Record Harvests; Still Why Are Prices of Wheat, Rice So High?

Image for representational purpose. Credit: PTI

A bizarre and ominous situation prevails in the country’s foodgrain scenario. There have been successive record harvests of rice and wheat, and also of various nutri/coarse cereals, according to second advance estimates of the agriculture ministry released earlier this year. Even total production of pulses is at record levels though some of the pulses (like tur/arhar) are a bit down. Through a series of measures, the government has prevented too much exports. A significant amount of procured wheat has been sold by the government in the open market.

So, all this foodgrain is inside the country. Yet, prices of staples like wheat and rice, and also of pulses continue to remain high, blowing a devastating hole in the family budgets of common people. The even more worrying thing is that the government doesn’t seem to have a plan or a strategy for bringing down the prices. There are key Assembly elections slated for the end of the year and then there is the Lok Sabha election coming up early next year. One would think the government will be concerned. But it seems to have exhausted its options. How has this shocking mess occurred? More importantly, what can the government do to bring down retail prices while ensuring that farmers get at least the minimum support prices fixed?

Prices of Food are on Fire

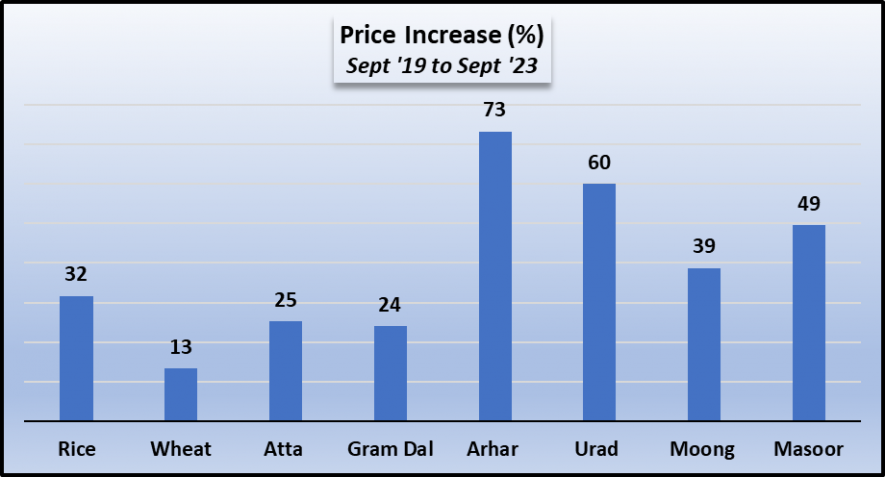

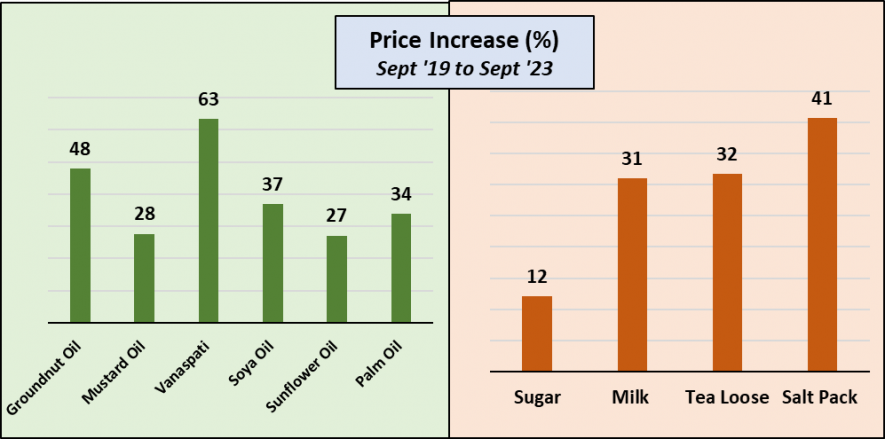

Although Consumer Price Index data put out by the government showed some easing of inflation in food items in August 2023, the reality is that over the past few years, net price rise has been intolerably high, as shown in the charts below. These are based on the government’s department of consumer affairs daily data collected from across the country.

Between September 21, 2019 and September 21, 2023, rice prices increased by nearly a third, wheat by 13% and wheat flour (atta) by about a quarter. Prices of all the pulses, which are an important source of protein for Indians, have increased unbearably, with tur/arhar increasing by 73%, urad by 60% and masoor by 49%. (See chart below)

This price rise in staples should be seen in the context of similar price rise in other food items like cooking oils, milk, and even salt. (See chart below)

The family spend on food has become all the more unbearable because the government also decided to stop the free supply of 5 kg foodgrain to all ration card holders (and others), a scheme started in 2020, during the pandemic.

