Rise and Fall of the Original Angry Young Man

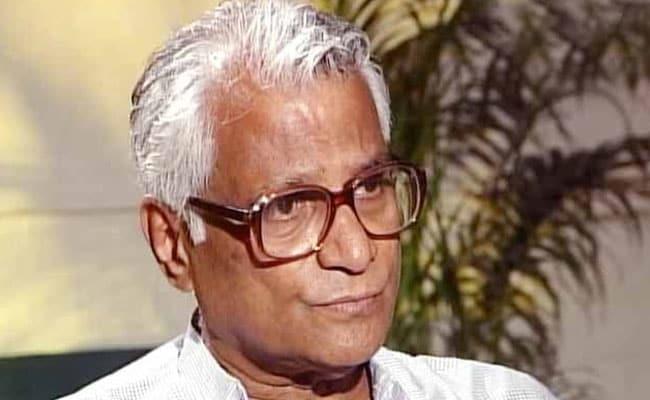

Image Courtesy: NDTV

I could never call him “Georgesaab”. It seems odd to call him Mr. Fernandes. For me, he was always George. And would remain so. Just like Dilip-Raj-Dev, or Sunil, or Lata. George was our original angry young man, even before actor Amitabh Bachchan could assume the role on screen.

I first saw George when I was about eight years old. His union office was right opposite where I lived as a kid in Mumbai’s Girgaum. George had just won the 1967 Lok Sabha elections, and made an impression across the country. His opponent, SK Patil, at the time, virtually owned Mumbai, or Bombay as it was called back then. Patil was in charge of finances in Congress party, and his influence in the city dated back to Jawaharlal Nehru’s Prime Ministership. He had money and muscle at his disposal, which made him invincible in the eyes of the pundits. But George managed to capsize Patil, with the help of people on the ground. What he executed during that elections would later be known as political marketing. The stories of his oratory and mobilisation began spreading like a forest fire after the elections.

It was obviously a thrilling experience to witness a new hero. George questioned the status quo, he challenged the quintessential image of a politician. Messed up hair, wrinkled clothes, but personality brimming with enthusiasm. He had the walk of a man who believed he could change the world. It is not surprising that an entire generation was enamoured by his rebellious demeanour, which reflected in his speeches that would begin in English, and would touch Marathi, Hindi, Kannada and Tulu by the time they ended. But the outcome was always consistent. The crowd would leave mesmerised.

I think of images when I think of George. And there are plenty when I look back at his career that lasted five decades. The image of George, drenched in outpouring rain, addressing the Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation workers, or of him getting beaten up by the cops on a railway track, or the iconic image where George is in handcuffs during the Emergency, or taking oath as a minister, or the image of him sitting with Atal Bihari Vajpayee-L K Advani...

The question I have been grappling with is who is the real George? The one who asked Coca-Cola to leave, the one who met jawans in Siachen, or the one who defended Graham Staines’ killers? The charismatic rebellious leader I met in Bombay, or the man who later became part of the system?

George’s life could probably be divided into two parts. Pre- and post-emergency. He was admitted by his father to a seminary in Mangalore to serve the church, where the seeds of rebellion were first sown. The father in the church kicked him out of the seminary after he was suspected of having tuberculosis. George’s father got his check-up done and sent him back. By that time, though, George had been overcome by anger against the seminary. He ran away to Bombay, to never play the religion card again. I can’t think of another contemporary politician who transcended geography, religion, language like George did. He was Christian, but he never played the minority card. He was born in South India, but his work centred around West and North India. He was a living example of the secularism that Nehru had envisioned for India.

George’s journey in Mumbai is straight out of a movie script. It has always been a dream city that doesn’t disappoint the hardworking. George was no exception. P De’Mello and Comrade SA Dange were the biggest labour leaders in Mumbai at that time. The Mangalore connection probably helped, De’Mello spotted the spark in George, and took him under his wing. Socialists got their star leader who broke communist hegemony over the financial capital.

