Roots of India’s Tradition to Silence Critical Voices

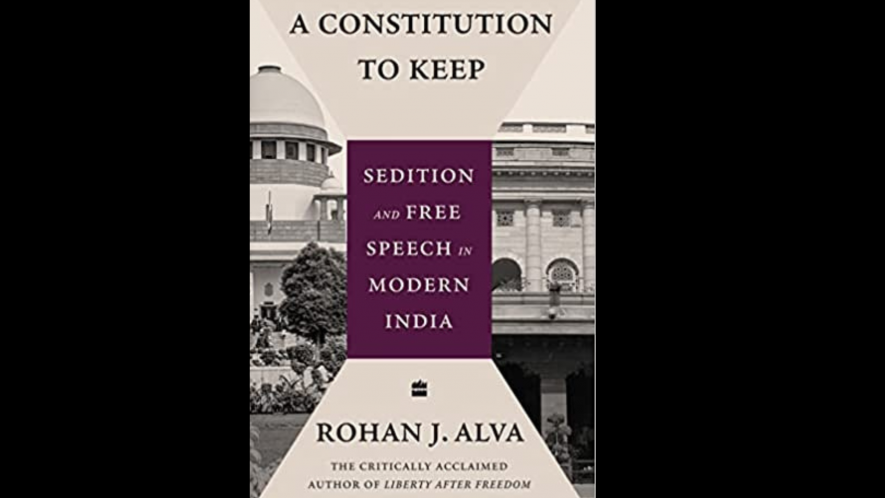

Image Courtesy: Amazon

Rohan J Alva’s latest book, A Constitution to Keep: Sedition and Free Speech in Modern India, is an indictment of sedition law in India. His last book, Liberty After Freedom: A History of Article 21, Due Process and the Constitution of India, was a refined analysis of the evolution of due process in India after the drafting committee “unceremoniously abandoned the due process” although the Constituent Assembly had accepted it with a thumping majority.

The latest book is divided into 14 chapters and three timelines, the colonial experience, followed by the gestation period of the Constitution and the period of constitutional democracy. Alva embarks on the journey by tracing the rise of the Crown’s influence in India. The Charter Act of 1833 mandated the governor-general, William Bentinck, to consolidate and codify laws in the territory. As a result, the first Law Commission was established in 1834, and laid its report in 1837, which became the first draft of the Indian Penal Code of 1860.

History of Manifesting Sedition as Political Tool

The author begins with a scathing remark on the farce of creating uniformity under the rubric of modernising the existing criminal justice systems, especially when the English criminal justice system launched in Britain could now execute people for trivial crimes. The Royal Commission Into the Operation of Poor Laws of 1834 observed that the English legal system “lacked coherence”. Alva contends it was a social-legal experiment that the Law Commission subscribed to under the garb of modernising its “primitive criminal justice system” in India, to hold up “a mirror to the island’s own legal system mired in chaos”. This can be further substantiated as James Fitzjames Stephen, a member of the British viceroy’s council in India, who was called to the British Parliament in 1877 to share his experiences with codifying laws in India and how they could bear upon the effort to codify English law.

Sedition was conceived in the initial penal draft, though loosely constructed. Alva observes that the nebulous word “disaffection” in the provision had no definitive meaning, illustration or uniformity in punishment—one could either get banished for life or face incarceration for three years. The version of sedition introduced by Macaulay was even more vexatious than its counterpart in England. Its etymology can be traced to the Latin word sedition, meaning riot, but in India its significance was devoid of actual upheaval and could be used in instances of mere criticism of authorities. The provision was further aggrandised by the interpretation given to the word disaffection in the Bangoobasi, Bal Gangadhar Tilak (first t), and Amba Prasad cases. It was construed in varying degrees, beginning from hate, contempt and ill-will to lack of affection towards the government and down to disloyalty.

The need to stifle dissent was perceived as a sine qua non to the Crown’s sustenance in India. The Gagging Act of 1857 was enacted months after crushing the rebellion. As the name suggests, it sought to gag the free press, and was followed by the Vernacular Press Act of 1878. Alva contends the regime was transparent about its intention—enforcing obedience and the sovereignty of the crown, for which it would curtail the liberties of the Indian subjects to the maximum. Moreover, the British were paranoid that a conspiracy to wage a civil war was brewing. As a result, a penal statute that remained dormant for decades was hurriedly enacted. The provision of sedition, dropped from the penal law because of some “unaccountable error”, was re-inserted in the draft a decade later to quell future rebellions.

By the end of the century, MD Chalmers recommended integrating the judicial precedents and further amended the provision of sedition. The intent was to nip any disaffection in the bud. He likened the right of free speech of Indians akin to smoking a cigar near the gunpowder room! Chalmers integrated the Bangabasi, Tilak, and Amba Prasad cases to give a new and notoriously bigger meaning to sedition.

