futures elsewhere.

This is not a story of heroism, but of a slow shift in agency. Migration remains risky; wages are modest; homesickness is a constant companion. But unlike the journeys of the past, these begin with consent and skill, not deception.

In a region once defined by its closed gates, women have become the hinge of change—pivoting the community from a history of dependence to a new world of decision. The train routes that once carried stories of loss now carry stories of work. The same tracks that took women away in secrecy now lead to employment contracts and pay slips.

The writer is Senior Program Development Manager with the Skilling, Entrepreneurship, and Livelihoods arm of Pratham Education Foundation. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.