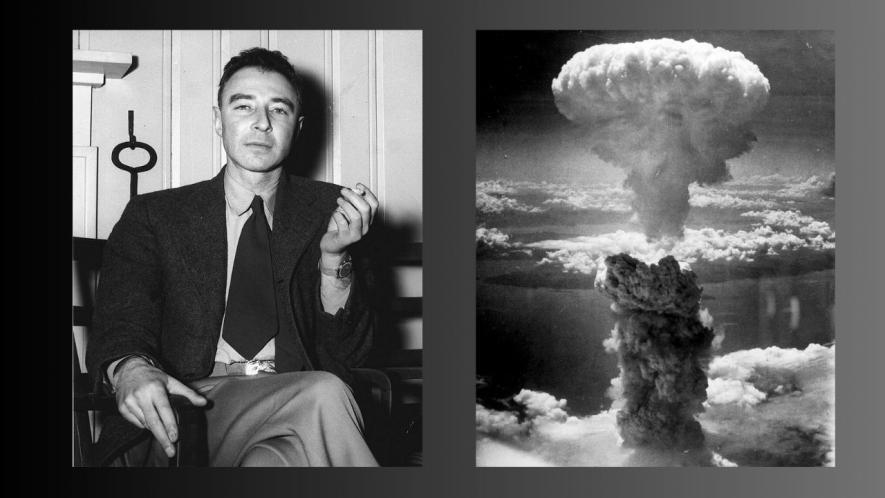

Oppenheimer Paradox: Power of Science, Weakness of Scientists

The new blockbuster film on Robert Oppenheimer has brought back memories of the first nuclear bomb dropped on Hiroshima. It raises complex questions on the nature of the society that allowed such bombs to be developed and used and which stockpiles a nuclear arsenal that can destroy the world many times over. Was the infamous McCarthy-era hunt for reds everywhere have any relationship with the pathology of a society that suppressed its guilt over the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and substituted it with a belief in its exceptionalism? And what explains Oppenheimer’s transformation from “hero” of the Manhattan Project that built the atomic bomb to villain and then forgotten?

I remember my first encounter with American guilt over the two atom bombs dropped on Japan. It was during a 1985 conference on distributed computer controls in Monterey, California. The hosts were the Lawrence Livermore Laboratory, which developed the hydrogen bomb. At dinner, a nuclear scientist’s wife asked a Japanese professor if his fellow citizens understood why the Americans had to drop the bomb on Japan—for it had saved a million American soldiers’ lives and many more Japanese. Was she seeking absolution for the guilt all Americans carried? Or did she want to confirm what she had been told and believed about the bomb? And did she believe that even the victims of the bomb shared those beliefs?

This is not about Oppenheimer the movie—it is about the atomic bomb Oppenheimer made, which created multiple ruptures in society. This new weapon completely changed the parameters of war. But not just that—it brought the recognition in society that science was no longer a concern of just scientists but of us all. For scientists, it also became a question that what they did in the laboratories had real-world consequences, including the possible destruction of humanity itself. It also brought home that this was a new era of big science that needed mega bucks!

Strangely enough, two of the foremost names of scientists at the core of the anti-nuclear bomb movement after the war also had a major role in initiating the Manhattan Project. Leo Szilard, a Hungarian scientist who had become a refugee in England first and then in the United States, sought Einstein’s help in petitioning President Franklin Roosevelt for the United States to build the bomb. He feared that if Nazi Germany built it first, it would conquer the world.

Szilard joined the Manhattan Project, though he was located not in Los Alamos but in the University of Chicago’s Metallurgical Laboratories. He also campaigned within the Manhattan Project to demonstrate the bomb before its use on Japan. Einstein also tried to reach Roosevelt with his appeal against using the bomb. But Roosevelt died and Einstein’s letter remained unopened on his desk. He was replaced by vice-president Harry Truman, who thought the bomb would give the United States a nuclear monopoly and, therefore, help subjugate the Soviet Union in the post-War scenario.

Turning to the Manhattan Project, it had a staggering scale, even by today’s standards. At its peak, it employed 1,25,000 people directly, and if we include the many other industries that directly or indirectly produced parts or equipment for the bomb, that number would be close to half a million. The costs, again, were massive: $2 billion in 1945 (around $30-50 billion today). Its scientists were an elite group that included Hans Bethe, Enrico Fermi, Nils Bohr, James Franck, Oppenheimer, Edward Teller (later the villain of the story), Richard Feynman, Harold Urey, Klaus Fuchs (who shared atomic secrets with the Soviets) and many more glittering names. More than two dozen Nobel prize winners got associated with the Manhattan Project.

But science was only a small part of the Manhattan Project. It wanted to build two kinds of bombs, one using a uranium 235 isotope and the other, plutonium. How to separate fissile material, U-235, from U-238? How to concentrate fissile plutonium? How to do both at an industrial scale? How to set up the chain reaction to create fission, bringing sub-critical fissile material together to create a critical mass? All these required metallurgists, chemists, engineers, explosive experts, and completely new plants and equipment spread over hundreds of sites. All of it was to be done at record speeds. This was a science “experiment” done not at a laboratory but industrial scale. That is why the huge budget and the size of the human power involved.

