Pandemic Lowers India’s Level of Democracy

For nearly a month, lakhs of farmers have staged sit-ins on various points along the border shared by the national capital and neighbouring states. Their peaceful movement, which is drawing support from farmers across the country, is meant to persuade the government to repeal the farm-related laws that it pushed through Parliament in September.

The farmers have refused to accept the government’s claim that the new laws would benefit them. They insist that these laws would dismantle state procurement and open up agriculture to contract farming, which would only help big corporations. They have also been insisting that corporations will amass essential food commodities and manipulate stocks and prices, for the government has also revoked stocking limits.

The three laws were initially introduced as ordinances this summer while the Covid-19 pandemic was raging and the country was still segregated into red, green and amber zones. Thereafter, they were passed in Parliament without discussion or debate. The manner of their introduction—rather, imposition—threw all democratic norms to the winds and so farmers see no reason to trust the intention behind them either.

Farmers do not look forward to a time when large retail chains would dictate terms and impose conditions on them. They rightly say that these laws would usher in an attack on the right to food security of working people and escalate food prices, which would hurt all consumers.

The immediate response of the government to the concerns of farmers was to repress and distort their movement. Not a day has passed without fresh abuse hurled at them. Starting from “Khalistani” to “Urban Naxal” to “anti-national” to “fake farmers”, every trick in the book has been tried to stigmatise them. Nor have the authorities made serious efforts to stop those who are maligning this historic peaceful protest.

Yet it is also a fact that when confronted with the mass upsurge, including support for Indian farmers from western countries, the spree of abuses boomeranged on the government. To manage the situation in its own favour, the Centre began to level the charge that the movement is an “Opposition-sponsored” one. In other words, that it is politically motivated and therefore raises no substantial demands.

The joint front of around three dozen farmers’ organisations have flatly denied political parties any access to their platforms, nor have they indulged in politically-motivated speeches, actions or demands. All they are seeking is for the Modi government to repeal the laws which they see as a threat to their existence. Even the Supreme Court has said that protesters have a democratic right to raise their grievances peacefully.

Perturbed that the usual strategies—using which it has clamped down on the anti-CAA protests or student and youth-led movements—are proving ineffective, the government now finds itself in a bind.

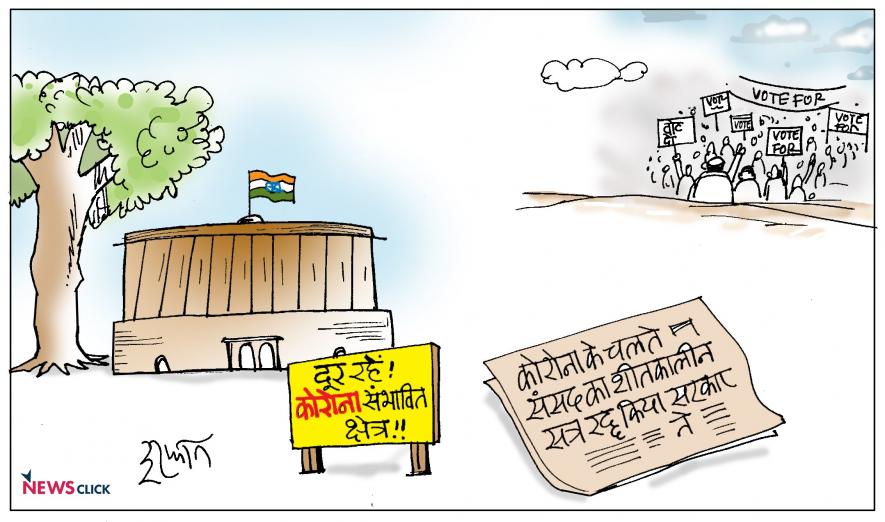

Now, as if blind to all other facts, the government has hit upon a new way to stall public discussion on the new laws. Worryingly, it has cancelled the Winter Session of Parliament—supposedly because of the pandemic. This is the same pandemic that did not force the government’s hand into postponing the Bihar Assembly election despite demands from the Rashtriya Janata Dal. If the rank and file of the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party could campaign in the Telangana and Jammu and Kashmir local body polls, then why is it restricting the normal—or truncated—functioning of Parliament?

The government has been claiming repeatedly that life is returning to normal although India has the world’s second-highest number of Covid-19 infections. Then why can it not hold one brief Parliament session—like the one it rustled up in September when it wanted a stamp of approval on the farm bills—to discuss the issues that farmers are raising?

Perhaps the government, despite its brute majority in Parliament, knows it is on slippery ground. The raging peasant struggle has generated a lot of unease among its close allies and also within the ruling party. A perception has taken hold that the Modi government is catering to the interests of select crony capitalists at the cost of all working people. Its dissimulation after the alleged Chinese incursions into Indian frontiers and its mismanagement of the migrant-worker crisis after the sudden lockdown have also come under the scanner. Even its demonetisation and GST ventures are being aired as its failures once again.

India’s former president, late Pranab Mukherjee, once said that the three essential “Ds of Democracy” are debate, dissension and decision. So, what does “New” India have if debates are consciously stalled, dissent is stigmatised and decisions are increasingly centralised in it? Is it still a democratic country? The CEO of the NITI Aayog, Amitabh Kant, has already told us that we are “too much” of a democracy. Then it would be safe just to say that democracy is shrinking in India. Or that India is moving towards “less” democracy.

That is certainly the message some recent developments send. Recently, a Metropolitan Magistrate who acquitted 36 foreigners associated with the Tablighi Jamaat who were accused of flouting Covid-19 protocols, said it was a possibility that the police had picked them up with a “malicious intention”. That the police, working “under the directions of the Union home ministry”, wanted to implicate them in the pandemic, as the editorial board of the Kolkata-based Telegraph recently wrote.

This acquittal is not the first in which a judge expressed strong displeasure against the targeting of an institution and its members. The Aurangabad bench of the Bombay High Court noted in August (as it quashed another FIR filed against Jamaat members) that a “political government tries to find a scapegoat when there is pandemic or calamity and the circumstances show that there is probability that these foreigners were chosen to make them scapegoats.”

The question arises, will those responsible for “scapegoating” a community and marginalising it even more, ever be held accountable? A large section of the media was complicit in the dubious operation to label the Tablighi Jamaat gathering at its headquarters in Delhi as an intentional super-spreader of Covid-19. Accusations against them, of hatching a ploy to spread the virus in India, damaged the country’s social fabric and increased the suffering of the minority community manifold. So, what kind of democracy does India have, if neither the media nor the State ever acknowledge their omissions and commissions?

The unabashed labeling of farmers, the “othering” of Muslims and worse things than these have been normalised to such an extent that no questions are being raised at all. Instead, anybody who questions the narratives being peddled by the government is lumped with the dissenters, intellectuals, activists, participants in mass movements. Being labelled anti-Indian is the price for seeking a different kind of India than the government of the day wants.

The author is an independent journalist. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.