Gestation Phase of Indian Constitution

The Government of India Act of 1935 created a Federal Court for India, which had appellate jurisdiction over all high and lower courts of India. In 1942, in the Narendra Dutt case, the Federal Court set a precedent and limited sedition to ‘incitement of public disorder’. It was overturned in Sadashiv Narayan Bhalerao, as the Privy Council found mere incitement of the feeling of enmity towards the government sufficient to launch a trial. The Council’s decision would culminate in providing fodder to revive sedition in India, supplemented by the restrictions on Fundamental Rights.

The Constituent Assembly has often been criticised for lacking universal adult franchise, and allowing a meagre representation of those who fought to forge an anti-imperialist sentiment. The ones who first proposed the idea of a Constituent Assembly in India, the communists, were left out barring Somnath Lahiri, a communist and trade unionist from Bengal, who would relentlessly fight for the rights of workers. He proposed an amendment to redact the sedition law and was member of the Constituent Assembly for a brief period. On the debate about restrictions on liberties, an irate Lahiri said, ‘‘Many fundamental rights have been framed from the point of view of a police constable’’. He remarked on the shallowness of rights and liberties since all were followed by a proviso restricting them with ambiguous wordplay.

After an incessant discussion on the nature of free speech in India, in the last hours of the Constituent Assembly, Dr BR Ambedkar seconded the opinion of KM Munshi to remove sedition as a restriction over free speech. Hence, on the day India became a republican democracy, the Constitution did not have the baggage of sedition on its back.

Sedition in Constitutional Democracy

The Constituent Assembly removed sedition from the provisos listing restrictions to liberty, but the sedition law was not obsolete. Parliament had not repealed the provision from the penal statute. In the Romesh Thappar and Brij Bhushan cases, the judiciary actualised the liberty to express, but in a new democracy, many were apprehensive of the expansive nature of freedom of speech. For instance, Vallabhbhai Patel wrote to Jawaharlal Nehru pointing out that allowing criticism as a form of public accountability, while recognising extreme cases where national security is at risk, may make limitations on freedom of the press necessary.

Similarly, Justice Sarjoo Prasad noted in the Shailabala Devi verdict, “I cannot with equanimity contemplate such an anomalous situation, but the conclusion appears to be unavoidable on the authority of the Supreme Court judgement with which we are bound.” The apprehension would soon mould the stream of liberties as the First Constitutional Amendment would introduce three new restrictions to limit free speech. This overturned the precedents set by the apex court in matters about free speech.

Lahiri’s speech in the Constituent Assembly lodged his apprehensions of the “meagre fundamental rights” being whittled down on the convenience of the executive. This came to pass in 1962 when the firebrand communist leader Kedar Nath Singh was convicted of sedition, the first such conviction in independent India. Later, its application became subject to blatant abuse by the executive. Alva throws light on Nehru’s speech in Parliament wherein he castigated sedition as highly “objectionable” and “obnoxious”, and that the provision of public order had no relevance. The Allahabad High Court in the Ram Nandan case relied on Nehru’s speech in Parliament and held sedition was not part of public order. (Although the apex court revived sedition in Kedar Nath Singh under the pretext of the ‘public order’ restriction inserted in Article 19(2).) The court not only erred in interpreting public order and public disorder but “donned the hat of the legislator” and made sedition consistent with a restriction which was neither the will of Parliament nor compatible with free speech. Moreover, the bench unconventionally overturned the Romesh Thappar precedent of a larger bench.

Unfortunately, the Indian executive failed to walk the talk. In 1963, the 16th Constitutional Amendment inserted a new restriction to freedom of speech and expression, namely, sovereignty and integrity. It led to the enactment of the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act or UAPA in 1967. At the beginning of the 21st century, the draconian law became even more lethal as the amendment equipped the law to deal with “terrorist activity”, but it was loosely defined. The UAPA bill of 2019 reincarnated the Rowlatt Act after a century where an individual could simply be labelled a terrorist.

Though the apex court, while dealing with the constitutionality of sedition, only deals with how it features in penal statutes, it has halted the use of the provision. It has said, “All pending trials, appeals and proceedings with respect to the charge framed under Section 124A of the IPC be kept in abeyance.” Abeyance, however, does not fetch the desired results for Alva. He argues that the current trial is a roadmap to a “pyrrhic victory”, since repealing the sedition provision would be insufficient as it would remain operative under the UAPA (under section 2(1)(o)(iii)).

Alva makes a compelling case to repeal the provision of sedition from the Indian statutes. The book has many well-cultivated minute details. It offers a descriptive history of sedition and is pertinent considering the attacks on journalists, academicians and activists. A report published by the World Press Freedom Index paints a dismal picture, saying press freedom has plummeted over the years in India, from the 133rd rank in 2016 to 161st in 2023. Similarly, the United Kingdom-based, Business and Human Rights Resource Centre puts India at the top of the list, after Brazil, for its pernicious outlook towards activists in 2022. With around 54 attacks on activists, the report suggests the attacks are often State-backed.

The Supreme Court recently said the Constitution is a tradition breaker. How far it has gone to break the tradition of silencing critical voices is yet to be seen. As several third-world ex-British colonies have removed sedition from their statutes, India too must wake up for its promised tryst with destiny.

The author is a lawyer practising in Delhi. The views are personal.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.