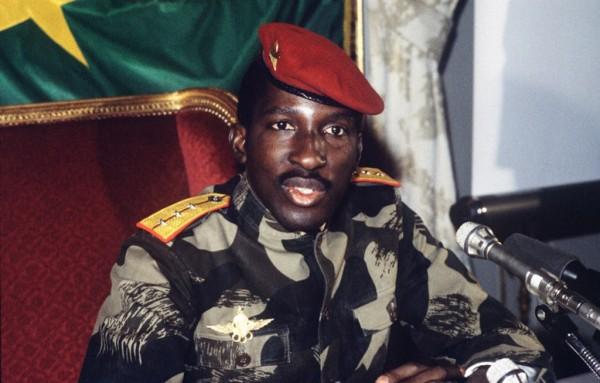

Remembering the Che Guevara of Africa: Thomas Sankara

President Sankara stood up and announced to his ministers - lets go out and eat lunch together at a restaurant. The ministers applauded in apparent pleasure, until he named the restaurant: Yidigri, a restaurant serving mostly low-income clientele near the Yalgado Hospital. After lunch, he announced that each minister would pay their own bills—along with the bills of their chauffeurs. The event was intended to be a lesson in collectivism, unpretentiousness and generosity—all pillars of his political praxis.

Thomas Isidore Noël Sankara, known as Che Guevara of Africa (1949-1987), was assassinated 30 years ago -- on 15 October, 1987. He was one of the most outspoken anti-imperialist leaders of the late 20th century. Following a series of coups and counter-coups that eventually led Thomas Sankara and his comrades to power in 1983 in Burkina Faso, an extraordinary revolution was launched.

"Thomas knew how to show his people that they could become dignified and proud through will power, courage, honesty and work," his widow, Mariam Sankara, told Jeune Afrique magazine.

To mark his first year in office, Sankara changed the country's name from Upper Volta to Burkina Faso, meaning "the land of the upright people". An accomplished guitarist, he wrote the new national anthem himself.

Burkina Faso, which was once French colony, obtained independence in 1960. This tiny, impoverished country, had an illiteracy rate of 90%, the world’s highest infant mortality rate (280 deaths for every 1,000 births), inadequate basic social services, one doctor per 50,000 people, and an average yearly income of only $150 per person. When Sankara took over, it was even unable to feed its population.

Sankara policies soon changed the landscape of a country. In the space of just four years, the country became self-sufficient in food, its infant mortality rate halved, school attendance doubled, 10 million trees were planted to halt desertification, and wheat production doubled. Land and mineral resources were nationalised, railways and infrastructure constructed, and 2.5 million children immunised against meningitis, yellow fever and measles.

Firoze Manji, a Kenyan writer and journalist says:

Nearly 350 medical dispensaries and schools were constructed across the country by communities. In order to achieve this Sankara did not ask for aid – on the contrary, he shunned it. Moreover, he argued that the debt owed by the country was odious and therefore should not be paid. Cotton production therefore was not directed to export but was used to support a thriving textile industry. The country was marked in particular by the almost complete absence of foreign aid agencies and their local counterparts, the development NGOs.

In terms of revolutionary movements in Africa, Sankara’s stands out, not only because it occurred well after independence, but also because of the ambition of its vision. Sankara was a militant economic revolutionary who aimed to achieve social justice at home through a prioritisation of food justice, while recalibrating Burkina Faso’s place in the international system.

During an interview with Jean-Philippe Rapp in 1985, Sankara said:

I would like to leave behind me the conviction that if we maintain a certain amount of caution and organisation we deserve victory [....] You cannot carry out fundamental change without a certain amount of madness. In this case, it comes from nonconformity, the courage to turn your back on the old formulas, the courage to invent the future. It took the madmen of yesterday for us to be able to act with extreme clarity today. I want to be one of those madmen. [...] We must dare to invent the future.

For Sankara, praxis was the base for politics. He prioritised the politicisation of non-elites and non-specialists in a determination to do, make, and effect social change.

He was one of the first leaders in Africa to recognise that key to the development of Burkina Faso and Africa was improving the status of women. Sankara appointed women leaders to major cabinet positions and to recruit them actively for the military. He outlawed forced marriages, forced general mutilation (FGM) and encouraged women to work outside the home and stay in school even if pregnant.

Amber Murray, in her book A Certain Amount of Madness” The Life, Politics and Legacy of Thomas Sankara” writes:

As he reminded the audience during one speech- What is left for us to do is [to] make the revolution!” Revolution, for Sankara, was more than a ‘passing revolt’ or a ‘simple brushfire.’ Rather, the political economy of Burkina needed to be ‘replaced forever with the revolution, the permanent struggle against all forms of domination’.

Rejecting the idea of aid, Sankara blamed this “White Saviorism” (as Manji calls it) for victimising the people of Burkina Faso as well as for stripping them of agency. This stripping of agency occurred on multiple levels: it was both intellectual, through the insinuation that local solutions were unlikely (this was a form of mental colonisation), as well as tangible, through the suppression of an environment in which people’s own creativity could lead to innovative responses to local dilemmas.

“Our economic aspiration is to create a situation where every Burkinabè can at least use his brain and hands to invent and create enough to ensure him two meals a day and drinking water”, said Sankara.

Sankara was clearly aware of the immensities and dangers of the revolutionary project before him. He knew that he would be perceived as a “madman” for fighting against a powerful global and regional economic elite.

After just four years and two months as president, Sankara was assassinated by Liberian mercenaries who had been trained in Libya, with ideological support from Cote D’Ivoire, France and the US, under the leadership of Blaise Compaoré. On October 31, 2014 almost exactly 27 years after Campaoré killed Sankara, he was overthrown by a mass upring in Burkina Faso that drew inspiration from Thomas Sankara.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are the author's personal views, and do not necessarily represent the views of Newsclick.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.