Remembering Girish Karnad, who Cultivated Reason in a Jingoistic World

I never had the good fortune of knowing Girish Karnad personally or meeting him. Like many others, my acquaintance with him was through his drama and activism. As Virginia Woolf writes in Orlando, “Every secret of a writer’s soul, every experience of his life, every quality of his mind, is written large in his works.” Karnad is no exception to her observation since his work is the cultural zeitgeist of post-Independence India. His works resonated with his audience in a voice that was deeply personal and political at the same time.

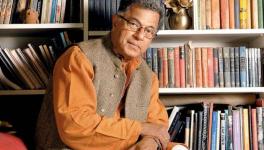

An actor, director, critic, scholar, activist and playwright, Karnad was a polymath who donned so many hats all his life that it is difficult to peg him to a single role. For me, however, Karnad was, first and foremost, a playwright par excellence. In fact, he once confessed that he would like to spend the rest of his life doing what he did best—writing plays.

During my university days, I got several opportunities to perform Karnad’s plays, including Agni Mattu Male (The Fire and the Rain), Nagamandala (Play with Cobra) and Hayavadana. As an actor and a teacher, I believe that the most effective way to understand a play is by performing and experiencing it unfold before one’s eyes. While a performance may evoke the audience to create their meanings, it may go well beyond the authorial intent, irking the playwright. Karnad, however, was a different soul. He believed every performance was a palimpsest offering itself fresh each time it was performed. That is why he was not perturbed when Ebrahim Alkazi, the ‘godfather’ of post-Independence Indian theatre, took Tughlaq outside the confines of a proscenium to the Purana Qila, ripping away the play’s form.

Karnad was open to change and eager to learn. In his Hayavadana, he did away with the masks initially reserved for Devadatta and Kapila, as he realised the challenge it imposed on the actors performing these roles.

After my PhD, I got to teach Karnad to university students for the first time. I could not have asked for more! I was to teach my favourite writer who had kept alive the performer in me. I was excited and eager to do as much Karnad as possible in a limited time. But my dream was to shatter soon. Dishearteningly, most students told me they had not heard about Karnad, let alone his plays. I was not sure how social-media buffs, not used to reading dramas, would take to his plays, mainly because the context in which Karnad had written was temporally and spatially so very different from their own. However, the response Tughlaq evoked among them was completely unexpected. To my surprise, not only did they enjoy its dramatic readings, but they also interpreted the play in their present social and political contexts. Needless to say, they would want more of Karnad by the end of the course. (The next offering was Karnad’s Hayavadana.)

Karnad began writing in an era when Indian theatre was struggling to find a way for itself. His generation of playwrights included stalwarts like Vijay Tendulkar, Habib Tanvir and Badal Sircar, who were trying to create a new idiom of drama in Marathi, Chhattisgarhi and Bangla. Karnad, writing in Kannada in the 1960s, typified the dilemma of a postcolonial writer who was to negotiate the “tension between the cultural past of the country and the colonial past”. It was indeed challenging to create a theatre that is modern yet not Western, a theatre that took the best from both traditions, Indian and Western.

His biggest contribution to Indian theatre was blending its cultural and colonial past seamlessly. His range was eclectic, drawing from history to folklore and mythology to contemporary society. While he looked towards the Indian cultural past for inspiration, his plays had a contemporary sensibility. Hayavadana, for instance, borrows heavily on the Kannada folk form of yakshgana and the plot from an 11th century text Sanskrit Kathasaritasagara but the play is neither a folk drama nor a dated one. It’s a modern play, sophisticated in form and content. The play is quintessentially ‘Indian’, for it represents the postcolonial quest for relevance.

Karnad’s other fascination was history. Inspired by the history of the Deccan, he wrote three history plays—Taledanda (1990), The Dreams of Tipu Sultan (1997), and Crossing to Talikota (2019)—on themes that have heavily influenced Indian culture and politics since the 12th century. However, his most successful and oft-performed history play is Tughlaq (1964), based on the reign of Sultan Muhammad bin Tughlaq. It is every actor’s dream to perform the titular character at least once in their career. Written in 1964, Karnad explored medieval Indian history to create this masterpiece. Though set in 14th-century Delhi, the play is steeped in contemporaneity. Karnad has wonderfully revealed the parallels between the two decades of Tughlaq’s reign and the first twenty years of Indian Independence. Though not overtly political in its theme, Karnad has suggestively commented on the failure of the Nehruvian socialism, “The gradual erosion of the ethical norms that had guided the independence movement, and the coming to terms with cynicism and realpolitik”, by his admission.

While the play is significant for its covert political commentary, it is even more noteworthy for suggesting an alternative reading of Tughlaq the Sultan. Karnad’s Tughlaq is neither the orientalist historian’s Tughlaq nor the nationalist historian’s Tughlaq—both of whom would conveniently decry him and portray him as a “Mad Sultan”. His Tughlaq is the story of a king’s downfall from idealism to opportunism. While Karnad does not justify Tughlaq’s violence, what he offers is a sophisticated and nuanced psychosocial understanding of Tughlaq’s subjectivity.

Karnad might have left this world but left it richer with his ideas, values and ethics. In today’s world of jingoism and bigotry, it’s only too relevant to listen to the voice of reason and tolerance Karnad promoted through his life and writing. Nothing better can eulogise a life that inspired lives.

The author is an assistant professor of English at Ambedkar University Delhi. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.