The Tilted Global Scales: Tax Havens and Financial Secrecy

The new Panama leaks have once again provided a fleeting glimpse into the world of finance capitalism. These newly obtained documents display how Mossack Fonseca went into damage control mode and scaled down their operations following the first leak in 2016. Several important names have been revealed through the new leaks such as Ajay Bijli of PVR Cinemas, Kavin Bharti Mittal, the son of Airtel's Sunil Mittal and Jalaj Ashwin Dani, son of Asian Paints promoter Ashwin Dani. Therefore, once again the issue of 'tax havens' comes to the fore.

Read More: New Panama Paper Leak Finds 12,000 Indians Guilty of Illegal Offshore Dealings

Tax havens generally fall within two categories; no-tax jurisdictions, or low-tax jurisdictions. The no-tax jurisdictions are not actually devoid of taxes but are jurisdictions which do not levy certain taxes. The same goes for low-tax jurisdictions which levy relatively low taxes on certain financial flows. What policies a country frames within its own borders is its own business, provided of course that the policies do not violate the country's international commitments. The problem, however, arises in a globalised world economy. One common practice that emerged was offshoring. Companies from the developed world relocated their manufacturing to the not so developed world where the minimum wage was lower, and so were the taxes. This process was further supported by the portrayal of Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) as the panacea to lift poor countries out of poverty.

The over-reliance on FDI as a get-rich-quick scheme inevitably led to certain phenomena such as the creation of Special Economic Zones (SEZ) as well as in more serious cases, countries signing away their sovereignty to financially powerful multinational corporations. One example of the latter is Zambia where the people living in poverty is anywhere between 60 to 80 percent of the population. This is despite the country being the 8th largest producer of copper. However, the major players in Zambia's mining industry are all multinational entities; the Canadian firm Barrick, the Canadian firm FQM, the UK firm Vedanta, the Swiss firm Glencore and China’s Non-Ferrous Metals Mining Corporation. It is evident that in this case, FDI is not helping anyone except the corporations and their local lackeys in the industry and the government.

Read More: As Mining Companies in Africa Make Billions, Children Are Left Illiterate

The case of Zambia is not always what every country is faced with. For more financially sound countries the issues posed by the globalised financial order arise in the form round-tripping. For example, in India, investments from Singapore and Mauritius are exempt from capital gains tax among other taxes. Both these countries are known tax havens. Further, data on foreign investment in India shows that the source of 50 per cent of the FDI that comes into India are from both these countries. In the financial year 2016 -17, India received FDI worth about Rs. 3 lakh crores. Out of this, Rs. 1.6 lakh crore came from Singapore and Mauritius. The Foreign Portfolio Investments (FPI) from these two tax havens amounts to around Rs. 8 lakh crore. This quantum of investment need not necessarily be considered the product of round-tripping money from India. However, considering the revelations in the 2G Cases – where a significant number of companies implicated were set up by Indians in Mauritius – one may safely presume that a significant portion of the investment may be actually round-tripped money. Incidentally, neither Singapore nor Mauritius is mentioned in the European Union's (EU) list of non-cooperative tax jurisdictions.

Read More: India Tripping on Black Money in Tax Havens

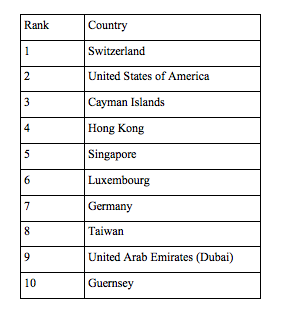

The EU's list contains seventeen countries and territories. The more financially powerful ones are; Macao SAR, the United Arab Emirates, and the Republic of Korea. While not so powerful ones on the list were the Marshall Islands, Palau and Samoa. The list includes those countries that are identified as non-cooperative regarding tax disclosures. However, the Tax Justice Network (TJN) does not frame the problem as that of 'tax haven' jurisdictions, but instead, the issue is financial secrecy. This arises since countries are always willing to attract cash inflows, irrespective of whether the money consists of the proceeds of a crime or not. Therefore, such a policy is detrimental not only if the money flowing in is round-tripped, but also to other countries where a crime may have occurred. The TJN's Financial Secrecy Index ranks countries on the level of financial secrecy they provide weighted by their share in international finance.

It should not come as a surprise that Switzerland tops the list of financial secrecy. The country has long been lambasted as the destination of 'black money'. This thought has become public knowledge after the HSBC leaks in 2008. What may surprise some is that the United States of America (USA) occupies the second position. The USA however, has several tax havens within its borders – such as Delaware and Florida – which may have affected its ranking. One of the major contributors of foreign investment in India, Singapore, is ranked at the fifth position. While only the United Arab Emirates features in the top ten from the EU's list. Among the top ten financially secretive countries, two are the sources of famous 'leaks' (Switzerland and Luxembourg).

Read More: Carving up a Business Empire Through Tax Havens: The Ambani Way

When one considers the Global Financial Integrity's (GFI) report on financial flows and tax havens, the image conjured particularly for the developing world is not positive. The report which was published in 2016 compared available data on balance of payments among other indicators from countries across the world. The report found that residents of developing countries held USD 4.4 trillion in tax havens in 2011. Another report which analysed illicit financial outflows from developing countries found that in 2014 illicit outflows ranged from USD 620 billion to 920 billion, while inflows ranged from USD 1.4 trillion to 2.5 trillion. What the higher volume of capital inflows could indicate here is that money laundering is taking place. On one hand local elites could be round-tripping money and on the other hand, foreign capital could also be laundered inside the country's jurisdiction.

What this represents is that untaxed wealth survives due to tax havens and financially secretive policies. It is not the people with small holding who are capable of hiding away their wealth from the tax authorities – unless they bury it or stuff it under a mattress. It is the big players who are capable of jet-setting across the world, hiring international attorneys, and conjuring complicated shareholdings who are the most likely offenders. However, considering that in most countries it is this class of people who are connected to the government if not in the government, it is unlikely that much headway can be made unless a broad-based international agreement is framed.

Get the latest reports & analysis with people's perspective on Protests, movements & deep analytical videos, discussions of the current affairs in your Telegram app. Subscribe to NewsClick's Telegram channel & get Real-Time updates on stories, as they get published on our website.