Production is Increasing

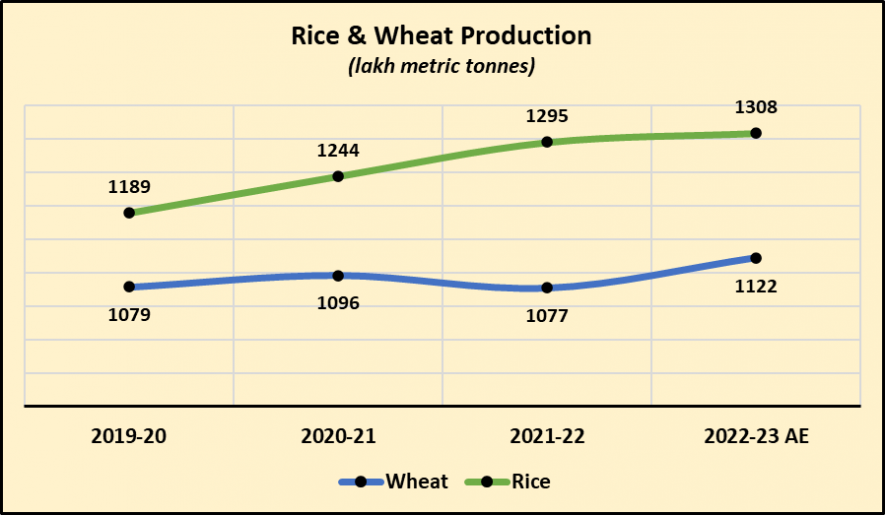

Some may think that various weather upheavals like heat waves and excessive rains have caused a shortfall in production, leading to less supply and hence higher prices. This thinking has been encouraged by media reports. But, as shown in the chart below based on government data, rice and wheat output is continuously rising. Since 2019-20, wheat output has risen by 4% and rice by 10%. The government claims every year that record production has been achieved.

For pulses, output has increased by over 20% - from 230 lakh metric tonnes (LMT) to 278 LMT, over the same period.

Clearly, it is not shortage of production and reduced supply that is causing sustained higher prices in the past few years, especially since 2022. There is something else at work.

What has Govt Done to Control Prices?

Administrative measures include banning wheat exports in May 2022 and then banning the export of atta and other such products in August 2022. This caused an uproar because just a few weeks before the ban, the government itself had vociferously urged that the export of wheat should be scaled up to take advantage of the global shortage of wheat caused by the Ukraine war. This, however, had very little impact on domestic prices which continued at high levels. From June 2023, traders, millers, wholesalers, and retail chains have been prohibited from holding more than 3,000 tonnes of wheat, while for small retailers, a stock limit of 10 tonnes has been put into effect. Reportedly, such measures have been taken for the first time in 15 years.

In the case of rice, the government banned export of non-basmati rice this year. It imposed a 20% export duty on parboiled rice. It fixed a minimum export price for basmati to deter traders from exporting it.

Much reliance was placed on selling wheat and rice from government’s own stockpile which, the government claimed, would help bring down prices. In June this year, it announced that 15 LMT of wheat and 5 LMT of rice would be sold in the open market. Then in August, it announced that an additional 50 LMT of wheat and 25 LMT of rice would be sold to bulk buyers through its Open Market Sales Scheme (OMSS). The latest reports say that the government has sold 18 LMT wheat has already been sold in the open market through 13 rounds of e-auctions.

All this has failed to bring down prices significantly. This is partly because the volumes are too small to affect overall prices and also because these sales are being taken advantage of by bulk buyers (like biscuit, bread, or snacks producers). Neither the farmers nor the consumers of wheat and rice are benefitting.

What Could Have Been Done?

The biggest policy mistake made by the government is not pushing up procurement and routing the foodgrain into the Public Distribution System at subsidised rates. As per the latest figures available from Food Corporation of India (FCI), rice procurement till September 13, 2023 was 569.46 LMT in the Kharif Marketing Season of 2023-24, compared to 575.88 LMT in the previous season. For wheat, procurement stood at 262 LMT, compared to 187.9 LMT last year, but way below the level of 433 LMT reached in 2021-22.

Wheat procurement dipped drastically last year and although it has increased a bit in the current year, it is clearly much below the norms of years prior to that. Despite record harvests, procurement dipping is a sign of the government’s inability – more likely, unwillingness – to procure. It is thus depriving farmers of MSP and simultaneously allowing prices to rise in the open market. If the government had procured more and channelled it to the people at subsidised prices, open market prices would have automatically dropped. Instead, it is wringing its hands and huffing and puffing about open market sales – which are in fact going to bulk buyers, not the hapless common people.

Since the government doesn’t seem to have any other strategy on the anvil, and in fact, it is busy pretending that there is no crisis, the prospects for the future look bleak. Prices will continue to remain high, and with no sign of general inflation going down, people will continue to suffer because of mismanagement.

Perhaps it shouldn’t be called ‘mismanagement’. The situation is a direct result of policy choices made by the government which has repeatedly talked of curtailing subsidies, minimising government intervention in governance, encouraging the private sector to run the economy, reducing public expenditure and – specifically – getting rid of the procurement and distribution system for foodgrain. The three agriculture-related laws that it passed in 2020 (which it was forced to roll back in 2021) envisaged just this set-up that is today being smuggled in by acts of omission. And, the results are precisely what was feared – high prices for consumers, low prices for farmers, a boon for corporate bulk buyers and traders.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.