From Telstar 18 to Boots and Jerseys, the Plastic Side of FIFA World Cup

(From left) Alessandro del Piero, Lukas Podolski, Zinedine Zidane, Kaka and Xabi Alonso during the launch of the 2018 FIFA World Cup match ball -- Telstar 18 -- in Moscow last year. Photo Credit: FIFA

You don’t need plastics in sumo wrestling, perhaps, but then again, one can’t be too sure these days. Try and think of any sport that can survive without it. Think of the racquet Bjorn Borg used at Roland Garros. Now, think of the one Rafael Nadal uses to win the French Open. 10-0 in favour of plastics.

Despite this, it’s intriguing that well into the 20th century, children were still using inflated bladders of pigs for a kickabout in the park. Before plastics, professional footballs consisted of an inflatable rubber bladder, a cotton lining and a stitched leather cover. Despite the rules regarding the quality and dimension of the balls, in FIFA’s regularly revised Laws of the Game, it wasn’t uncommon to see the ball used for World Cups were tailored to the home team’s advantage (a reason, why at the first ever FIFA World Cup, the two finalists insisted on playing a half each with their own ball).

Those times, though, are long gone. The football used in the World Cup isn’t just a piece of equipment used to determine football matches anymore, it is a marketing ploy, a branding exercise in capitalist excess.

Every ball is better despite being in essence the same. Since 1970, Adidas have been responsible for manufacturing the official World Cup ball. Each ball, has a name, and a unique moment inscribed to it. And each one is controversial, mostly for footballing reasons.

READ MORE | 10 Tales of Intrigue From the First FIFA World Cup

Consider the Adidas ball of the 2010 FIFA World Cup -- the Jabulani. Developed by engineers and scientists at Loughborough University, the UK, the construction of the ball comprised eight 3D spherically moulded panels which were thermally bonded together. These panels were made of EVA and TPU, moulded together to deliver a perfectly round shape. The unique ‘Grip ’n’ Groove’ profile of the ball ensured stable flight and a perfect grip in any weather condition. All of this were made possible, because of plastic.

However, the Jabulani had a problem. It was too perfect. Goalkeepers were left flummoxed by its trajectory through the World Cup. None of this, though, affected Diego Forlan, the true master of the Jabulani.

PLASTIC SPORT

It is impossible now, to think of football minus the plastic… or any sport for that matter. Let us, for the moment forget about the ball and instead move on to footwear. Football boots (or for that matter any athletic footwear) is all about being light. The UK-based company, Zotefoams, could never have developed the world’s lightest footwear without plastics. It developed a special foam for midsoles and insoles for trainers and football boots which was five times lighter than EVA foam, and with higher temperature resistance. Now athletes can run faster due to the better energy return from the shoe they are sprinting in.

Plastics have liberated sports equipment design. The craft and oars used in rowing have progressed from wood to plastic composites. Rocky Balboa won’t be jabbing dead cow carcasses. Think, instead, Nylon and polyster mesh bags, filled with sand or foam.

Even clothing has changed. Go back to the time the centre back used to tear the T-shirt off the centre-forward running with the ball. That is no longer possible. The modern (made with plastics) sportswear is waterproof and can be designed to minimise the wind resistance of an athlete’s body. They can also be easily coloured and decorated to help ease recognition for spectators and officials.

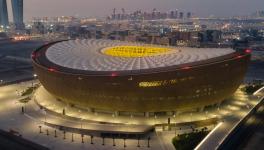

This, of course, is another great marketing opportunity. Teams now conveniently make kits out of recycled plastic waste. But that simply that isn’t enough. Plastic products facilitate the safe enjoyment of major sporting events. Comfortable, ergonomically optimal seats, to hold, say, the swinging 60,000 football fans. An overarching roof to save spectators from the elements. Drinks and meals at half-time, or tea break on Day 4 of a cricket match, or at the end of a chukker. Served in plastic.

THE SINGLE USE PROBLEM

Safe to say then, that plastic cannot be eliminated from sporting life. Or from modern life. You are, after all, reading this story on a device made possible only because of plastic.

The easier thing to do then is beat the problem that is beatable -- single-use plastics. Since the late 1970s, single-use plastics have become the vanguard of plastic production. The global growth of the packaging segment of plastic production is proof of this. The emergence of supermarkets, first in the West and then in the Rest, was a primary incentive.

Today, single-use plastics have cling-wrapped and meal-trayed the world. It is now a throwaway pandemic. Less than 1% of all single use plastic items are recycled. They mostly end up either in your nearest landfill, or the nearest ocean—carried by flying street litter into a stormwater drain, dumped into a sewage drain, flowing into a river, or thanks to a picnic last weekend at the beach.

And sporting venues are at the epicenter of this deluge. Ignoring the rising price of the cold drink in a stadium, let us for one moment, step back and order one, and think of what happens next. Straws, plates, wrappers, packets are all part of this problem. And the truth is, eliminating these elements is a very realistic possibility, if the will exists.

Clean ups won’t are no longer a means to resolve the issue of plastic waste. Popular discourse regularly points to behavioral change as the means to achieving a plastics-free end. And yet, it is hard to imagine a less superficial, or less incentivised, solution—and one that puts the pressure for the clean up on the middle classes, for whom an affordable substitute for a plastic bin liner is still pending.

Football leagues in the UK have already been called out to cut the amount of single-use plastics used at stadiums. Mary Creagh, the chair of the Commons Environmental Audit Committee, said deposit return schemes should be introduced at stadiums. And in India, there is no reason for it to be any different.

And here we must digress, of course, because Indian football’s spectator footprint is negligible to the point of being invisible. Cricket rules the roost. And to visit a cricket stadium in the aftermath of an IPL game is like going to a single-use plastics crime scene. Some stadiums have changed stance, but runners remain.

A simple solution, one that requires minimum intervention and maximum behavioral change (from the management, mind) is segregating the waste at the source. Stadiums are enclosed, highly controlled spaces, with little in terms of unscanned input or output. Most plastic waste from the stadiums, though is generally clubbed together with trash and thrown towards the garbage pile. Smarter management will ensure that all plastic waste from stadiums is directed towards plastic recycling facilities. Imagine the revenue you will give them. One IPL season can probably buy a few condos.

Otherwise, simple things, throwbacks to a simpler time, can make everything go away. It can be the start towards a cleaner future. Allow, people to carry their own water for games. Granted, there will be the occasional vodka sneaked in but a few unruly fans are worth the price of an unplastified albatross. Substitute plastic plates and glasses with more sustainable alternatives. And this, for companies which rake in millions, is a small blip to pay. Encourage reuse, for returning customers. And, for god’s sake, do away with those plastic cheer sticks and ‘sixer’ signs.

Rarely does the phrase turn the clock back, really mean something. In this case, it could. Hashtags influence policy makers more than screamed demands. And so, here’s one to pay heed to. #DontBeAPlasticFan

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.