Rajasthan: Spectre of Silicosis Continues to Loom in Bundi; Affected Workers Pushed Back to Mines in Absence of Opportunities

A stone-crushing factory in Dungarpur is causing distress for the local residents. Photo by Hrishi Raj Anand.

Bundi: People diagnosed with silicosis, a lung disease with no cure, in the Bundi district, are forced to labour in the mines for a meagre daily wage of Rs 100 due to a dearth of employment opportunities. The Welfare Board, although established on paper, offers no tangible support and a discrepancy in the relief fund leaves the workers bereft of assistance.

About 100 km from the city of Kota lies the small Bundi district, where sandstone mines claim numerous lives, according to reports. Citizens, barely 40-45 years old, await death in small village pockets, while the Board designated to provide relief fails to cater to basic necessities such as roads, water supply, and schools. Workers narrate how the lack of opportunities in the area drives their children into the same pit they are in. When there are no schools, colleges, and other job opportunities, the kids have no option but to work in the same mines.

In 2019, the Rajasthan state government came up with a landmark policy promised in the 2018 manifesto for pneumoconiosis (silicosis). The policy was meant to provide relief to over 25 lakh workers across Rajasthan who have no option but to sacrifice their lives to earn livelihood in their areas. The policy promises to grant a relief fund of Rs 3 lakh to every patient once diagnosed with silicosis and Rs 5 lakh upon their death. The policy promises a pension as well, although the document doesn't specify the amount, while patients claim to receive Rs 1,500 a month.

Prior to 2019, the compensation was Rs 1 lakh for those diagnosed with silicosis and Rs 3 lakh upon the person's death. As a result, workers diagnosed with silicosis before 2019 now receive significantly lower compensation.

At the sandstone factory, workers lack Provident Fund (PF) or Employees’ State Insurance (ESI) deductions and even ID cards, making it easier for employers to terminate them at any point, opening the door to exploitation.

Last year, the state government introduced a welfare board for silicosis to recognise and safeguard workers, addressing precautions typically ignored by mine owners.

In addition to this, the District Mineral Foundation Trust (DMFT), a body designated to work in mining areas, is supposed to use a share of profits generated from the mining industry for the well-being of affected areas and provide necessary compensation. The body is headed by a committee with the District Collector as the president.

As of now, there are 14,982 mining leases for minor minerals and 17,481 quarry licenses in the state. Additionally, sources suggest that there are hundreds of mines operating illegally as well.

The impact of silicosis on a villager from Bhilwara.

Silicosis is a debilitating illness. It poses a gradual and difficult journey for the workers. Over time, the ability to breathe diminishes until, eventually, the body gives in. Walking short distances becomes a struggle, and the health decline becomes evident as the patient's hands and legs shrink over the years.

In 2015, Murari was diagnosed with silicosis and received a one-time compensation of Rs 1 lakh as per the policy. He lives in Dhaneshwar village, which lacks farming or cattle opportunities. The entire area, including Dhaneshwar, Dabi, and Budhwara villages, is dominated by mines, leaving no other employment options. Depleting his funds, Murari, like many others with silicosis, had to return to the mines.

Murari was diagnosed with silicosis in 2015 and received a one-time compensation of Rs 1 lakh as per the policy.

Only this time, the employer was not bound to pay him the minimum wage. “When I went back to work, I was told that no matter what my condition was, I would only be paid as much as I worked. I accept that I am not very efficient at cutting the stone now, but he only pays me Rs 100-150 for a day’s work. Sometimes, not even that amount,” he said. Pension is not a reliable source of income either for people from Dhaneshwar. Many reported that they had not received the amount for the past three months.

Moreover, many workers who can't get bank loans take advance payments from companies for family events or emergencies. This obligation forces them to work without pay until they've repaid the amount through labour.