Working as a waiter in a hotel, sleeping on the footpath, George focussed on the unorganised labour in the city that hadn’t even imagined a union of their own. Hotel workers, cabbies, BEST and BMC workers. They learnt of their rights because of George. Even after addressing wee hour rallies with hotel workers, he would be ready for an early morning meeting of BEST workers at the depot. Most importantly, he ensured class IV employees, mostly manual scavengers, who would only be subjected to contempt, got the voice of their own. When poor taxi drivers wouldn’t get bank loans, he started a labour bank and ran it successfully. He had given space in his office for Namdev Dhasal’s sex workers union as well.

But he often regretted the fact that he couldn’t assure societal respect for the scavengers. Their rights remained confined to finances. He would say so in as many words, but by then, in 1980s, his unions had turned into ’shops’. His trusted lieutenant Sharad Rao took over the unions from him and finally left him.

But the unions ended up being his key to Delhi. He could shut Mumbai down with the ease of a man using a switch. He had the sense of when and where to pull that string. Media named him ‘Bandh Samrat.’ Bal Thackeray later gave bandh a bad name by making it violent. Congress used its muscle to divide his unions, but the workers in Mumbai were too loyal to George for that to happen.

George adopted anti-Congress ideology through his Guru, Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia, and later socialists ideologue Madhu Limaye. But his Congress hate went too far around the Emergency in 1975. Maybe the way Indira Gandhi smothered the 1974 railway strike proved to be the trigger. But that is no justification to veer away from Gandhi-Lohiya’s path of non- violent resistance. George conspired to plant explosives across the country which was known as the ‘Baroda Dynamite Case’. In fact, he had even thought of bumping off Indira and her younger son, Sanjay Gandhi, but was stopped by his colleagues. If Janata Party had not formed the government in 1977, George would have been convicted, and hanged to death. George always defended his act vehemently. He was ready to go to any lengths to save democracy. The irony was lost on him. He had justified it by saying it was the need of the hour, which became his shield since then. It was the beginning of a tragedy.

When George won a landslide in 1977 from jail, it was the peak of his popularity. Within 19 months, as the government collapsed, he had turned into a villain. He backstabbed Morarji Desai, after promising to support him.

Initially, George was opposed to merge Socialist Party with Janata Party. He was opposed to becoming a minister, too. Finally, he accepted it. After which he ended up becoming a minister thrice. Industry Minister in the Janata government, Railway Minister when VP Singh was the Prime Minister, and Defence Minister under AB Vajpayee. He ensured he left a stamp on each of the portfolios he held. His decision to ban Coca-Cola resulted in the birth of Thums Up. Today, we would have called it Make in India.

As Railway Minister, George conceptualised the Konkan Railway, and as Defence Minister, he was respected among the jawans. He didn’t exactly get along with the bureaucracy that made several attempts to defame him. Tehelka expose and Coffin scandals almost destroyed him. He was in a fix. He detested power, but couldn’t leave it. He was most comfortable with people’s movements. Which is why, he had opened the doors of his ministerial residence to human rights activists. It was objectionable, but that was the real George. The George from Bombay.

Allying with Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was a desperate move for him to stay relevant. “I am helpless,” he told his colleagues. Post-Mandal, he had become irrelevant in Bihar. He had antagonised Lalu Prasad Yadav and sided with Nitish Kumar. The alliance with BJP helped him and his party survive. He had good relations with Vajpayee and Advani, which prolonged his political career by 10 years. The Sangh Parivar used him to their advantage. But it came at the expense of his fighting spirit.

That was the period where his followers had gotten disillusioned with him. But two moments that totally shattered his reputation were his justification of Graham Staines murder in 1999 and Narendra Modi’s defence after the 2002 riots in Gujarat. It was hard to believe he was the same man who had travelled through Mumbai during 1992-93 riots to establish peace. He had condemned the Babri Masjid demolition. When Bal Thackeray had attacked my reporters at Mahanagar – the newspaper I ran in Mumbai – he wrote a letter chastising him for his actions. A clear stand against communal polarisation was expected from him. But when he sided with the culprits, that marked the end of the George I knew.

Yet, his condition in the past few years kept gnawing at me. A towering personality once, was all alone, fallen prey to Alzheimer’s. I would often wonder why George had to go through it towards the end of his life. Was it destiny’s revenge? Or is that the climax of every tragedy?

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.