The United States government convinced its citizens that the Hiroshima and, three days later, Nagasaki bombings led Japan to surrender. Based on archival and other evidence, it is clear that more than the nuclear bombs, the Soviet Union declaring war against Japan led to its surrender. It has been proved that the claim of “one million American lives saved” by bombing Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which avoided an invasion of Japan, has no basis. It was a number conjured up for propaganda purposes.

While the American people presented these figures as serious calculations, what was completely censored were actual pictures of the victims of the two bombings. The only available photo of the Hiroshima bombing—the mushroom cloud—was taken by the gunner of Enola Gay, the plane that dropped the bomb. Even months after the nuclear bombings, when a few photographs of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were released, they were only of shattered buildings, none of the human beings.

The United States wanted to bask in its victory over Japan. It did not want that victory marred by visuals of the horror of the nuclear bombs. It dismissed people dying of a mysterious disease, which it knew was radiation sickness, as Japanese propaganda. To quote General Leslie Groves, who led the Manhattan Project, these were “Tokyo Tales”.

It took seven years for the human toll to become visible, only after the United States ceased its occupation of Japan. Even then, only a few pictures emerged, as Japan was still cooperating with the United States in hushing up the horrors of the nuclear bomb.

A full visual account of what happened in Hiroshima had to wait until the sixties. Then we saw the pictures of Hiroshima Shadows—the people who had vaporised, leaving only their traces on the stone on which they had been sitting; the survivors whose skin hung from their bodies, and of people dying of radiation sickness.

After the nuclear bombing, the scientists behind the bomb became heroes who had shortened the war and saved a million American lives. This myth-making converted the nuclear bomb from an industrial-scale effort to a secret formula discovered by a few physicists, giving the United States enormous power in the post-War era. This was what made Oppenheimer a hero for the American people. He symbolised the scientific community and its godlike powers. And it also made him the target for people like Teller, who later combined with others to bring Oppenheimer down.

But if Oppenheimer was a hero, how was he pulled down just a few years later?

It is difficult to imagine today, but the United States had a strong left movement before the Second World War. Apart from communists in workers’ movements, the intelligentsia—literature, cinema and physicists—had a strong communist presence. Scientists had embraced the idea, which JD Bernal had then argued in the United Kingdom, that science and technology could be planned and used for the public good. That is why contemporary physicists—then on the cutting edge of the sciences of relativity and quantum mechanics—also led social and political debates in and on science.

It is this world of science, a critical worldview, which collided with the new world where the belief was that the United States should be the exceptional nation and sole global hegemon. This hegemony could only be weakened if some people—“traitors to the nation”—gave away “our” national secrets. Any development anywhere else could be only a result of theft and nothing else. This campaign was helped by the belief that the atomic bomb resulted from a few equations scientists had discovered, which could, therefore, easily be leaked to enemies.

This was the genesis of the McCarthy era in the United States, its war on the artistic, academic and scientific communities and its search for spies under the bed. The military-industrial complex was taking birth in the country, and it soon took over the scientific establishment. In the United States, the military and energy—nuclear energy—budget would henceforth determine the fate of scientists and their grants. Oppenheimer needed to be punished as an example to other scientists—do not set yourself up against the gods of the military-industrial complex and our vision of world domination.

Oppenheimer’s fall from grace served another purpose. It was a lesson to the scientific community that no one was big enough to cross the security state. The Rosenbergs—Julius and Ethel—were executed though they were relatively minor figures. Julius had not leaked atomic secrets, only kept the Soviet Union abreast of the developments. Ethel, a communist, had nothing to do with spying. The only person who did leak atomic “secrets” was Klaus Fuchs, a German communist party member who escaped to the United Kingdom and worked on the bomb project there, followed by the Manhattan Project, which he joined as a part of a British team.

Fuchs made important contributions to the nuclear bomb-triggering mechanism and shared these with the Soviet Union. His contribution would have shortened the Soviet bomb, at best, by a year. As a host of nations have shown, once they knew a fissile bomb was possible, it was easy for scientists and technologists to duplicate it, as countries as small as North Korea have demonstrated.

Oppenheimer’s tragedy was not that he was victimised in the McCarthy era and lost his security clearance. Einstein never had a security clearance, so that need not have been a major calamity. It was his public humiliation during the hearings in which he challenged the withdrawal of his security clearance that broke him. Physicists, the golden boys of the atomic era, had finally been shown their true place in the emerging world of the military-industrial complex.

Einstein, Szilard, Joseph Rotblat and others had foreseen this world. Unlike Oppenheimer, they took the path of building a movement against the nuclear bomb. Having made the bomb, the scientists now had to act as conscience-keepers of the world against a bomb that could destroy all humanity—that bomb which still hangs as a Damocles Sword over our heads.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.