The area lacks basic essential amenities, and central government flagship schemes are conspicuously absent. Despite more than half of Dhaneshwar village applying for the PM Awas Yojana in recent years, their names were never approved. They pay a monthly water bill of Rs 200, even though DMFT is in place, which could have facilitated a pipeline in the area. With a population exceeding 5000, there's only one school, lacking the necessary teachers and pushing the children of mine workers into the same business that is claiming their parents' lives.

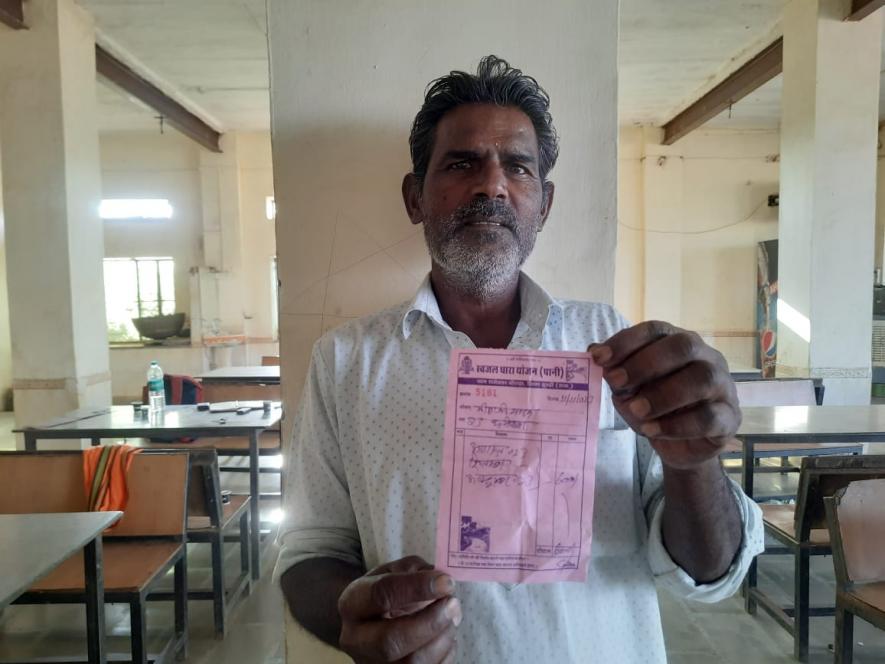

Despite the DMFT in place and central schemes promising water in every house, villages in Bundi still pay Rs 200 a month for drinking water.

The role of DMFT is seldom scrutinised, but the structure of the organisation appears flawed. Neither the village Pradhan nor the villagers are involved in decision-making for their benefit. This situation persists in all other villages in the area, including Dabi and Budhpura. Although the website of this body claims responsibility for creating alternative employment opportunities, particularly for silicosis patients and widows, no tangible efforts can be seen on the ground.

The state government proudly announced the welfare board for silicosis last year, becoming the first state to take such a step. However, the Board's role has been restricted to gathering names of workers and their associated companies. In some areas, even this hasn't been accomplished. The recognition needed to safeguard the rights of workers is still absent a year and a half after the creation of the Board. With each day passing without the board's proper functioning, a number of workers continue to suffer under the weight of oppression and face the threat of death.

In the nearby tribal district of Dungarpur, there are stone-crushing factories that operate in the open, risking the lives of passersby and the villages lying within a radius of a kilometre from these mines.

Ashok, a local resident, drives a dumper carrying waste from these stone-crushing factories. However, he often has to migrate to Gujarat to make ends meet. This is because, he alleged, the mines in the area refrain from hiring locals. Most of the workers in these mines are the ones who have migrated from Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, and other states.

Similar to the textile industry in Bhilwara, employing migrants enables factories to exploit workers with lower pay and extended working hours. Moreover, it provides an easy avenue for firing and sending them back, escaping the obligation of compensation. The fact that workers come from different states gives factories leverage to disregard legal regulations.

For a state so rich in minerals, little is being done to protect the workers who put their lives at stake and in turn, keep the state’s economy running.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.